Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Imagine I went to a Hollywood studio with the following plot: It’s the year 2024. War is breaking out all over the world. Asia is threatened by communists; Europe, by fascists. Only America stands against these totalitarian empires, but its society is divided and its industry is outmatched. But there’s one man could save America — and, by extension, the world. A reclusive genius and peerless industrialist, he has built a fleet of gigantic rockets that can take off and land halfway across the world, blanketed the heavens with satellites, and created futuristic cars that singlehandedly revived America’s auto industry. He’s in the process of creating a colony on Mars. Oh, and he also owns the country’s most important social network, controlling the flow of information between journalists, politicians, and the public. But is this towering figure a superhero, or a supervillain? Between personal troubles (insert complex backstory here) and battles with smug government bureaucrats, he’s grown disillusioned. Agents of freedom’s enemies reach out to him, coveting his technological marvels for themselves. Will he save the day, or go over to the other side?

This proposal would probably get rejected. We already have one Iron Man,1 the studio exec would tell me. And for that matter we also have a Batman, a Dr. Doom, a Green Goblin, and an Adrian Veidt. We don’t need another of these guys. He’d hand me back my spec script and tell me to come back when I have something less derivative.

And yet somehow we find ourselves living in this comic-book reality. Even as American manufacturing (and German manufacturing, and Japanese manufacturing, etc.) has been hollowed out by Chinese competition and our great old companies have stumbled and declined, one single entrepreneur has been able to build and scale gigantic new cutting-edge high-tech world-beating manufacturing companies in the United States of America. That one man is Elon Musk.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

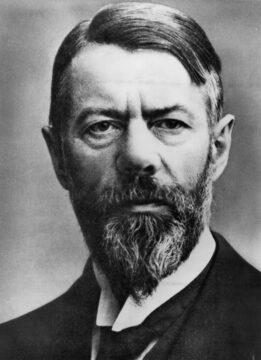

The professor and the politician are a dyad of perpetual myth. In one myth, they are locked in conflict, sparring over the claims of reason and the imperative of power. Think Socrates and Athens, or

The professor and the politician are a dyad of perpetual myth. In one myth, they are locked in conflict, sparring over the claims of reason and the imperative of power. Think Socrates and Athens, or  P

P

I think what confuses me so much about those who have prescriptions for how to write is that they assume all humans experience the world the same way. For instance, that we all think “conflict” is the most interesting and gripping part of life, and so we should all make conflict the heart of our fiction. Or that when we think of other people, we all think of what they look like. Or that we all believe things happen due to identifiable causes. Shouldn’t a writer be trained to pay attention to what they notice about life, what they think life is, and come up with ways of highlighting those things? The indifference to the unique relationship between the writer and their story (or between the writer and the reason they are writing), which is necessarily a by-product of any generalized writing advice, is part of what makes the comedy in this book so great. As a teacher, “Sam Shelstad” is so literal, and takes the conventions of how to write successful fiction on such faith, that when he tries to relay these tips to his reader, the advice ends up sounding as absurd as it actually is.

I think what confuses me so much about those who have prescriptions for how to write is that they assume all humans experience the world the same way. For instance, that we all think “conflict” is the most interesting and gripping part of life, and so we should all make conflict the heart of our fiction. Or that when we think of other people, we all think of what they look like. Or that we all believe things happen due to identifiable causes. Shouldn’t a writer be trained to pay attention to what they notice about life, what they think life is, and come up with ways of highlighting those things? The indifference to the unique relationship between the writer and their story (or between the writer and the reason they are writing), which is necessarily a by-product of any generalized writing advice, is part of what makes the comedy in this book so great. As a teacher, “Sam Shelstad” is so literal, and takes the conventions of how to write successful fiction on such faith, that when he tries to relay these tips to his reader, the advice ends up sounding as absurd as it actually is. At

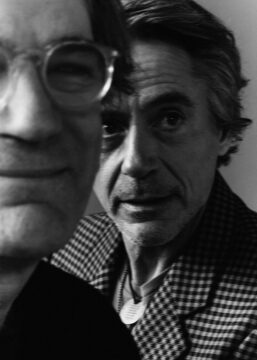

At  This summer, Ayad Akhtar was struggling with the final scene of “McNeal,” his knotty and disorienting play about a Nobel Prize-winning author who uses artificial intelligence to write a novel. He wanted the title character, played by Robert Downey Jr. in his Broadway debut, to deliver a monologue that sounded like a computer wrote it. So Akhtar uploaded what he had written into ChatGPT, gave the program a list of words, and told it to produce a speech in the style of Shakespeare. The results were so compelling that he read the speech to the cast at the next rehearsal.

This summer, Ayad Akhtar was struggling with the final scene of “McNeal,” his knotty and disorienting play about a Nobel Prize-winning author who uses artificial intelligence to write a novel. He wanted the title character, played by Robert Downey Jr. in his Broadway debut, to deliver a monologue that sounded like a computer wrote it. So Akhtar uploaded what he had written into ChatGPT, gave the program a list of words, and told it to produce a speech in the style of Shakespeare. The results were so compelling that he read the speech to the cast at the next rehearsal. The passage from Enlightenment to Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century was perhaps the most deeply felt crisis in European intellectual history. The Age of Reason had seen such extraordinary strides in scientific discovery and political liberty that the future progress of both mind and society seemed to many already marked out. Two groups of people were unhappy about this. Traditionalists, both religious and political, regarded the party of Reason as a nuisance, to be swatted away rather than argued with in earnest. The Enlightenment’s scientific materialism and anti-authoritarianism seemed to them sheer perversity, old heresies in a new garb. But by the time the party of Reason morphed into the party of Revolution, it was too late for swatting; and by the mid-nineteenth century the traditionalists had retreated into a long defensive crouch that lasted until quite recently.

The passage from Enlightenment to Romanticism at the end of the eighteenth century was perhaps the most deeply felt crisis in European intellectual history. The Age of Reason had seen such extraordinary strides in scientific discovery and political liberty that the future progress of both mind and society seemed to many already marked out. Two groups of people were unhappy about this. Traditionalists, both religious and political, regarded the party of Reason as a nuisance, to be swatted away rather than argued with in earnest. The Enlightenment’s scientific materialism and anti-authoritarianism seemed to them sheer perversity, old heresies in a new garb. But by the time the party of Reason morphed into the party of Revolution, it was too late for swatting; and by the mid-nineteenth century the traditionalists had retreated into a long defensive crouch that lasted until quite recently. Beginning in late September,

Beginning in late September,  In May 2018, Childish Gambino (Donald Glover’s musical alter-ego) dropped the single

In May 2018, Childish Gambino (Donald Glover’s musical alter-ego) dropped the single  I

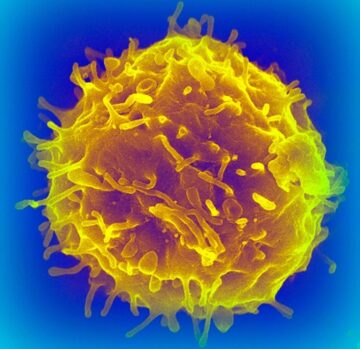

I Ever since the first blood-forming stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with blood cancers more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they developed

Ever since the first blood-forming stem cells were successfully transplanted into people with blood cancers more than 50 years ago, researchers have wondered whether they developed  THE YEAR IS 1906. Theodore Roosevelt is in the White House. In New York, the newspapers are reporting on the political aspirations of William Randolph Hearst, unrest in Russia, and the latest dividends from US Steel. Scientific American is running articles about exploring the Sargasso Sea. In Boston, The New England Journal of Medicine is discussing new treatments for typhus and tuberculosis. Upton Sinclair’s new novel The Jungle, recently out from Doubleday, portrays the oppressive working conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry—Jack London calls it “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery”—and it’s taking the country by storm. In October, the Chicago White Sox play the Cubs in the country’s first intracity World Series, which the Sox go on to win (in a massive upset) four games to two.

THE YEAR IS 1906. Theodore Roosevelt is in the White House. In New York, the newspapers are reporting on the political aspirations of William Randolph Hearst, unrest in Russia, and the latest dividends from US Steel. Scientific American is running articles about exploring the Sargasso Sea. In Boston, The New England Journal of Medicine is discussing new treatments for typhus and tuberculosis. Upton Sinclair’s new novel The Jungle, recently out from Doubleday, portrays the oppressive working conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry—Jack London calls it “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery”—and it’s taking the country by storm. In October, the Chicago White Sox play the Cubs in the country’s first intracity World Series, which the Sox go on to win (in a massive upset) four games to two.