Tony Ho Tran in Slate:

It’s a good way to spend a Saturday morning—if, admittedly, a strange one. I wake up and pack a tote bag with leather gardening gloves, a water bottle, a towel, and headphones. Then I drive to one of Chicago’s 272 cemeteries and spend hours taking pictures of the dead.

It’s a good way to spend a Saturday morning—if, admittedly, a strange one. I wake up and pack a tote bag with leather gardening gloves, a water bottle, a towel, and headphones. Then I drive to one of Chicago’s 272 cemeteries and spend hours taking pictures of the dead.

I do this once a month or so. Alongside shots of my dog and gym selfies, my phone’s camera roll is filled with photos of gravestones of all shapes, sizes, and materials: massive granite monuments fit for the Chicago industrialists buried underneath them, humble flat markers that I’m prone to tripping over, and sandstone slabs so worn down by centuries of sun, rain, and snow that there’s no telling who’s buried there.

I should say: It’s not just me. The photos I take end up on a website called FindaGrave.com, a repository of cemeteries around the world. Created in 1995 by a Salt Lake City resident named Jim Tipton, the website began as a place to catalog his hobby of visiting and documenting celebrity graves. In the late 1990s, Tipton began to allow other users to contribute their own photos and memorials for famous people as well. In 2010, Find a Grave finally allowed non-celebrities to be included. Since then, volunteers—also known as “gravers”—have stalwartly photographed and recorded tombstones, mausoleums, crosses, statues, and all other manner of graves for posterity.

I should say: It’s not just me. The photos I take end up on a website called FindaGrave.com, a repository of cemeteries around the world. Created in 1995 by a Salt Lake City resident named Jim Tipton, the website began as a place to catalog his hobby of visiting and documenting celebrity graves. In the late 1990s, Tipton began to allow other users to contribute their own photos and memorials for famous people as well. In 2010, Find a Grave finally allowed non-celebrities to be included. Since then, volunteers—also known as “gravers”—have stalwartly photographed and recorded tombstones, mausoleums, crosses, statues, and all other manner of graves for posterity.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Laskowski revealed that her ambition had drawn her into the web of prolific spider researcher Jonathan Pruitt, a behavioural ecologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Pruitt was a superstar in his field and, in 2018, was named a Canada 150 Research Chair, becoming one of the younger recipients of the prestigious federal one-time grant with funding of $350,000 per year for seven years. He amassed a huge number of publications, many with surprising and influential results. He turned out to be an equally prolific fraud.

Laskowski revealed that her ambition had drawn her into the web of prolific spider researcher Jonathan Pruitt, a behavioural ecologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Pruitt was a superstar in his field and, in 2018, was named a Canada 150 Research Chair, becoming one of the younger recipients of the prestigious federal one-time grant with funding of $350,000 per year for seven years. He amassed a huge number of publications, many with surprising and influential results. He turned out to be an equally prolific fraud. The results this time weren’t, to put it in poker terms, a rare inside straight easily manipulable by nefarious forces. Trump gained ground in nearly every corner of the country, among nearly every segment of the electorate.

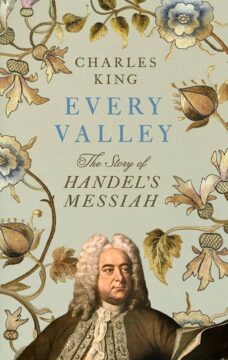

The results this time weren’t, to put it in poker terms, a rare inside straight easily manipulable by nefarious forces. Trump gained ground in nearly every corner of the country, among nearly every segment of the electorate. Does anything ever truly happen in the Messiah? This extraordinarily popular tripartite choral work, first performed in Dublin in 1742, consists almost entirely of saying rather than of doing. Circling around the redemptive power of Christ, it combines declarations with questions, prophecies, injunctions and exhortations (‘Who is this King of Glory?’, ‘Behold, I tell you a Mystery’, ‘Daughter of Sion, shout’, ‘He shall speak’). Full of urgency, tribulation and momentum, the Messiah nevertheless lacks a plot – unless we class the perennial human emotions of hope and fear, and the movement between the two, as dramatic action.

Does anything ever truly happen in the Messiah? This extraordinarily popular tripartite choral work, first performed in Dublin in 1742, consists almost entirely of saying rather than of doing. Circling around the redemptive power of Christ, it combines declarations with questions, prophecies, injunctions and exhortations (‘Who is this King of Glory?’, ‘Behold, I tell you a Mystery’, ‘Daughter of Sion, shout’, ‘He shall speak’). Full of urgency, tribulation and momentum, the Messiah nevertheless lacks a plot – unless we class the perennial human emotions of hope and fear, and the movement between the two, as dramatic action. Large numbers of

Large numbers of  Well, the most obvious answer to this question is Sally Rooney’s latest novel, Intermezzo. Every Rooney book is a major publishing event, and this latest offering—which centres on the fraught relationship between two Irish brothers—has received rave reviews almost across the board. NPR

Well, the most obvious answer to this question is Sally Rooney’s latest novel, Intermezzo. Every Rooney book is a major publishing event, and this latest offering—which centres on the fraught relationship between two Irish brothers—has received rave reviews almost across the board. NPR  Last week, technology giants Google and Amazon both unveiled deals supporting ‘advanced’ nuclear energy, as part of their efforts to become carbon-neutral.

Last week, technology giants Google and Amazon both unveiled deals supporting ‘advanced’ nuclear energy, as part of their efforts to become carbon-neutral. Even as Nehru proclaimed the moral superiority of India for taking a stance against colonialism in all forms, he oversaw India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir. In Kashmir, Nehru said, ‘democracy and morality can wait’.

Even as Nehru proclaimed the moral superiority of India for taking a stance against colonialism in all forms, he oversaw India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir. In Kashmir, Nehru said, ‘democracy and morality can wait’. I

I LAST FALL, I was rereading Resentment: A Comedy (1997) on the train on the way to a screening of Sweet Smell of Success (1957), the most perverted Hays Code movie I know, and came upon a passage I knew was coming, where a man is, to put it mildly, fisted to death by the novel’s stuttering psychopath. I began to feel physically ill. I made it through an hour of Sweet Smell before having to head home because I was still feeling ill. Probably it was just something I ate, I told myself, willfully ignoring how deeply the viciousness, the casual cruelty Indiana put on display, had scared me.

LAST FALL, I was rereading Resentment: A Comedy (1997) on the train on the way to a screening of Sweet Smell of Success (1957), the most perverted Hays Code movie I know, and came upon a passage I knew was coming, where a man is, to put it mildly, fisted to death by the novel’s stuttering psychopath. I began to feel physically ill. I made it through an hour of Sweet Smell before having to head home because I was still feeling ill. Probably it was just something I ate, I told myself, willfully ignoring how deeply the viciousness, the casual cruelty Indiana put on display, had scared me. Hadn’t it been dimming for years? Last weekend the Atlantic ran a juicy piece about the chaos and despair inside the Trump campaign. It should have reminded me more than it did at the time of the hundreds of similar articles published during his first term and during the 2024 campaign. He’s really cracking up this time, he’s lashing out at everyone in his orbit, he’s lost the thread. And then his defeat in 2020, his exile and prosecution after January 6, his increasing incoherence and paranoia, flagged even by his former staff. (“Once Top Advisers to Trump, They Now Call Him ‘Liar,’ ‘Fascist,’ and ‘Unfit’” went the title of the Times’s collection of interviews with the likes of John Kelly, James Mattis, and Mike Pence.) The pattern is so clear in retrospect: these cycles of marginalization and humiliation would have defeated anyone else, but Trump—through some combination of unprecedented luck and intuitive political genius—kept reemerging, impossible to count out no matter how outré the misdeed. Yesterday was a triumph greater than 2016. It wasn’t a fluke. Trump is America’s choice.

Hadn’t it been dimming for years? Last weekend the Atlantic ran a juicy piece about the chaos and despair inside the Trump campaign. It should have reminded me more than it did at the time of the hundreds of similar articles published during his first term and during the 2024 campaign. He’s really cracking up this time, he’s lashing out at everyone in his orbit, he’s lost the thread. And then his defeat in 2020, his exile and prosecution after January 6, his increasing incoherence and paranoia, flagged even by his former staff. (“Once Top Advisers to Trump, They Now Call Him ‘Liar,’ ‘Fascist,’ and ‘Unfit’” went the title of the Times’s collection of interviews with the likes of John Kelly, James Mattis, and Mike Pence.) The pattern is so clear in retrospect: these cycles of marginalization and humiliation would have defeated anyone else, but Trump—through some combination of unprecedented luck and intuitive political genius—kept reemerging, impossible to count out no matter how outré the misdeed. Yesterday was a triumph greater than 2016. It wasn’t a fluke. Trump is America’s choice. Political scientists have thought carefully about the kind of situation we’re in. Back in 2011, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, who just won the Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote a paper together with Ragnar Torvik titled “

Political scientists have thought carefully about the kind of situation we’re in. Back in 2011, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, who just won the Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote a paper together with Ragnar Torvik titled “