Category: Recommended Reading

Stealing Pushkin

Rachel Donadio at the NYT:

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

Four months later, during a routine annual inventory, the library discovered that eight books the men had consulted had disappeared, replaced with facsimiles of such high quality that only expert eyes could detect them. “It was terrible,” Krista Aru, the director of the library, said. “They had a very good story.” At first, it seemed like a one-off — bad luck at a provincial library. It wasn’t. Police are now investigating what they believe is a vast, coordinated series of thefts of rare 19th-century Russian books — primarily first and early editions of Pushkin — from libraries across Europe.

more here.

Trump Inc. on trial

Marie Morelli in Syracuse.com:

Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid.

Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid.

Trump and other defendants are accused of duping banks, insurers and others by inflating his wealth on financial statements. The ex-president’s children Ivanka and Donald Jr. also testified, provoking visual barbs from Jack Ohman and Drew Sheneman. Mike Luckovich draws Trump in an overvalued prison cell. Sheneman has him overseeing an overpriced garage sale.

More here.

Taylor Swift Is Doing Michael Jackson–Level Numbers, but Does She Have a “Billie Jean”?

Chris Molanphy in Slate:

Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100?

Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100?

I know, I know … it’s a little hard to keep up with her relentless output. If you are among the Americans only passively aware of Swift’s oeuvre, you might think her last No. 1 was the moody one where she says hi, she’s the problem, it’s her. But “Anti-Hero” hit No. 1 nearly 18 months ago. What about that percolating bop about the hottest days of the year? Improbably, “Cruel Summer” reached No. 1 last fall—not only late for summer, but four years after its original release as a Lover album cut. But nope, there was another new Taylor No. 1 after that.

…In short, you don’t need me to tell you why this song is No. 1. It’s obvious. What none of us can answer is whether “Fortnight” will be remembered as a classic Taylor hit or a side effect of Swift’s biggest album launch ever, the moment when she beat her own record by sweeping the Top 14 slots on the Hot 100. Other first singles from prior Swift LPs, like “Look What You Made Me Do,” “Cardigan,” and “Willow” made big Hot 100 splashes but fell off quickly and never became lasting radio hits. Will “Fortnight” go down as an “Anti-Hero,” an “Is It Over Now?,” or a “Look What You Made Me Do”? Could it maybe even be Taylor Swift’s “Billie Jean”?

More here.

Saturday Poem

………….

Letter l as in

Reliable, Indomitable, Chivalrous

……… For Loraine Lins

It’s hard not to like

……………………… l. Life

………….. Love. Luck. It’ so full

of lofty ideals. A natural born leader

………………………of all the laggard………….

………….. vowels, lugubrious u,

ever loitering e. loopy o.

………………………Think, l seems to say,

………….. of all you can accomplish

if you work at it as diligently

……………………….as an adverb.

………….. It latches on

to an adjective and sweetly

……………………….softly, almost indiscernibly,

………….. persuades it to

spread its goodwill to the rest

………………………of the sentence.

………….. Lambent. Luminous.

Lucent. What pleasure there is

……………………….in working certain words

………….. into sentences. l. changes

everything. Unflinching—

……………………….ly, unstintingly, it labors,

………….. Let the earth

put forth vegetation, plants

……………………….yielding seed, and fruit trees

…………… fruit in which is their seed.

That’s not just the Lord

………………………talking. That’s

………….. language. Let there be . . .

How lovely it feels

……………………….to tuck the tongue

………….. against the teeth

and let the lungs do the rest.

by Christopher Bursk

from The First Inhabitants of Arcadia

University of Arkansas Press, 2006

Friday, May 3, 2024

Yan Lianke Wants You to Stop Describing Him As China’s Most Censored Author

Yan Lianke at Literary Hub:

In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it.

In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it.

Authors should be very clear that being banned is not synonymous with artistic success. Sometimes, being banned is equated with courageousness, and we can certainly understand Goethe’s observation that without courage, there would be no art. If we were to extend this logic, we could even say that without courage, there would be no artistic creation. However, many readers view censorship and controversy only at the level of courage—particularly in relation to authors from China, the former Soviet Union, and other so-called third-world countries.

More here.

Mother trees and socialist forests: is the ‘wood-wide web’ a fantasy?

Daniel Immerwahr in The Guardian:

The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but intelligent subjects. Trees have thoughts and desires, Wohlleben writes, and they converse via fungi that connect their roots “like fibre-optic internet cables”. The same idea pervades The Overstory, Richard Powers’ celebrated 2018 novel, in which a forest scientist upends her field by demonstrating that fungal connections “link trees into gigantic, smart communities”.

The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but intelligent subjects. Trees have thoughts and desires, Wohlleben writes, and they converse via fungi that connect their roots “like fibre-optic internet cables”. The same idea pervades The Overstory, Richard Powers’ celebrated 2018 novel, in which a forest scientist upends her field by demonstrating that fungal connections “link trees into gigantic, smart communities”.

Both books share an unlikely source. In 1997, a young Canadian forest ecologist named Suzanne Simard (the model for Powers’ character) published with five co-authors a study in Nature describing resources passing between trees, apparently via fungi. Trees don’t just supply sugars to each other, Simard has further argued; they can also transmit distress signals, and they shunt resources to neighbours in need. “We used to believe that trees competed with each other,” explains a football coach on the US hit television show Ted Lasso. But thanks to “Suzanne Simard’s fieldwork”, he continues, “we now realise that the forest is a socialist community”.

The idea of trees as intelligent and cooperative has moved swiftly from research articles to “did you know?” cocktail chatter to children’s book fare.

More here.

Sean Carroll and Brian Greene: Does Quantum Mechanics Imply Multiple Universes?

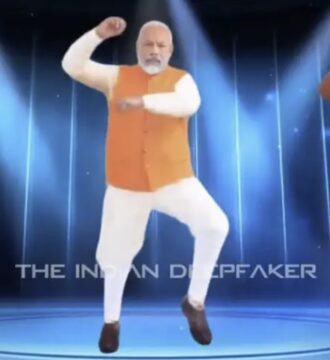

Deepfake politicians may have a big influence on India’s elections

Jeremy Hsu in New Scientist:

Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of AI-generated deepfakes.

Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of AI-generated deepfakes.

India’s nearly 970 million eligible voters started going to the polls on 19 April in a multi-phase process lasting until 1 June that will select the next government and prime minister. It has meant booming business for Divyendra Singh Jadoun, whose company The Indian Deepfaker typically uses AI techniques to create special effects for ad campaigns and Netflix productions.

His firm is handling more than a dozen election-related projects, including creating holographic avatars of politicians, using audio cloning and video deepfakes to enable personalised messaging en masse, and deploying a conversational AI agent that identifies itself as AI, but speaks in the voice of a political candidate during calls with voters.

More here.

Diseases of Civilization: Are Seed Oil Excesses the Unifying Mechanism?

I like Eyck

Gregory T. Clark at The New Criterion:

Over the course of the thirty years that I taught art history to college undergraduates, introducing my students to the manuscript illuminations and panel paintings of the fifteenth-century Flemish painter Jan van Eyck always gave me an especial pleasure. I wanted my students to share in my wonderment at Jan’s seemingly effortless ability to present nature rather than represent it, right down to the most infinitesimal details, without compromising the integrity of the whole, his powers of observation complemented by an uncanny ability to capture light, texture, and atmosphere.

Over the course of the thirty years that I taught art history to college undergraduates, introducing my students to the manuscript illuminations and panel paintings of the fifteenth-century Flemish painter Jan van Eyck always gave me an especial pleasure. I wanted my students to share in my wonderment at Jan’s seemingly effortless ability to present nature rather than represent it, right down to the most infinitesimal details, without compromising the integrity of the whole, his powers of observation complemented by an uncanny ability to capture light, texture, and atmosphere.

The earliest surviving works of Jan—who is thought to have been born around 1390 in Maaseyck, modern-day Belgium—date to the first lustrum of the 1420s. In 1425, he was appointed court painter to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, whose empire then comprised almost the entirety of the Low Countries and a large wedge of northeastern France together with his home duchy of Burgundy and the contiguous Franche-Comté (Free County) to the east.

more here.

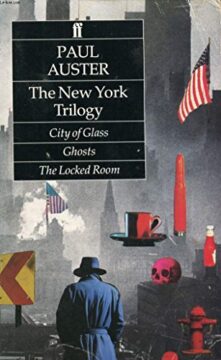

Paul Auster’s Literary Legacy (1947 – 2024)

Erica Wagner at the New Statesman:

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature.

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature.

City of Glass, in which a writer of detective fiction is pulled both into and away from “the real world”, or the world at least as he has perceived it, reads like a mystery, but the real mystery at its heart is one of identity and the role that chance plays in all our lives. These issues would echo throughout Auster’s work, in novels such as Moon Palace (1989), The Music of Chance (1990) and The Book of Illusions (2002).

more here.

Paul Auster Reads

Art Isn’t Supposed to Make You Comfortable

Jen Silverman in The New York Times:

When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators.

When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators.

When I say “humanity” I mean their confusion, self-justifications and willingness to lie to themselves. Atrocity doesn’t just come out of evil, Endo was saying, it emerges from self-interest, timidity, apathy and the desire for status. His novel showed me how, in the right crucible of social pressures, I, too, might delude myself into making a choice from which an atrocity results. Perhaps this is why the book has haunted me for nearly two decades, such that I’ve read it multiple times.

More here.

Friday Poem

Honeymoon Flight

Below, the patchwork earth, dark hems of hedge,

The long grey tapes of road that bind and loose

Villages and fields in casual marriages:

We bank above the small lough and farmhouse

And the sure green world goes topsy-turvy

As we climb out of our familiar landscape.

The engine noises change. You look at me.

The coastline slips away behind the wing-tip.

And launched right off the earth by force of fire,

We hang, miraculous, above the water,

Dependent upon the invisible air

To keep us airborne and to bring us further.

Ahead of us the sky’s a geyser now.

A calm voice talks of cloud yet we feel lost.

Air-pockets jolt our fears and down we go.

Travellers, at this point, can only trust.

by Seamus Heaney

from Death of a Naturalist

Faber and Faber, 1966

Thursday, May 2, 2024

The Real Scandal of Campus Protest

Erik Baker in the Boston Review:

One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it.

One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it.

More here.

AI that determines risk of death helps save lives in hospital trial

Jeremy Hsu in New Scientist:

An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent.

An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent.

“This is actually quite extraordinary,” says Eric Topol at the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California, who was not involved in the research. “It’s very rare for any medication to [produce] a 31 per cent reduction in mortality, and then even more rare for a non-drug – this is just monitoring people with AI.”

More here.

Daniel Dennett: The 4 biggest ideas in philosophy

The Moloch Trap of Environmental Problems

Hannah Ritchie at Sustainability By Numbers:

A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

It explains the situations with externalities or the preference for short-term gains at the sacrifice of the long-term future.

The problem is that it’s incredibly hard for any “player” to break the trap. If they do, they will lose out in the short term (and they might still be exposed to the downsides in the long term). Everyone is stuck in a “game” or “race” that they don’t want to be in, but it’s impossible to stop.

More here.