Leo Robson at The New Statesman:

In various ways, Pedro Almodóvar’s terrific new film represents a culmination or point of arrival. The Room Next Door, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, marks the director’s first time working in English and telling a story set entirely outside Spain. It is also a clear admission – from a film-maker strongly associated with costume, production design and bodies – of an essential bookishness: his belief, expressed in his recently published collection of stories The Last Dream, that his vocation is “literary”, and it’s merely a quirk of fate that the bulk of his written output has been 22 screenplays, which he also directed. The film concerns two writers, Ingrid, a war reporter suffering from cancer (Tilda Swinton), and Martha (Julianne Moore), a novelist with whom Ingrid spends her final weeks. Though Almodóvar does away with many of the reference points in the source material, Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through, he introduces plenty of his own. The Room Next Door opens at a Manhattan bookshop, where Martha is doing a signing, and ends with a quotation from “The Dead” – and it isn’t the only bookshop, or mention of James Joyce.

In various ways, Pedro Almodóvar’s terrific new film represents a culmination or point of arrival. The Room Next Door, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, marks the director’s first time working in English and telling a story set entirely outside Spain. It is also a clear admission – from a film-maker strongly associated with costume, production design and bodies – of an essential bookishness: his belief, expressed in his recently published collection of stories The Last Dream, that his vocation is “literary”, and it’s merely a quirk of fate that the bulk of his written output has been 22 screenplays, which he also directed. The film concerns two writers, Ingrid, a war reporter suffering from cancer (Tilda Swinton), and Martha (Julianne Moore), a novelist with whom Ingrid spends her final weeks. Though Almodóvar does away with many of the reference points in the source material, Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through, he introduces plenty of his own. The Room Next Door opens at a Manhattan bookshop, where Martha is doing a signing, and ends with a quotation from “The Dead” – and it isn’t the only bookshop, or mention of James Joyce.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tyler Cowen is an economics professor and blogger at

Tyler Cowen is an economics professor and blogger at

I

I It is incredibly difficult to say something new about social norms. The question “What is a social norm?” has been given many detailed answers by philosophers and social scientists. Social norms are often theorized as rules of some kind; most of the ensuing literature concerns the nature of such rules and how they are established or maintained. Despite the mountain of literature on social norms, Charlotte Witt’s Social Goodness not only makes an original contribution to the literature, but it also does so in a way that points toward important, underexplored regions of conceptual space.

It is incredibly difficult to say something new about social norms. The question “What is a social norm?” has been given many detailed answers by philosophers and social scientists. Social norms are often theorized as rules of some kind; most of the ensuing literature concerns the nature of such rules and how they are established or maintained. Despite the mountain of literature on social norms, Charlotte Witt’s Social Goodness not only makes an original contribution to the literature, but it also does so in a way that points toward important, underexplored regions of conceptual space. College towns are a little like Vegas. They’re fallen capitals, scourged by development and game-day apartments. The boomer professors got there and built the Museum of the American Rebel; soon after, they withered into Cadaver Bohemias. The Godfather, the department chair who hired me in 2016, was nonetheless confident that I’d assimilate to the sprawling “family” he had helped build there. “Faculty regard Oxford as a suburb of New Orleans,” he told me, referring to the city where I’d lived for more than a decade. “So it won’t be too much of a change.” It was an amiable conversation, in which he assured me he’d hired his first choices for the two posts they’d needed: me as an instructor, and the Superstar writer-in-residence, a bestselling novelist and infamous Twitter provocateur.

College towns are a little like Vegas. They’re fallen capitals, scourged by development and game-day apartments. The boomer professors got there and built the Museum of the American Rebel; soon after, they withered into Cadaver Bohemias. The Godfather, the department chair who hired me in 2016, was nonetheless confident that I’d assimilate to the sprawling “family” he had helped build there. “Faculty regard Oxford as a suburb of New Orleans,” he told me, referring to the city where I’d lived for more than a decade. “So it won’t be too much of a change.” It was an amiable conversation, in which he assured me he’d hired his first choices for the two posts they’d needed: me as an instructor, and the Superstar writer-in-residence, a bestselling novelist and infamous Twitter provocateur. You start your book by pointing out that all academic writers begin their careers writing for one person: their teacher. Why does that create problems?

You start your book by pointing out that all academic writers begin their careers writing for one person: their teacher. Why does that create problems? Went back to the gym after ten days out of town. On vacation in Oregon, with my family, I didn’t work out a single time. On the plane home, I watched an episode of Succession with Alexander Skarsgård in it and thought, I’d like to look like him. He probably works out even when he’s on vacation. But he’s rich, of course, and likely does other extreme things like steroids and blending chicken into smoothies. Still I would like to look more like Alexander Skarsgård than I currently do. I’m 6’3, almost his height, but far skinnier.

Went back to the gym after ten days out of town. On vacation in Oregon, with my family, I didn’t work out a single time. On the plane home, I watched an episode of Succession with Alexander Skarsgård in it and thought, I’d like to look like him. He probably works out even when he’s on vacation. But he’s rich, of course, and likely does other extreme things like steroids and blending chicken into smoothies. Still I would like to look more like Alexander Skarsgård than I currently do. I’m 6’3, almost his height, but far skinnier. A large economy is one of the best examples we have of complex dynamics. There are multiple components arranged in complicated overlapping hierarchies, out-of-equilibrium dynamics, nonlinear coupling and feedback between different levels, and ubiquitous unpredictable and chaotic behavior. Nevertheless, many economic models are based on relatively simple equilibrium principles. Doyne Farmer is among a group who think that economists need to start taking the tools of complexity theory seriously, as he argues in his recent book

A large economy is one of the best examples we have of complex dynamics. There are multiple components arranged in complicated overlapping hierarchies, out-of-equilibrium dynamics, nonlinear coupling and feedback between different levels, and ubiquitous unpredictable and chaotic behavior. Nevertheless, many economic models are based on relatively simple equilibrium principles. Doyne Farmer is among a group who think that economists need to start taking the tools of complexity theory seriously, as he argues in his recent book  For the next few weeks, Literary Hub will be going beyond the memes for an in-depth look at the everyday issues affecting Americans as they head to the polls on November 5th. Each week at Lit Hub we’ll be featuring reading lists, essays, and interviews on important topics like Income Inequality, Climate Justice, LGBTQ Rights, Reproductive Rights, and more. For a better handle on the issues affecting you and your loved ones—regardless of who ends up president on November 6th (or 7th, or 8th, or whenever)—stay tuned to LitHub.com in October. Read parts one and two,

For the next few weeks, Literary Hub will be going beyond the memes for an in-depth look at the everyday issues affecting Americans as they head to the polls on November 5th. Each week at Lit Hub we’ll be featuring reading lists, essays, and interviews on important topics like Income Inequality, Climate Justice, LGBTQ Rights, Reproductive Rights, and more. For a better handle on the issues affecting you and your loved ones—regardless of who ends up president on November 6th (or 7th, or 8th, or whenever)—stay tuned to LitHub.com in October. Read parts one and two,  D

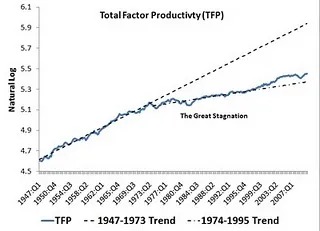

D Science in the United States has never been stronger by most measures.

Science in the United States has never been stronger by most measures.