Marek Kohn in More Intelligent Life:

Five times in the history of life on Earth, mass extinctions have eliminated at least three-quarters of the species that were present before each episode began. The likely exterminators were volcanoes, noxious gases, climatic upheavals and the asteroid that did for the dinosaurs. Now a single species threatens to wipe out most of the others that surround it. We are faced with the realisation, as the ecologist Robert May puts it, that we “can now do things which are on the scale of being hit by an asteroid”.

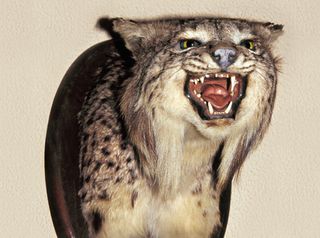

THE LYNX BECAME top predator in Doñana after the last wolf was shot in 1951. That is how it goes with predators and large animals. The bigger they are, the sooner they tend to vanish. Among mammals, the risk of extinction rises sharply for species that weigh more than three kilograms—about as much as a small pet cat. Big creatures need more food and more space to find it in than small ones; they are slower to reproduce, and are apt to get on the wrong side of humans. “The species that tend to go extinct first tend to be the big-bodied things, and the tasty things,” says Rob Ewers of Imperial College London. He is talking about the Amazon forests, but it’s a general truth.

Big animals, particularly those at the top of food chains, “are really fundamentally important to holding ecosystems together,” says Jim Estes, a biologist based at the University of California, Santa Cruz. When they go, ecosystems unravel and reorganise, removing more species in the process. “Apex consumers” can take whole habitats with them. Wolves may protect forests by preying on the deer that browse saplings. If the wolves are wiped out, the deer multiply at the expense of the trees, preventing the forest from renewing itself: the end-point, as on the once-forested Scottish island of Rùm, is a treeless landscape. Globally, the result is the “downgrading of Planet Earth”, as Estes put it in an article for the journal Science in 2011.

The exits began long before roads or rifles were devised. Nearly three-quarters of North American and a third of Eurasian megafauna disappeared between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago. Woolly mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, giant sloths and sabre-toothed cats were among the species that vanished from the face of the Earth. While climate change was one part of the story, human expansion was another. The selective disappearance of large animals marks this period out from other extinction episodes, and was the start of what Estes and his fellow authors suggested “is arguably humankind’s most pervasive influence on the natural world”. For Estes, it was the beginning of the sixth mass extinction.

More here.

Sylvia Plath said that writers are “the most narcissistic people”: whatever the truth of that statement, one can assume at least that her use of the term was correct. Freud bequeathed the modern era a tangled concept in narcissism, and literary culture has shown itself as apt as any other to misappropriate it. Yet it is the fashion to see people increasingly as one of two types – a narcissist, or the victim of one – so perhaps it is worth asking precisely what is meant by the word, which has come to encapsulate a cultural malaise.