Ezra Klein in the New York Times:

In his book “The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order,” the historian Gary Gerstle introduced me to this concept of political orders, these structures of political consensus that stretch over decades. There were two across the 20th century: the New Deal order, which ran from the 1930s to the 1970s, and the neoliberal order, which stretched from the ’70s to the financial crisis. And I wonder if part of what is unsettling politics right now is a random moment between orders, a moment when you can just begin to see the hazy outline of something new taking shape and both parties are in internal upheavals as they try to remake themselves, to grasp at it and respond to it.

In his book “The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order,” the historian Gary Gerstle introduced me to this concept of political orders, these structures of political consensus that stretch over decades. There were two across the 20th century: the New Deal order, which ran from the 1930s to the 1970s, and the neoliberal order, which stretched from the ’70s to the financial crisis. And I wonder if part of what is unsettling politics right now is a random moment between orders, a moment when you can just begin to see the hazy outline of something new taking shape and both parties are in internal upheavals as they try to remake themselves, to grasp at it and respond to it.

And I know where we are in the election cycle. I know where everybody’s minds are. I’ve got nothing to tell you about the polls. There’s nothing I can say that is going to allay your anxiety for a few days from now. And I know that within this feeling of the moment, it feels weird to talk at all about zones of possible agreement or compromise rather than disagreement and danger.

But I think it’s worth doing this episode in this conversation now because I think they’re important to understanding why this election has played out the way it has — and I think it’s important for thinking about where politics might be going next.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but sometimes you can judge a writer’s standing by it. My 1990s-era paperback edition of “The Portable Dorothy Parker” shows the poet, critic, playwright and resident wit of the Algonquin Round Table looking stricken. Her eyes are sunken and shadowy; her hair is barely tamed; her eyes are glazed. At the time, that’s how we liked her — American literature’s cautionary tale. A notice encourages the reader to go see “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle,” a bitter ensemble film from 1994 starring Jennifer Jason Leigh playing Parker as she begins to lose faith in writing, men and herself. Look at that book cover, and it’s clear the loss of faith is complete.

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but sometimes you can judge a writer’s standing by it. My 1990s-era paperback edition of “The Portable Dorothy Parker” shows the poet, critic, playwright and resident wit of the Algonquin Round Table looking stricken. Her eyes are sunken and shadowy; her hair is barely tamed; her eyes are glazed. At the time, that’s how we liked her — American literature’s cautionary tale. A notice encourages the reader to go see “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle,” a bitter ensemble film from 1994 starring Jennifer Jason Leigh playing Parker as she begins to lose faith in writing, men and herself. Look at that book cover, and it’s clear the loss of faith is complete. I see at least two reasons to doubt that we are ready to abandon past transcendent realities. First, our modern ideas about morality don’t make sense without them. When secular neo-Enlightenment humanists, neo-Kantians, and effective altruists champion equality and universal human rights, they are trying to pluck an ethic from its metaphysical roots. They are essentially preaching from the theistic pulpit after tearing down the crucifix. (And we saw how that worked out for effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried.) This hamstrung morality might limp along if the broader culture is still breathing the air of Christian values, even unconsciously, but the deeper we get inside the immanent frame, the more opportunity we give an anti-humanist Nietzsche to come along and say that our ethics are incompatible with our materialist anthropology. And what if this Nietzsche turns out to be an AI system that concludes that the best way to fix climate change is to wipe out humanity? Our moral demands may well be writing checks that our moral sources can’t cash.

I see at least two reasons to doubt that we are ready to abandon past transcendent realities. First, our modern ideas about morality don’t make sense without them. When secular neo-Enlightenment humanists, neo-Kantians, and effective altruists champion equality and universal human rights, they are trying to pluck an ethic from its metaphysical roots. They are essentially preaching from the theistic pulpit after tearing down the crucifix. (And we saw how that worked out for effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried.) This hamstrung morality might limp along if the broader culture is still breathing the air of Christian values, even unconsciously, but the deeper we get inside the immanent frame, the more opportunity we give an anti-humanist Nietzsche to come along and say that our ethics are incompatible with our materialist anthropology. And what if this Nietzsche turns out to be an AI system that concludes that the best way to fix climate change is to wipe out humanity? Our moral demands may well be writing checks that our moral sources can’t cash. The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath is an essential yet strangely discomforting volume. It includes writing so apparently far removed from the work for which Plath is remembered – her late poems and her autofictional novel The Bell Jar – that it almost seems to undermine her canonical status. In reality, of course, it does no such thing. Read alongside the works she’s famous for, it offers an insight into how young Sylvia became Sylvia Plath.

The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath is an essential yet strangely discomforting volume. It includes writing so apparently far removed from the work for which Plath is remembered – her late poems and her autofictional novel The Bell Jar – that it almost seems to undermine her canonical status. In reality, of course, it does no such thing. Read alongside the works she’s famous for, it offers an insight into how young Sylvia became Sylvia Plath. A

A “Mr. Handel’s head is more full of Maggots than ever. … I could tell you more … but it grows late & I must defer the rest until I write next; by which time, I doubt not, more new ones will breed in his Brain.”

“Mr. Handel’s head is more full of Maggots than ever. … I could tell you more … but it grows late & I must defer the rest until I write next; by which time, I doubt not, more new ones will breed in his Brain.” There were, of course, other ways to feel connected with humanity on a plane. You could notice a slight indentation left in the seat from the person before you, or the length to which they had extended (or shortened) their seatbelt, which would now become yours. You didn’t have to turn to the back of the in-flight magazine to see some stranger’s—or, more likely, strangers’—handiwork on the crossword, or wonder what flavor of sticky substance someone had spilled across its pages. Nor was it required to retrace the doodles drawn on the ads for UNTUCKit shirts, It’s Just Lunch, Hard Rock Café, Wellendorff jewelry, companies selling gold coins, and Big Green Eggs. But it’s clear that with the last print issue of Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine of United Airlines, and the last such magazine connected to a major US carrier (with the exception of Hana Hou!, for Hawaiian Airlines), it is the end of an era.

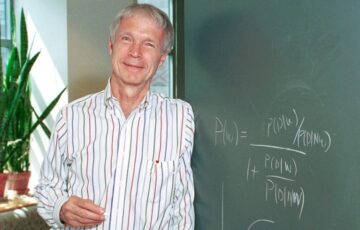

There were, of course, other ways to feel connected with humanity on a plane. You could notice a slight indentation left in the seat from the person before you, or the length to which they had extended (or shortened) their seatbelt, which would now become yours. You didn’t have to turn to the back of the in-flight magazine to see some stranger’s—or, more likely, strangers’—handiwork on the crossword, or wonder what flavor of sticky substance someone had spilled across its pages. Nor was it required to retrace the doodles drawn on the ads for UNTUCKit shirts, It’s Just Lunch, Hard Rock Café, Wellendorff jewelry, companies selling gold coins, and Big Green Eggs. But it’s clear that with the last print issue of Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine of United Airlines, and the last such magazine connected to a major US carrier (with the exception of Hana Hou!, for Hawaiian Airlines), it is the end of an era. John Hopfield, one of this year’s

John Hopfield, one of this year’s  The publication of new interviews with Donald Trump’s longstanding chief of staff John Kelly have been in the news since last week, and the Harris campaign has picked up on Kelly’s use of the word “fascist” to describe his former boss. This has reignited a longstanding debate over whether Trump and his MAGA movement represent the threat of genuine fascism in the United States were he to be re-elected.

The publication of new interviews with Donald Trump’s longstanding chief of staff John Kelly have been in the news since last week, and the Harris campaign has picked up on Kelly’s use of the word “fascist” to describe his former boss. This has reignited a longstanding debate over whether Trump and his MAGA movement represent the threat of genuine fascism in the United States were he to be re-elected. In the brief introduction to

In the brief introduction to