Darryl Pinckney in The Paris Review:

Jamaica Kincaid was born Elaine Potter Richardson on Antigua in 1949. When she was sixteen, her family interrupted her education, sending her to work as a nanny in New York. In time, she put herself on another path. She went from the New School in Manhattan to Franconia College in New Hampshire, and worked at Magnum Photos and at the teen magazine Ingenue. In the mid-’70s, she began to write for The Village Voice, but it was at The New Yorker, where she became a regular columnist for the Talk of the Town section, that everything changed for her. Her early fiction, much of which also appeared in that magazine, was collected in At the Bottom of the River (1983), a book that, like her Talk stories, announced her themes, her style, the uncanny purity of her prose. She has published the novels Annie John (1985), Lucy (1990), The Autobiography of My Mother (1996), Mr. Potter (2002), and See Now Then (2013). A children’s book, Annie, Gwen, Lilly, Pam and Tulip, came out in 1986. Aside from the collected Talk Stories (2001), her nonfiction works include A Small Place (1988), a reckoning with the colonial legacy on Antigua; My Brother (1997), a memoir of the tragedy of AIDS in her family; and two books on gardening, My Garden (Book) (1999) and Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya (2005).

Jamaica Kincaid was born Elaine Potter Richardson on Antigua in 1949. When she was sixteen, her family interrupted her education, sending her to work as a nanny in New York. In time, she put herself on another path. She went from the New School in Manhattan to Franconia College in New Hampshire, and worked at Magnum Photos and at the teen magazine Ingenue. In the mid-’70s, she began to write for The Village Voice, but it was at The New Yorker, where she became a regular columnist for the Talk of the Town section, that everything changed for her. Her early fiction, much of which also appeared in that magazine, was collected in At the Bottom of the River (1983), a book that, like her Talk stories, announced her themes, her style, the uncanny purity of her prose. She has published the novels Annie John (1985), Lucy (1990), The Autobiography of My Mother (1996), Mr. Potter (2002), and See Now Then (2013). A children’s book, Annie, Gwen, Lilly, Pam and Tulip, came out in 1986. Aside from the collected Talk Stories (2001), her nonfiction works include A Small Place (1988), a reckoning with the colonial legacy on Antigua; My Brother (1997), a memoir of the tragedy of AIDS in her family; and two books on gardening, My Garden (Book) (1999) and Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya (2005).

Kincaid divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she is a professor of African American studies at Harvard University, and Bennington, Vermont, where her large brown clapboard house with yellow window trim is shielded by trees. She has two children from her marriage to the composer Allen Shawn, the son of the former New Yorker editor William Shawn, and in the living room she displays on a table—proudly, apologetically—productions from the arts-and-crafts camps and classes that her son and daughter attended over the years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The United States Constitution is in trouble. After Donald Trump lost the 2020 election, he called for the “

The United States Constitution is in trouble. After Donald Trump lost the 2020 election, he called for the “ Earlier this year

Earlier this year “I

“I Baldwin was 33 in 1957, when he published his short story Sonny’s Blues, and it might be said that the whole of his lifetime went into the story. Readers today coming for the first time to this tale of Harlem life and heroin addiction might view it in contemporary terms, and there’s no harm in that: the messages in the story are as evergreen as the biblical allusions Baldwin uses in the story. But it is also worth recalling that in 1957 there was no Civil Rights Act, the struggle over Jim Crow laws and segregation had a long way to go, and racial conditions and inequalities were deplorable and disregarded by most white Americans. The story poses two brothers’ estrangement over addiction and their ultimate rapprochement as a quietly implicit analogy to racial division and an inspiration toward unity and love, and rides, as its title suggests, on music, specifically jazz. Only a reader with a heart of stone will fail to be moved to tears of recognition, sorrow and joy when the story reaches its conclusion.

Baldwin was 33 in 1957, when he published his short story Sonny’s Blues, and it might be said that the whole of his lifetime went into the story. Readers today coming for the first time to this tale of Harlem life and heroin addiction might view it in contemporary terms, and there’s no harm in that: the messages in the story are as evergreen as the biblical allusions Baldwin uses in the story. But it is also worth recalling that in 1957 there was no Civil Rights Act, the struggle over Jim Crow laws and segregation had a long way to go, and racial conditions and inequalities were deplorable and disregarded by most white Americans. The story poses two brothers’ estrangement over addiction and their ultimate rapprochement as a quietly implicit analogy to racial division and an inspiration toward unity and love, and rides, as its title suggests, on music, specifically jazz. Only a reader with a heart of stone will fail to be moved to tears of recognition, sorrow and joy when the story reaches its conclusion. Like Saul Bellow’s Von Humboldt Fleisher, Hitchens was a “champion detractor,” a terrific hater, and always more fun to read when he was denouncing than when he was praising. Rare is the enemy or ideological foe who gets mentioned in these pages without incurring a quick swat of the pen. Thus, we are treated to “the sinister cretin Reagan,” “that recreational vulpicide Roger Scruton,” “Senator Karl Mundt, a dinosaur Republican and tireless witch-hunter,” “James Jesus Angleton, crazed and criminal head of the CIA,” and so on. Some critics have found such comments silly or bad-mannered. “He was always too ready with abuse,” George Scialabba wrote after Hitchens’s death. I agree, and no doubt being so amused by name-calling is a bad habit, but reading these essays I found it one I was more than happy to indulge.

Like Saul Bellow’s Von Humboldt Fleisher, Hitchens was a “champion detractor,” a terrific hater, and always more fun to read when he was denouncing than when he was praising. Rare is the enemy or ideological foe who gets mentioned in these pages without incurring a quick swat of the pen. Thus, we are treated to “the sinister cretin Reagan,” “that recreational vulpicide Roger Scruton,” “Senator Karl Mundt, a dinosaur Republican and tireless witch-hunter,” “James Jesus Angleton, crazed and criminal head of the CIA,” and so on. Some critics have found such comments silly or bad-mannered. “He was always too ready with abuse,” George Scialabba wrote after Hitchens’s death. I agree, and no doubt being so amused by name-calling is a bad habit, but reading these essays I found it one I was more than happy to indulge. From causing a stir

From causing a stir  Many writers’ graves are

Many writers’ graves are  I

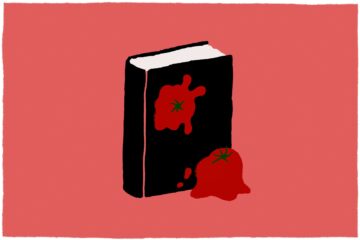

I Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading.

Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading.