Danny Kelly at Literary Review:

From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs.

From its inception, pop (and rock) music was about youth. It offered a sound and a culture that stood in direct contrast, if not opposition, to the smugness of America’s Greatest Generation and to the choking conformity of postwar austerity Britain. It was made by the young, for the young. It was supposed to be ephemeral, disposable, temporary. The consumers would grow tired of the dance and move on to more adult, societally useful pursuits; the performers would have their moment in the spotlight, then develop jowls and get proper jobs.

For three decades (from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s) this pattern was largely followed. Pop stars came and went. Many of the greats – Buddy Holly, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Bob Marley, John Lennon, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones, Marc Bolan, Otis Redding (the sad pantheon is familiar) – died young, thus avoiding questions of post-fame irrelevance or how to navigate middle, never mind old, age. The rest were expected to retreat (depending on the deals they’d signed as starry-eyed hopefuls) to their stockbroker mansions or bedsit obscurity.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power?

We’re talking the day after the general election. How do you feel about Labour winning power? I

I The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing

The rape and killing of a 31-year-old woman medical resident has touched off protests across India as the country grapples with inadequate protections for women and increasing  A

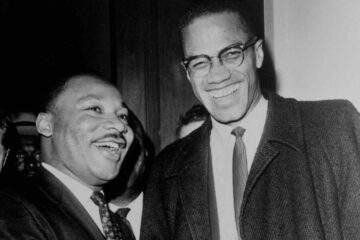

A  The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

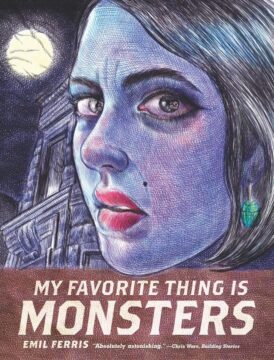

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 turns 60 on Tuesday. Its birthday is important because it is a living piece of legislation and a predecessor for laws impacting women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. I can’t help but think about this momentous act and its unifying power and be reminded of the time it brought together two of the greatest men of their generation – Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. THIS IS A GOTHIC TALE. In the summer of 2002, a professional illustrator and single mom in Chicago went to her fortieth-birthday bash, a gypsy-themed affair that her young daughter told her not to attend. A premonition? At the party, a mosquito bit her. Perhaps she slapped it dead; maybe it stayed attached, vampirically feasting. The result was no mere itch, but a health spiral. She had contracted West Nile disease, in a city very far from either side of that river, plus meningitis and encephalitis, paralyzing her lower body. Her drawing hand no longer worked: her livelihood was at stake. She moved in with her mother, whose dining room could accommodate her hospital bed and wheelchair, and enrolled in the fiction writing program at the Art Institute of Chicago. There were stories she wanted to tell. Maybe she’d revisit an abandoned screenplay from the ’90s, about “a werewolf lesbian girl being enfolded in the protective arms of a Frankenstein trans kid.”

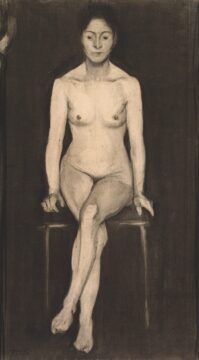

THIS IS A GOTHIC TALE. In the summer of 2002, a professional illustrator and single mom in Chicago went to her fortieth-birthday bash, a gypsy-themed affair that her young daughter told her not to attend. A premonition? At the party, a mosquito bit her. Perhaps she slapped it dead; maybe it stayed attached, vampirically feasting. The result was no mere itch, but a health spiral. She had contracted West Nile disease, in a city very far from either side of that river, plus meningitis and encephalitis, paralyzing her lower body. Her drawing hand no longer worked: her livelihood was at stake. She moved in with her mother, whose dining room could accommodate her hospital bed and wheelchair, and enrolled in the fiction writing program at the Art Institute of Chicago. There were stories she wanted to tell. Maybe she’d revisit an abandoned screenplay from the ’90s, about “a werewolf lesbian girl being enfolded in the protective arms of a Frankenstein trans kid.” MARRIAGE IS A GRIM BUSINESS—worse still if you’re a woman in a Rachel Cusk book. The blame lies with Christian iconography, she writes in her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, and pictures of the “holy family, that pious unit that sucked the world’s attention dry.” There, we found Mary and the manger, the Christ child, cuckolded Joseph: images gathered in a “cult of sentimentality and surfaces” to obscure the innate beastliness of human existence and so tidy death. They were fraudulent images, coercively “bent on veiling reality.” And who within the family is conscripted to perpetuate, if not precisely to manufacture, such images? Women. In becoming wives, we’re made stewards of our husbands, sainted sucklers of children, menders of life’s ripped seams. After the dissolution of a decade-long marriage, Cusk turned from Christianity to the myths of antiquity and the unconscious, that “tempestuous Greek world of feeling.” We are beings born of chaos, after all, disciplined by institutions but governed by affects and actions that stretch past the limits of our knowing and detonate the illusion of social order.

MARRIAGE IS A GRIM BUSINESS—worse still if you’re a woman in a Rachel Cusk book. The blame lies with Christian iconography, she writes in her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, and pictures of the “holy family, that pious unit that sucked the world’s attention dry.” There, we found Mary and the manger, the Christ child, cuckolded Joseph: images gathered in a “cult of sentimentality and surfaces” to obscure the innate beastliness of human existence and so tidy death. They were fraudulent images, coercively “bent on veiling reality.” And who within the family is conscripted to perpetuate, if not precisely to manufacture, such images? Women. In becoming wives, we’re made stewards of our husbands, sainted sucklers of children, menders of life’s ripped seams. After the dissolution of a decade-long marriage, Cusk turned from Christianity to the myths of antiquity and the unconscious, that “tempestuous Greek world of feeling.” We are beings born of chaos, after all, disciplined by institutions but governed by affects and actions that stretch past the limits of our knowing and detonate the illusion of social order. The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.”

The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.” After a lull of nearly 2 decades, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some novel drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease since 2021. Most of these drugs are antibody therapies targeting toxic protein aggregates in the brain. Their approval has sparked enthusiasm and controversy in equal measure. The core question remains: Are these drugs making a real difference? In this Special Feature, we investigate. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that involves a gradual and irreversible decline in memory, thinking, and, eventually, the ability to perform daily activities. Aging is the leading risk factor for

After a lull of nearly 2 decades, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some novel drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease since 2021. Most of these drugs are antibody therapies targeting toxic protein aggregates in the brain. Their approval has sparked enthusiasm and controversy in equal measure. The core question remains: Are these drugs making a real difference? In this Special Feature, we investigate. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that involves a gradual and irreversible decline in memory, thinking, and, eventually, the ability to perform daily activities. Aging is the leading risk factor for  At some point in the early morning, having forfeited my grip on the laminate, I was squeezed onto a balcony between Klaus and a very tall Polish American man, who was telling us about an upcoming trip to Kerala, where he would seek ayurvedic realignment after a season of encounters with unmitigated evil in Berlin. A third figure in a stiff leather jacket produced a red packet of cigarettes and distributed them with gravity, as if they were full-bodied charms. Klaus asked a question. Did you know that American Spirit was founded by one of Kojève’s graduate students, who named the tobacco company after Hegelian Spirit or Geist? I did not. This is the same Alexandre Kojève who had been born into Russian aristocracy, fled to Berlin after the October Revolution (and after an arrest for black-marketing soap), financed his early life by selling off the family jewels, enshrined himself as a chief architect of the European Economic Community, spied for the Kremlin for decades (or so it has been posthumously conjectured, without thorough proof), and did more than any other philosopher to shape the reception of Hegel’s thought in twentieth-century Europe. He was also, it seems, fond of anecdote, and liked to recycle one in particular. It went something like… when Hegel was asked, during a lecture on the philosophy of history, about the spirit of America, he thought for a moment and then replied: tobacco!

At some point in the early morning, having forfeited my grip on the laminate, I was squeezed onto a balcony between Klaus and a very tall Polish American man, who was telling us about an upcoming trip to Kerala, where he would seek ayurvedic realignment after a season of encounters with unmitigated evil in Berlin. A third figure in a stiff leather jacket produced a red packet of cigarettes and distributed them with gravity, as if they were full-bodied charms. Klaus asked a question. Did you know that American Spirit was founded by one of Kojève’s graduate students, who named the tobacco company after Hegelian Spirit or Geist? I did not. This is the same Alexandre Kojève who had been born into Russian aristocracy, fled to Berlin after the October Revolution (and after an arrest for black-marketing soap), financed his early life by selling off the family jewels, enshrined himself as a chief architect of the European Economic Community, spied for the Kremlin for decades (or so it has been posthumously conjectured, without thorough proof), and did more than any other philosopher to shape the reception of Hegel’s thought in twentieth-century Europe. He was also, it seems, fond of anecdote, and liked to recycle one in particular. It went something like… when Hegel was asked, during a lecture on the philosophy of history, about the spirit of America, he thought for a moment and then replied: tobacco! This disinclination to reread the books I treasure alienates me not just from Nabokov, but from a vast pro-rereading discourse espoused by geniuses who regard rereading as the literary activity par excellence. Roland Barthes, for instance, proposed that rereading is necessary if we are to realize the true goal of literature, which, in his view, is to make the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.” When we reread, we discover how a text can multiply in its variety and its plurality. Rereading offers something beyond a more detailed comprehension of the text: it is, Barthes claims, “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’).” I’m not so sure.

This disinclination to reread the books I treasure alienates me not just from Nabokov, but from a vast pro-rereading discourse espoused by geniuses who regard rereading as the literary activity par excellence. Roland Barthes, for instance, proposed that rereading is necessary if we are to realize the true goal of literature, which, in his view, is to make the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.” When we reread, we discover how a text can multiply in its variety and its plurality. Rereading offers something beyond a more detailed comprehension of the text: it is, Barthes claims, “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’).” I’m not so sure. Opening her late-summer set in Gunnersbury Park, west London, PJ Harvey sang: “Wyman, am I worthy?/Speak your wordle to me.” A pink haze had settled across the sky just before she appeared onstage to the sound of birdsong, church bells, and electronic fuzz. In the lyric – which comes from “Prayer at the Gate”, the opening track of her most recent record I Inside the Old Year Dying – Harvey sings in the dialect of her native Dorset. Wyman-Elvis is a Christ-like figure, literally an all-wise warrior, who appears throughout the album, and “wordle” is the world. For the next hour and a half, as the sky darkens and Harvey and her four-piece band perform underneath a low, red-tinged moon, they conjure their own wordle, one of riddles and disquieting enchantment.

Opening her late-summer set in Gunnersbury Park, west London, PJ Harvey sang: “Wyman, am I worthy?/Speak your wordle to me.” A pink haze had settled across the sky just before she appeared onstage to the sound of birdsong, church bells, and electronic fuzz. In the lyric – which comes from “Prayer at the Gate”, the opening track of her most recent record I Inside the Old Year Dying – Harvey sings in the dialect of her native Dorset. Wyman-Elvis is a Christ-like figure, literally an all-wise warrior, who appears throughout the album, and “wordle” is the world. For the next hour and a half, as the sky darkens and Harvey and her four-piece band perform underneath a low, red-tinged moon, they conjure their own wordle, one of riddles and disquieting enchantment. The impact of this work probably has nothing to do with whether it is high art masquerading as low art or low art masquerading as high art. Haring himself never seemed particularly interested in those divisions anyway. He liked Dubuffet and Alechinsky in exactly the same way that he liked cartoons and street graffiti. Pace Kuspit, I don’t think you can say that Haring’s art was fundamentally populist with a dash of high art influence to keep it from getting stale.

The impact of this work probably has nothing to do with whether it is high art masquerading as low art or low art masquerading as high art. Haring himself never seemed particularly interested in those divisions anyway. He liked Dubuffet and Alechinsky in exactly the same way that he liked cartoons and street graffiti. Pace Kuspit, I don’t think you can say that Haring’s art was fundamentally populist with a dash of high art influence to keep it from getting stale.