From BlackPast:

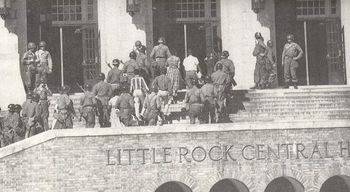

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court declared public school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. The Board of Education. One year later the Court reiterated its ruling calling on school districts throughout the United States to desegregate their public schools “with all deliberate speed.” While some school districts began developing strategies to resist public school desegregation, school officials at Little Rock, Arkansas stated that they would comply with the Supreme Court's ruling. School district officials created a system in which black students interested in attending white only schools were put through a series of rigorous interviews to determine whether they were suited for admission. School officials interviewed approximately eighty black students for Central High School, the largest school in the city. Only nine were chosen, Melba Patillo Beals, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Carlotta Walls Lanier, Terrance Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, Minnijean Brown Trickey, and Thelma Mothershed Wair. They would later become known around the world as the “Little Rock Nine.” Although skeptical about integrating a former white-only institution, the nine students arrived at Central High School on September 3, 1957 looking forward to a successful academic year. Instead they were greeted by an angry mob of white students, parents, and citizens determined to stop integration. In addition to facing physical threats, screams, and racial slurs from the crowd, Arkansas Governor Orval M. Faubus intervened, ordering the Arkansas National Guard to keep the nine African American students from entering the school. Faced with no other choice, the “Little Rock Nine” gave up their attempt to attend Central High School which soon became the center of a national debate about civil rights, racial discrimination and States’s rights.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court declared public school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. The Board of Education. One year later the Court reiterated its ruling calling on school districts throughout the United States to desegregate their public schools “with all deliberate speed.” While some school districts began developing strategies to resist public school desegregation, school officials at Little Rock, Arkansas stated that they would comply with the Supreme Court's ruling. School district officials created a system in which black students interested in attending white only schools were put through a series of rigorous interviews to determine whether they were suited for admission. School officials interviewed approximately eighty black students for Central High School, the largest school in the city. Only nine were chosen, Melba Patillo Beals, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Carlotta Walls Lanier, Terrance Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, Minnijean Brown Trickey, and Thelma Mothershed Wair. They would later become known around the world as the “Little Rock Nine.” Although skeptical about integrating a former white-only institution, the nine students arrived at Central High School on September 3, 1957 looking forward to a successful academic year. Instead they were greeted by an angry mob of white students, parents, and citizens determined to stop integration. In addition to facing physical threats, screams, and racial slurs from the crowd, Arkansas Governor Orval M. Faubus intervened, ordering the Arkansas National Guard to keep the nine African American students from entering the school. Faced with no other choice, the “Little Rock Nine” gave up their attempt to attend Central High School which soon became the center of a national debate about civil rights, racial discrimination and States’s rights.

On September 20, 1957, Federal Judge Ronald Davies ordered Governor Faubus to remove the National Guard from the Central High School’s entrance and to allow integration to take its course in Little Rock. When Faubus defied the court order, President Dwight Eisenhower dispatched nearly 1,000 paratroopers and federalized the 10,000 Arkansas National Guard troops who were to insure that the school would be open to the nine students. On September 23, 1957, the “Little Rock Nine” returned to Central High School where they were enrolled. Units of the United States Army remained at the school for the rest of the academic year to guarantee their safety.

More here. (Note: At leas t one daily post throughout February will be devoted to African American History Month)