Sam Adler-Bell in The Baffler:

THERE’S A GAME my girlfriend and I sometimes play. Well, really, it’s more of an argument: “Fuck, Marry, Kill” with the past, present, and future. My answer, which I take to be a good, solid American answer, is fuck the present, marry the future, and kill the past. My reasoning is that you should always want to fuck the present, to live in the moment (as the advertisers say), screw every hole of the now. Likewise, marrying the future is admirable, like monogamy, and prudent, like monogamy; it’s a wish, and a promise, for stability and grace. You have to believe in the future, be loyal to what comes next, to what and who you are always becoming. And that leaves only the past to kill. Which, so what? It’s the past. It’s already passed.

My girlfriend—who is also an American, but an American writer and lover of fiction—has a different answer. She says you should fuck the future, marry the past, and kill the present. I definitely see the appeal of fucking the future; it’s where the action is, the excitement, the unknown. The future is a stranger, and we all want to fuck strangers. And for her, the past is too precious and monumental to kill. Memory is a repository, a treasured burden worth bearing; it’s what you can’t seem to get rid of, even if sometimes you want to. So, you marry it. But here’s where the trouble starts: I can’t allow her to kill the present. When we get going on this topic, she says, “Well, what’s the present? Isn’t it always slipping away? Isn’t it gone the moment you try to do something in it?” And I say, “No! The present is this,” slicing my hand through the air, as if to catch it. “Isn’t this precious?”

More here.

The tails were a clue. As some kinds of mice get old, their tails can stiffen and kink. But the aged rodents in the lab of molecular biologist Shin-Ichiro Imai at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis sported tails that were limber and nearly straight. The genetically altered mice seemed to defy aging in other ways, too. They were more robust than control mice and spent more time scampering in their exercise wheels. Most dramatic,

The tails were a clue. As some kinds of mice get old, their tails can stiffen and kink. But the aged rodents in the lab of molecular biologist Shin-Ichiro Imai at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis sported tails that were limber and nearly straight. The genetically altered mice seemed to defy aging in other ways, too. They were more robust than control mice and spent more time scampering in their exercise wheels. Most dramatic,  Despite Steve Bannon’s Wall Street pedigree, his taste for

Despite Steve Bannon’s Wall Street pedigree, his taste for  O

O In his novella “The Prague Orgy,” Philip Roth has a Czech writer say: “When I studied Kafka, the fate of his books in the hands of the Kafkologists seemed to me to be more grotesque than the fate of Josef K.” Just as Franz Kafka’s prose both demands and evades interpretation, something about his legacy has both solicited and resisted claims of ownership.

In his novella “The Prague Orgy,” Philip Roth has a Czech writer say: “When I studied Kafka, the fate of his books in the hands of the Kafkologists seemed to me to be more grotesque than the fate of Josef K.” Just as Franz Kafka’s prose both demands and evades interpretation, something about his legacy has both solicited and resisted claims of ownership. There’s been renewed debate around Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education recently, so I want to discuss one way I think about this question.

There’s been renewed debate around Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education recently, so I want to discuss one way I think about this question. I

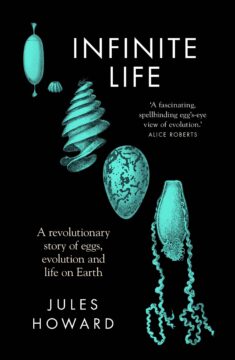

I Jules Howard is no stranger to sex. A science writer and zoological correspondent, his gleefully amusing 2014 book

Jules Howard is no stranger to sex. A science writer and zoological correspondent, his gleefully amusing 2014 book  A

A The quantum revolution in physics played out over a period of

The quantum revolution in physics played out over a period of  In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come.

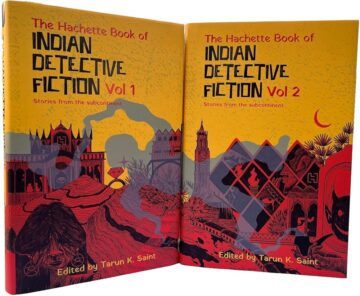

In the early fifth century BC, the Olympic boxer Kleomedes was disqualified from a match after killing his opponent with a foul move. Outraged at being deprived of the victory and its attendant prize, he became “mad with grief” and tore down a school in his hometown, killing many of the children who were studying there. Kleomedes managed to escape the angry mob that soon pursued him, and disappeared without trace. When the community sought answers from the oracle at Delphi, they were told that Kleomedes was now a hero, and should be honored accordingly with sacrifices. This the people did, and continued to do for centuries to come. Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story.

Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story. The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘

The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘