From BlackPast.org:

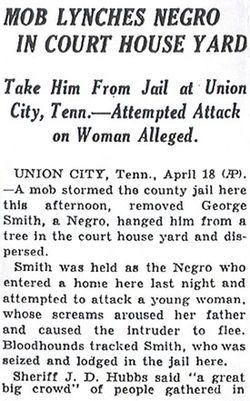

In 1931 twelve year old Thomas J. Pressley witnessed the lynching of George Smith in Union City, the county seat of Obion County, Tennessee. Now a University of Washington historian and Professor Emeritus, Dr. Pressley describes that lynching in the article below.

When I was twelve years old, I saw the body of a young black man hanging from the limb of a tree where he had been hung several hours earlier. The lynching had taken place in April, 1931, in Union City, the county seat, of Obion County, in Northwestern Tennessee, not too far from the Kentucky line to the north, and from the Mississippi River to the west. I lived in Troy, Tennessee, a town of five hundred inhabitants, ten miles. south of Union City. On the morning of April 18, 1931, a friend of mine in Troy, Hal Bennet, five or six years older than I, told me that he had to drive his car to Union City to purchase some parts for the car, and he asked if I wanted to go along for the ride. I was not old enough to drive, and I was happy to accept his invitation. Neither Hal not I had heard anything about a lynching in Union City, but when we entered town, we soon passed the Court House and saw that the grounds were filled with people and that the black man's body was hanging from the tree.

When I was twelve years old, I saw the body of a young black man hanging from the limb of a tree where he had been hung several hours earlier. The lynching had taken place in April, 1931, in Union City, the county seat, of Obion County, in Northwestern Tennessee, not too far from the Kentucky line to the north, and from the Mississippi River to the west. I lived in Troy, Tennessee, a town of five hundred inhabitants, ten miles. south of Union City. On the morning of April 18, 1931, a friend of mine in Troy, Hal Bennet, five or six years older than I, told me that he had to drive his car to Union City to purchase some parts for the car, and he asked if I wanted to go along for the ride. I was not old enough to drive, and I was happy to accept his invitation. Neither Hal not I had heard anything about a lynching in Union City, but when we entered town, we soon passed the Court House and saw that the grounds were filled with people and that the black man's body was hanging from the tree.

We were told by people in the crowd that the lynched man was in his early twenties, and that on the previous night, he had entered the bedroom and clutched the neck of a young lady prominent as a singer and pianist, the main entertainer at the new radio station recently established in Union City as the first station in Obion County. The young lady said she had fought off her attacker and severely scratched his face before he fled from her house. Within hours the sheriff and his deputy, using bloodhounds, had tracked down a black man who had scratches on his face. They then brought him before the young woman who identified him as her assailant. Convinced he had the attacker, the sheriff put him in the jail, which occupied the top floor of the Court House. Before long, however, a mob of whites gathered, broke into the jail, overpowered the sheriff and deputy, and hung the victim from the limb of the tree near the jail. I did not know the name of the black man who died that day. I was later told that he was a high school graduate which was unusual for blacks or whites in my county in that period, and that he knew the family of the woman attacked.

More here. (Note: One post throughout February will be dedicated to Black History Month.)