Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The Phantoms Haunting History

John Last at Noema Magazine:

Doubts about the accepted chronology of human events are much older than Illig, Velikovsky or Freud. Already by the end of the 17th century, the Jesuit scholars Jean Hardouin and Daniel van Papenbroeck argued that, given the near-ubiquitous practice of forgery in medieval clerical circles, virtually all written records before the 14th century should be considered the invention of overeager monks.

Doubts about the accepted chronology of human events are much older than Illig, Velikovsky or Freud. Already by the end of the 17th century, the Jesuit scholars Jean Hardouin and Daniel van Papenbroeck argued that, given the near-ubiquitous practice of forgery in medieval clerical circles, virtually all written records before the 14th century should be considered the invention of overeager monks.

Two hundred years after Hardouin and van Papenbroeck, the historian Edwin Johnson claimed that the entire Christian tradition — including 700 years of documented history during the so-called “Dark Ages” of Europe — had been the invention of 16th-century Benedictines justifying the privileges of their order. Around the same time, British orientalist Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot was so discouraged by the state of historical records that he proposed the timeline be reset entirely to begin with the accession of Queen Victoria, just 63 years prior.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Early Scenes

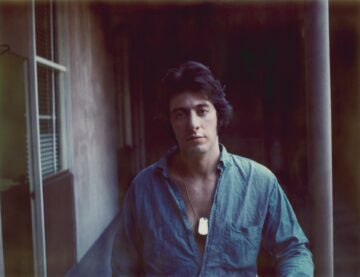

Al Pacino in The New Yorker:

My mother began taking me to the movies when I was a little boy of three or four. She worked at factory and other menial jobs during the day, and when she came home I was the only company she had. Afterward, I’d go through the characters in my head and bring them to life, one by one, in our apartment. The movies were a place where my single mother could hide in the dark and not have to share her Sonny Boy with anyone else. That was her nickname for me. She had picked it up from the popular song by Al Jolson, which she often sang to me.

My mother began taking me to the movies when I was a little boy of three or four. She worked at factory and other menial jobs during the day, and when she came home I was the only company she had. Afterward, I’d go through the characters in my head and bring them to life, one by one, in our apartment. The movies were a place where my single mother could hide in the dark and not have to share her Sonny Boy with anyone else. That was her nickname for me. She had picked it up from the popular song by Al Jolson, which she often sang to me.

When I was born, in 1940, my father, Salvatore Pacino, was all of eighteen, and my mother, Rose Gerardi Pacino, was just a few years older. Suffice it to say that they were young parents, even for the time. I probably hadn’t even turned two when they split up. My mother and I lived in a series of furnished rooms in Harlem and then moved into her parents’ apartment, in the South Bronx. We hardly got any financial support from my father. Eventually, we were allotted five dollars a month by a court, just enough to cover our expenses at my grandparents’ place.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Can the Brain Help Heal a Broken Heart?

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

For decades, researchers have appreciated the intimate association between mental health and physical health, and studies suggest that the mind may impact various bodily systems.1 For example, high levels of stress rendered people more vulnerable to infections; conversely, mental health treatment reduced the risk of rehospitalization by 75 percent in people hospitalized for heart disease.2,3

For decades, researchers have appreciated the intimate association between mental health and physical health, and studies suggest that the mind may impact various bodily systems.1 For example, high levels of stress rendered people more vulnerable to infections; conversely, mental health treatment reduced the risk of rehospitalization by 75 percent in people hospitalized for heart disease.2,3

However, the mechanisms by which mental states might influence the immune or cardiovascular systems are still not well understood. Asya Rolls, a neuroscientist at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, said that these questions are often overlooked because many researchers feel that the field of mind-body connection is not amenable to rigorous scientific exploration. “It’s a major, fundamental gap in our understanding of physiology and medicine, and our ability to help patients,” she said.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I’ve Been

trying all day

to remember that feeling

when you first meet someone

how a match

gets struck

on a rock

how you carry that fire

through each little task

and all day

the people you pass

notice the lights on

notice someone is home.

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

The Ghost Of Donald Judd

Barbara Purcell at Salmagundi:

“A work needs only to be interesting,” Judd continued. And Judd’s work is interesting, even more so in Marfa than, say, MoMA, where a metal box installed in a white cube gallery contained on a city block amidst a vast grid plan makes for a rectilinear set of Russian dolls. The lunar landscape of Far West Texas—the heat and harsh sun and stark outline of emptiness—instead gives these manufactured squares an exotic leg up. At times, Judd’s objects can appear aloof, indifferent. Untitled works give way to a sense of … untitlement. But the desert itself is a poetic reflection of Judd’s aesthetic convictions, where the dominance of negative space enunciates each specific form. This enunciation culminates with the artist’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986, contained in two massive side-by-side artillery sheds at Chinati, a mile from the Block. One hundred pristine boxes—a fingerprint will permanently set in as little as 72 hours—line up on the floor like an army drill. Outwardly identical in size, each one embodies its own internal variations: a tilted top, a hollow center, solid as a rock. No two are the same.

“A work needs only to be interesting,” Judd continued. And Judd’s work is interesting, even more so in Marfa than, say, MoMA, where a metal box installed in a white cube gallery contained on a city block amidst a vast grid plan makes for a rectilinear set of Russian dolls. The lunar landscape of Far West Texas—the heat and harsh sun and stark outline of emptiness—instead gives these manufactured squares an exotic leg up. At times, Judd’s objects can appear aloof, indifferent. Untitled works give way to a sense of … untitlement. But the desert itself is a poetic reflection of Judd’s aesthetic convictions, where the dominance of negative space enunciates each specific form. This enunciation culminates with the artist’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986, contained in two massive side-by-side artillery sheds at Chinati, a mile from the Block. One hundred pristine boxes—a fingerprint will permanently set in as little as 72 hours—line up on the floor like an army drill. Outwardly identical in size, each one embodies its own internal variations: a tilted top, a hollow center, solid as a rock. No two are the same.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Donald Judd

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How to Stop the Future from Destroying Us

Joe Banks in Vice:

Explaining to the uninitiated exactly who Vinay Gupta is, and what he does, isn’t easy.

Explaining to the uninitiated exactly who Vinay Gupta is, and what he does, isn’t easy.

The last time I interviewed him for VICE, nine years ago, the article was headlined ‘The Man Whose Job It Is to Constantly Imagine the Total Collapse of Humanity in Order to Save It.’ Gupta was described as a “software engineer, disaster consultant, global resilience guru, and visionary.” It’s less a career than a vocation—one that reflects a life spent joining together all the scattered dots of where human civilization is now, in order to eliminate the threats that menace its future.

Gupta was part of the original ‘Cypherpunk‘ generation that shaped the utopian early days of the internet in the 1990s. But as well as being a long-established figure in computing, he has a broader history of applying his problem-solving engineer’s mindset to the issues of a sustainable human presence on Earth.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

From Symphony to Structure: Listening to Proteins Fold

Rohini Subrahmanyam in The Scientist:

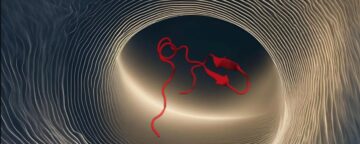

When a protein folds, its string of amino acids wiggles and jiggles through countless conformations before it forms a fully folded, functional protein. This rapid and complex process is hard to visualize.

When a protein folds, its string of amino acids wiggles and jiggles through countless conformations before it forms a fully folded, functional protein. This rapid and complex process is hard to visualize.

Now, Martin Gruebele, a chemist at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, and his team have found a way to use sound along with sight to better understand protein folding. He teamed up with composer and software developer Carla Scaletti, the cofounder of Symbolic Sound Corporation, to convert simulated protein folding data into a series of sounds with different pitches. The scientists identified patterns in the sounds and inferred how the bonds between the amino acids played a major role in orchestrating the folding process. The results, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, will help scientists unravel the mysteries behind protein folding.1

“Vision is one of the most obvious and direct ways to process input, but when you think about it, you use your ears a lot for clues from the environment to get around. You aren’t even often aware of how you use sounds to navigate along with vision,” said Gruebele.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Studying Stones Can Rock Your World

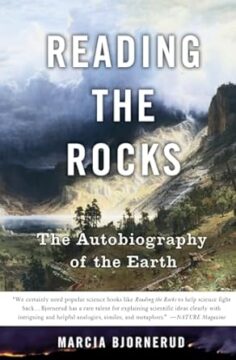

Kathryn Shulz at The New Yorker:

Consider that sandstone, which began, some two billion years ago, as quartz crystals buried deep inside mountains towering over what is now the Upper Midwest and southern Canada. Time took apart the mountains, and rain dissolved most of the minerals in them, but the quartz remained. It was later washed into Precambrian rivers and eventually carried to a beach, where its grains were worn smooth and spherical by the waves. That beach was tropical, partly because the contemporaneous climate was extremely warm, but also because Wisconsin, at the time, was near the equator. As the sea retreated and other rocks and minerals were deposited on top of the former strand, the grains of quartz hardened into sandstone, which was gradually sculpted by wind, water, and glacier until, aboveground, it formed the topography of Wisconsin as we know it today. Belowground, it formed an excellent aquifer, thanks to those spherical grains, which—“like marbles in a jar,” as Bjornerud puts it—leave plenty of room for storing water in between them.

Consider that sandstone, which began, some two billion years ago, as quartz crystals buried deep inside mountains towering over what is now the Upper Midwest and southern Canada. Time took apart the mountains, and rain dissolved most of the minerals in them, but the quartz remained. It was later washed into Precambrian rivers and eventually carried to a beach, where its grains were worn smooth and spherical by the waves. That beach was tropical, partly because the contemporaneous climate was extremely warm, but also because Wisconsin, at the time, was near the equator. As the sea retreated and other rocks and minerals were deposited on top of the former strand, the grains of quartz hardened into sandstone, which was gradually sculpted by wind, water, and glacier until, aboveground, it formed the topography of Wisconsin as we know it today. Belowground, it formed an excellent aquifer, thanks to those spherical grains, which—“like marbles in a jar,” as Bjornerud puts it—leave plenty of room for storing water in between them.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

My Papa’s Waltz

The whisky on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

by Theodore Roethke

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

What is Poetry?

Gozo Yoshimasu at Words Without Borders:

I only write in Japanese, a language that is plural by nature. It’s a language that has embraced several languages in its making, so you may hear the Chinese of the Tang, Song, Ming, or Qing periods, or the languages of Okinawa, Ainu, or Korea resonating within it. Asia is a region with an extensive history of a totally different sort from the West. Like in Africa, I guess, we inherit a thick layer of profound time in our basal memory that shapes our physical and mental subconscious gestures, and we always have to remember that.

I only write in Japanese, a language that is plural by nature. It’s a language that has embraced several languages in its making, so you may hear the Chinese of the Tang, Song, Ming, or Qing periods, or the languages of Okinawa, Ainu, or Korea resonating within it. Asia is a region with an extensive history of a totally different sort from the West. Like in Africa, I guess, we inherit a thick layer of profound time in our basal memory that shapes our physical and mental subconscious gestures, and we always have to remember that.

That being said, Japanese is too complicated to discuss, so let me return to the topic of poetry. I know from experience that my mind goes blank if I’m suddenly given a pen or pencil and asked to write poetry. And that’s what matters. While discussing translation, Walter Benjamin advocated a concept of “pure language” as an extreme goal of all languages. Supposing that every language aspires to this “pure language,” we must make efforts to set our sights on it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Plankton and the origins of life on Earth

Ferris Jabr in The Guardian:

Broadly speaking, plankton fall into two big categories – the plant-like phytoplankton and the animal-like zooplankton – though quite a few species have characteristics of both. Cyanobacteria and other microbial, ocean-dwelling phytoplankton are Earth’s original photosynthesizers. About half of all photosynthesis on the planet today occurs within their cells.

Broadly speaking, plankton fall into two big categories – the plant-like phytoplankton and the animal-like zooplankton – though quite a few species have characteristics of both. Cyanobacteria and other microbial, ocean-dwelling phytoplankton are Earth’s original photosynthesizers. About half of all photosynthesis on the planet today occurs within their cells.

Single-celled algae known as diatoms comprise another widespread group of phytoplankton. Diatoms have glass exoskeletons: they encase themselves in rigid, perforated and often iridescent capsules of silica, the main component of glass, which fit together as neatly as the two halves of a cookie tin. A different group of microalgae, the coccolithophores, also sheathe themselves in armour – made not of glass but of chalk. They construct shells out of overlapping scales of calcium carbonate, the mineral from which limestone and marble are composed, and which was once commonly used to write on blackboards.

Just as plants form the base of the food chain on land, phytoplankton nourish the seas. Zooplankton eat their green cousins as well as each other. Radiolarians are single-celled zooplankton that, like diatoms, produce glass skeletons from silica.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

While a sci-fi-style AI apocalypse is not impossible, more immediate risks to both security and democracy must be addressed

From Project Syndicate:

We all know the trope: a machine grows so intelligent that its apparent consciousness becomes indistinguishable from our own, and then it surpasses us – and possibly even turns against us. As investment pours into efforts to make such technology – so-called artificial general intelligence (AGI) – a reality, how scared of such scenarios should we be?

We all know the trope: a machine grows so intelligent that its apparent consciousness becomes indistinguishable from our own, and then it surpasses us – and possibly even turns against us. As investment pours into efforts to make such technology – so-called artificial general intelligence (AGI) – a reality, how scared of such scenarios should we be?

According to MIT’s Daron Acemoglu, the focus on “catastrophic risks due to AGI” is excessive and misguided, because it “(unhelpfully) anthropomorphizes AI” and “leads us to focus on the wrong targets.” A more productive discussion would focus on the factors that will determine whether AI is used for good or bad: “who controls [the technology], what their objectives are, and what kind of regulations they are subjected to.”

Joseph S. Nye, Jr., agrees that, whatever might happen with AGI in the future, the “growing risks from today’s narrow AI,” such as autonomous weapons and new forms of biological warfare, “already demand greater attention.” China, he points out, is already betting big on an “AI arms race,” seeking to benefit from “structural advantages” such as the relative lack of “legal or privacy limits on access to data” for training models.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Steven Plotkin: The evolution of multicellularity

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Analytical Philosophy – Arthur Danto (1967)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Michel Leiris’s Songs Of Himself

Sasha Frere-Jones at Bookforum:

MICHEL LEIRIS WAS A SMALL, polite French man who stayed alive for most of the twentieth century and wrote a deliciously dense memoir in four bricks called The Rules of the Game. The final chunk—Frêle Bruit, whose title has been translated by Richard Sieburth as Frail Riffs,rather than the more straightforward “faint noise”—is now finally available in English. This memoir project spans the years 1948 to 1976, which is roughly the middle of Leiris’s writing career. There were, in fact, memoirs published before and after this project, and a massive set of journals (only available in French as of now) that stretch across his life from young adulthood right up to death. Taken in sum, almost all of Leiris’s writings qualify as what he called “essais autobiographiques.”

MICHEL LEIRIS WAS A SMALL, polite French man who stayed alive for most of the twentieth century and wrote a deliciously dense memoir in four bricks called The Rules of the Game. The final chunk—Frêle Bruit, whose title has been translated by Richard Sieburth as Frail Riffs,rather than the more straightforward “faint noise”—is now finally available in English. This memoir project spans the years 1948 to 1976, which is roughly the middle of Leiris’s writing career. There were, in fact, memoirs published before and after this project, and a massive set of journals (only available in French as of now) that stretch across his life from young adulthood right up to death. Taken in sum, almost all of Leiris’s writings qualify as what he called “essais autobiographiques.”

Leiris often reminds me of artists like Chris Marker who work across disciplines and scatter their thoughts hither and yon, poets who put their work into different containers precisely to fight against a quick summary of their intentions. Leiris gestures at least once to the fact that this memoir—“too waxed, too polished”—is as much an act of poetry as it is a form of reporting.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

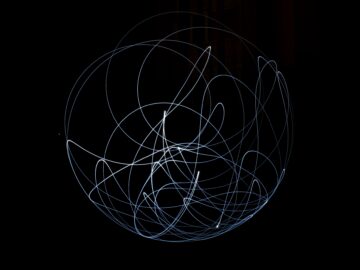

Can A Butterfly’s Wings Trigger A Distant Hurricane?

Erik Van Aken at Aeon Magazine:

A slight shift in Cleopatra’s beauty, and the Roman Empire unravels. You miss your train, and an unexpected encounter changes the course of your life. A butterfly alights from a tree in Michoacán, triggering a hurricane halfway across the globe. These scenarios exemplify the essence of ‘chaos’, a term scientists coined during the middle of the 20th century, to describe how small events in complex systems can have vast, unpredictable consequences.

A slight shift in Cleopatra’s beauty, and the Roman Empire unravels. You miss your train, and an unexpected encounter changes the course of your life. A butterfly alights from a tree in Michoacán, triggering a hurricane halfway across the globe. These scenarios exemplify the essence of ‘chaos’, a term scientists coined during the middle of the 20th century, to describe how small events in complex systems can have vast, unpredictable consequences.

Beyond these anecdotes, I want to tell you the story of chaos and answer the question: ‘Can the simple flutter of a butterfly’s wings truly trigger a distant hurricane?’ To uncover the layers of this question, we must first journey into the classical world of Newtonian physics. What we uncover is fascinating – the Universe, from the grand scale of empires to the intimate moments of daily life, operates within a framework where chaos and order are not opposites but intricately connected forces.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

The Way of Art

It seems to me that,

paralleling the paths of action, devotion, etc.,

there is a path called art

and that the sages of the East would recognize

Faulkner, Edward Hopper, Beethoven, William Carlos Williams

and address them as equals.

It’s a matter of intention and discipline, isn’t it? —

combined with a certain amount of God-given ability.

It’s what you’re willing to go through, willing to give, isn’t it?

It’s the willingness to be a window

through which others can see

all the way out to infinity

and all the way back to themselves.

by Albert Huffstickler

from Why I Write in Coffee Houses and Diners.

The Deeper Issue With Expanding Assisted Dying to Mental Illness

Elyse Weingarten in Undark:

In 2016, Canada enacted the Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAID, law, allowing individuals with a terminal illness to receive help from a medical professional to end their life. Following a superior court ruling, the legislation was expanded in 2021 to include nearly anyone with a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” causing “enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them.”

In 2016, Canada enacted the Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAID, law, allowing individuals with a terminal illness to receive help from a medical professional to end their life. Following a superior court ruling, the legislation was expanded in 2021 to include nearly anyone with a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” causing “enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them.”

Whether mental illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia, and addiction should be considered “grievous and irremediable” quickly emerged as the subject of intense debate. Initially slated to go into effect in March 2023, a new mental health provision of the law was postponed a year due to public outcry both in Canada and abroad. Then, in February, Health Minister Mark Holland announced it had been delayed again — this time until 2027 — to allow more time for the country’s health care system to prepare.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.