UPDATE 3/19/12: The winners have been announced here.

UPDATE 3/8/12: The finalists have been announced here.

UPDATE 3/7/12: The semifinalists have been announced here.

UPDATE 2/29/12: Voting round now open. Click here to see full list of nominees and vote.

Dear Readers, Writers, Bloggers,

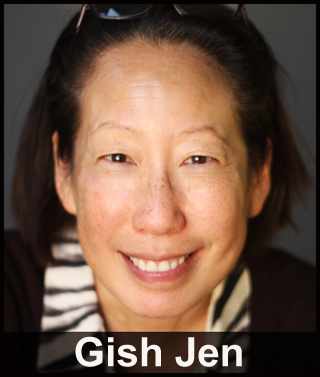

We are very honored and pleased to announce that Gish Jen has agreed to be the final judge for our 3rd annual prize for the best blog and online writing in the category of arts and literature. (Details of the inaugural prize, judged by Robert Pinsky, can be found here, and more about last year's prize, judged by Laila Lalami can be found here.)

We are very honored and pleased to announce that Gish Jen has agreed to be the final judge for our 3rd annual prize for the best blog and online writing in the category of arts and literature. (Details of the inaugural prize, judged by Robert Pinsky, can be found here, and more about last year's prize, judged by Laila Lalami can be found here.)

Gish Jen is a novelist. Her first novel, Typical American, was a finalist for the National Book Critics' Circle award, and her second novel, Mona in the Promised Land, was listed as one of the ten best books of the year by the Los Angeles Times. Her latest novel, World and Town, won the 2011 Massachusetts Book Prize and has been nominated for the 2012 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Her short work has appeared in numerous periodicals including The New Yorker, the Atlantic, the Paris Review, Daedalus, the New Republic, and The New York Times. She has also been included in dozens of textbooks and anthologies, including several Best American Short Stories collections, including The Best American Short Stories of the Century, edited by John Updike. The recipient of grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and the National Endowment for the Arts, she also received a Lannan Literary Award for Fiction in 1999, and a $250,000 Strauss Living Award from The American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2003.

Jen has been featured in a PBS American Masters program on the American Novel and was named a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2009. She is slated to deliver the Massey Lectures in American Civilization at Harvard University in the spring of 2012. Her website is www.gishjen.com.

As usual, this is the way it will work: the nominating period is now open, and will end at 11:59 pm EST on February 28, 2012. There will then be a round of voting by our readers which will narrow down the entries to the top twenty semi-finalists. After this, we will take these top twenty voted-for nominees, and the four main editors of 3 Quarks Daily (Abbas Raza, Robin Varghese, Morgan Meis, and Azra Raza) will select six finalists from these, plus they may also add up to three wildcard entries of their own choosing. The three winners will be chosen from these by Gish Jen.

The first place award, called the “Top Quark,” will include a cash prize of one thousand dollars; the second place prize, the “Strange Quark,” will include a cash prize of three hundred dollars; and the third place winner will get the honor of winning the “Charm Quark,” along with a two hundred dollar prize.

(Welcome to those coming here for the first time. Learn more about who we are and what we do here, and do check out the full site here. Bookmark us and come back regularly, or sign up for the RSS feed.)

Details:

The winners of this prize will be announced on March 19, 2012. Here's the schedule:

The winners of this prize will be announced on March 19, 2012. Here's the schedule:

February 20, 2012:

- The nominations are opened. Please nominate your favorite blog entry by placing the URL for the blog post (the permalink) in the comments section of this post. You may also add a brief comment describing the entry and saying why you think it should win. (Do NOT nominate a whole blog, just one individual blog post.)

- We will accept poems and fiction, as well as book or art reviews, criticism, and other types of writing about arts or literature.

- Blog posts longer than 4,000 words are strongly discouraged, but we might make an exception if there is something truly extraordinary.

- Each person can only nominate one blog post.

- Entries must be in English.

- The editors of 3QD reserve the right to reject entries that we feel are not appropriate.

- The blog entry may not be more than a year old. In other words, it must have been written after February 19, 2011.

- You may also nominate your own entry from your own or a group blog (and we encourage you to).

- Guest columnists at 3 Quarks Daily are also eligible to be nominated, and may also nominate themselves if they wish.

- Nominations are limited to the first 200 entries.

- Prize money must be claimed within a month of the announcement of winners.

February 28, 2012

- The nominating process will end at 11:59 PM (NYC time) of this date.

- The public voting will be opened soon afterwards.

March 6, 2012

- Public voting ends at 11:59 PM (NYC time).

March 19, 2012

- The winners are announced.

One Final and Important Request

If you have a blog or website, please help us spread the word about our prizes by linking to this post. Otherwise, post a link on your Facebook profile, Tweet it, or just email your friends and tell them about it! I really look forward to reading some very good material, and think this should be a lot of fun for all of us.

Best of luck and thanks for your attention!

Yours,

Abbas

PALO ALTO, Calif. — This can't be the right place.You would expect the home of Condoleezza Rice— the most successful African-American woman in the history of the executive branch — to be festooned with mementos from her tenure under two Bush presidencies, which culminated in her role as secretary of State.Perhaps some photos with world leaders. Ornate gifts from political counterparts. Lavish furnishings.Nope. Instead, the decidedly generic condo reserved for Stanford University faculty is filled with antiques that belonged to Rice's parents, sports memorabilia and a prominent photograph of her with … cellist Yo-Yo Ma. The only sign of George W. Bush is found on a hockey-puck-size Lucite disc, which is inscribed with a 9/11-era quote from the 43rd president.But make no mistake: There is no distancing going on. Rice is as proud of her record as ever.”I look back on those eight years fondly,” she says, dressed in black, sitting in a small den decorated with NFL helmets and framed shots of her with golfers Ernie Els and Phil Mickelson.”I'm glad I got to serve in a time of tremendous consequence,” says Rice, 55. “We did some things well. Some things not so well. But I'm a big believer that history has a long arc. We'll have final determination on things we did long after I'm gone. And that's fine.”A change in direction Rice set out to dissect her political life in a book, but that was put on hold when she opted to first pay tribute to the people who truly shaped her, Birmingham, Ala., educators John and Angelena Rice. The result is Extraordinary, Ordinary People: A Memoir of Family.