From The Guardian:

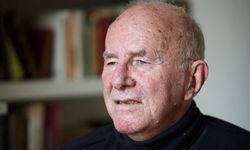

“I'm told that I'm looking quite shiny,” says Clive James, putting his best face on things with a vintage display of Anglo-Australian stoicism. It's an instinctive optimism that is what you'd expect, but still it is moving. Almost everything in the life of this great literary polymath is edged with darkness. James now dwells in a kind of internal exile: from family, from good health and from convivial literary association, even from his own native land. His circumstances in old age – James is 73 – evoke a fate that Dante might plausibly have inflicted on a junior member of the damned in one of the less exacting circles of hell. James's health has lately been so bad that, last year, he was obliged publicly to deny a viral rumour of his imminent demise. Two or three times, indeed, since falling ill on New Year's day in 2010, he has nearly died, but has somehow contrived (so far) to play the Comeback Kid. Perhaps he has found rejuvenation in the macabre satisfaction of reading premature rave obituaries from fans around the English-speaking world. If word of his death has been exaggerated, there's no question, on meeting him, that he's into injury time, with a nagging cough that punctuates our conversation. “Essentially,” he says, as we settle into the rather spartan living room of his two-up, two-down terraced house in Cambridge, “I've got the lot. Leukaemia is lurking, but it's in remission. The thing that rips up my chest is the emphysema. Plus I've got all kinds of little carcinomas.” He points to the place on his right ear where a predatory oncologist has recently removed a threatening growth. “I'd love to see Australia again,” he reflects. “But I can't go further than three weeks away from Addenbrooke's hospital, so that means I'm here in Cambridge.”

“I'm told that I'm looking quite shiny,” says Clive James, putting his best face on things with a vintage display of Anglo-Australian stoicism. It's an instinctive optimism that is what you'd expect, but still it is moving. Almost everything in the life of this great literary polymath is edged with darkness. James now dwells in a kind of internal exile: from family, from good health and from convivial literary association, even from his own native land. His circumstances in old age – James is 73 – evoke a fate that Dante might plausibly have inflicted on a junior member of the damned in one of the less exacting circles of hell. James's health has lately been so bad that, last year, he was obliged publicly to deny a viral rumour of his imminent demise. Two or three times, indeed, since falling ill on New Year's day in 2010, he has nearly died, but has somehow contrived (so far) to play the Comeback Kid. Perhaps he has found rejuvenation in the macabre satisfaction of reading premature rave obituaries from fans around the English-speaking world. If word of his death has been exaggerated, there's no question, on meeting him, that he's into injury time, with a nagging cough that punctuates our conversation. “Essentially,” he says, as we settle into the rather spartan living room of his two-up, two-down terraced house in Cambridge, “I've got the lot. Leukaemia is lurking, but it's in remission. The thing that rips up my chest is the emphysema. Plus I've got all kinds of little carcinomas.” He points to the place on his right ear where a predatory oncologist has recently removed a threatening growth. “I'd love to see Australia again,” he reflects. “But I can't go further than three weeks away from Addenbrooke's hospital, so that means I'm here in Cambridge.”

In a recent, valedictory poem, “Holding Court”, which describes his involuntary sequestration, he writes: “My wristband feels too loose around my wrist.” In all other respects, he is tightly shackled to his fate. Exiled from his homeland, where he has now become a much-loved grand old man of Australian letters, James is also exiled in Cambridge. His wife of 45 years, the Dante scholar Prue Shaw, kicked him out of the marital home last year on the disclosure of his long affair with a former model, Leanne Edelsten. This betrayal also devastated his two daughters, though it has ultimately brought them closer to their father. In “Holding Court”, James writes ruefully that “retreating from the world, all I can do, is build a new world”.

More here.