J. W. McCormack in the NY Review of Books:

Television’s best jokes turn hierarchies upside-down. In some cases ghoulish beauty standards are treated as ordinary, like when Morticia Addams clips the heads off roses to display the thorny stems, or when comely Marilyn Munster feels like the outcast in a family of vampires and Frankensteins. In others an authority figure gets taken for a perp or lowlife. Consider Peter Falk’s Lieutenant Columbo, the disheveled detective who spent much of the 1970s as the tentpole of NBC’s prime-time mystery programming block. Throughout the series he finds himself mistaken for various riffraff. At a soup kitchen where he’s collecting testimony, an overzealous nun assumes he’s without a home and needs a meal; at a porno shop where he’s following up on a clue, a customer takes him for a fellow pervert; at a crime scene, a policeman dismisses him as a rubberneck until he bashfully admits to being the investigating officer.

It’s an easy mistake to make. Columbo expects to be underestimated. In fact he’s counting on it. He always wears an earth-tone, threadbare raincoat, unless it’s raining. (Falk requested that the detective’s costume be made to look more Italian: “Everything is brown there, including the buildings. The Italians really understand that color best.”) He treats murder scenes in a decidedly unhygienic way, dropping cigar ashes all over the premises and indelicately touching the corpse. He veils his intelligence in a fog of stagy absentmindedness: his famous catchphrase, before clinching the case, is “Just one more thing.” Columbo is, in the words of one criminal, “a sly little elf [who] should be sitting under your own private little toadstool.” Elaine May reportedly called him “an ass-backward Sherlock Holmes.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The central gag of Slough House, the organization, is that the worst spies in London have been thrown together in one building and punished with terrible, useless jobs. When MI5 rookie River Cartwright is sent to Slough House, for example, he’s put to work sorting through garbage he steals from bins. When he asks Jackson Lamb, his boss, what he’s meant to be looking for, Lamb cracks, “The remnants of a once promising career.”

The central gag of Slough House, the organization, is that the worst spies in London have been thrown together in one building and punished with terrible, useless jobs. When MI5 rookie River Cartwright is sent to Slough House, for example, he’s put to work sorting through garbage he steals from bins. When he asks Jackson Lamb, his boss, what he’s meant to be looking for, Lamb cracks, “The remnants of a once promising career.” I

I S

S What is a novel, or any work of art, but the product of its time, of commerce? What is it but another colorful consumer unit, to be slid dutifully on a shelf or hawked through the internet? I’ve been mulling, of late, actions and reactions, the trope of the lone genius and the trope of systems. One held very long in the culture before being defenestrated, in academia at least, over the last several decades. The other is now dominant—at least, among those in the know, those who still analyze literature. In a systems conception, the genius of creation is disregarded and dismissed; no lone spark could truly emerge, no individual could labor, by herself, to write the novels, poems, or plays that endure across the ages, or even get remembered a decade after publication. Christian Lorentzen’s

What is a novel, or any work of art, but the product of its time, of commerce? What is it but another colorful consumer unit, to be slid dutifully on a shelf or hawked through the internet? I’ve been mulling, of late, actions and reactions, the trope of the lone genius and the trope of systems. One held very long in the culture before being defenestrated, in academia at least, over the last several decades. The other is now dominant—at least, among those in the know, those who still analyze literature. In a systems conception, the genius of creation is disregarded and dismissed; no lone spark could truly emerge, no individual could labor, by herself, to write the novels, poems, or plays that endure across the ages, or even get remembered a decade after publication. Christian Lorentzen’s  But I’d like to turn, at least at the outset, to a consideration of the sheer artistry of Morrison’s film, how even though its pacing is entirely dictated by the inevitable facticity and specificity of the tick-tock of the film’s method (all Morrison has done is to expertly align the time-signatures of a wide array of simultaneously running cameras and then cut in and out amongst them, guiding the viewer’s attention across a shifting grid of all that simultaneity), it is still remarkable how many editorially flecked or at any rate consciously discerned and foregrounded themes nevertheless emerge.

But I’d like to turn, at least at the outset, to a consideration of the sheer artistry of Morrison’s film, how even though its pacing is entirely dictated by the inevitable facticity and specificity of the tick-tock of the film’s method (all Morrison has done is to expertly align the time-signatures of a wide array of simultaneously running cameras and then cut in and out amongst them, guiding the viewer’s attention across a shifting grid of all that simultaneity), it is still remarkable how many editorially flecked or at any rate consciously discerned and foregrounded themes nevertheless emerge.  On its surface, the book is deceptively simple. At first hating Svalbard and seeing only bleak desolation, she undergoes a change, learning a great deal about herself, humanity, and the wild in the process. This is a cliched appraisal of the book, but part of its charm is how clearly these beats are telegraphed, and how skillfully she delivers on what you already suspect is coming.

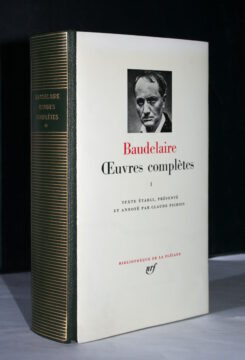

On its surface, the book is deceptively simple. At first hating Svalbard and seeing only bleak desolation, she undergoes a change, learning a great deal about herself, humanity, and the wild in the process. This is a cliched appraisal of the book, but part of its charm is how clearly these beats are telegraphed, and how skillfully she delivers on what you already suspect is coming. The same week this new two-volume edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Œuvres complètes arrived in bookshops, Spotify unveiled a new advert in the Paris Métro. It read: “You knew Le Spleen de Paris, here’s the Spleen of La Courneuve”. In the heart of the Seine-Saint-Denis banlieue, La Courneuve is a few miles north of the centre of Paris, where Baudelaire was born and mostly raised. On the other side of the périphérique ring road, it is where Jules Jomby’s family moved from Cameroon when he was six. Jules grew up in the blocks of council flats called the Cité des 4000, famously profiled in Jean-Luc Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967). Later, Jules was to adopt the stage name Dinos as he launched a successful rap career; later still, he was to draw inspiration from Baudelaire on his track “Spleen”, from his first studio album, Imany (2018).

The same week this new two-volume edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Œuvres complètes arrived in bookshops, Spotify unveiled a new advert in the Paris Métro. It read: “You knew Le Spleen de Paris, here’s the Spleen of La Courneuve”. In the heart of the Seine-Saint-Denis banlieue, La Courneuve is a few miles north of the centre of Paris, where Baudelaire was born and mostly raised. On the other side of the périphérique ring road, it is where Jules Jomby’s family moved from Cameroon when he was six. Jules grew up in the blocks of council flats called the Cité des 4000, famously profiled in Jean-Luc Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967). Later, Jules was to adopt the stage name Dinos as he launched a successful rap career; later still, he was to draw inspiration from Baudelaire on his track “Spleen”, from his first studio album, Imany (2018). From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs.

From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs. We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power?

We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power? I

I The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing

The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing  A

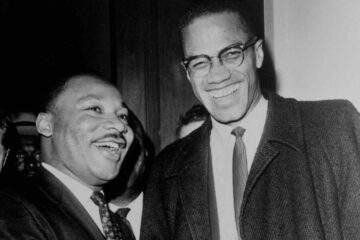

A  The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.