Jacob Heilbrunn in The National Interest:

IN JOSEPH Roth’s novel Radetzky March, Count Chojnicki drives district captain Franz von Trotta and his son Carl Joseph, a lieutenant in the Austrian infantry, in a straw-yellow britska to his small hunting lodge in the Galician forest near the border with Ukraine. After pouring glasses of 180 proof, Chojnicki disconcerts his two guests by declaring that the Habsburg Empire is doomed:

With great effort Herr von Trotta asked another question: “I don’t understand! Why shouldn’t the monarchy still exist?” “Of course,”Chojnicki answered, “taken literally, it continues to exist. We still have an army”—the count motioned to the lieutenant—“and officials”—the count pointed to the district captain. “But it is disintegrating. . . . An aged one, whose number is up, endangered by each sniffle, hangs onto his throne simply by the miracle that he can still sit upon it. How much longer, how much longer! This era doesn’t want us any longer! This era wants to create nation-states! No one believes in God. The new religion is nationalism. . . . The monarchy, our monarchy, is based on piety: in the belief that God elected the Habsburgs. . . . Our Emperor is a secular brother of the Pope. . . . The Emperor of Austria-Hungary cannot be abandoned by God. But now God has abandoned him!”

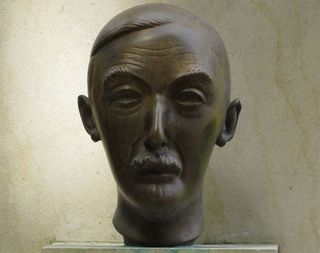

Chojnicki’s lament reflects the profound sense of abandonment that assailed not only Roth, but also his compatriot Stefan Zweig. Both mourned the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy and the loss of the comforting stability it had represented, not least for Jews like themselves. Both became refugees, going into exile years before the Anschluss, or annexation, of Austria by Nazi Germany in March 1938—in a 1933 letter, Roth warned Zweig that it was all over once Hitler had been appointed chancellor by the senescent President Hindenburg. And both ended up destroying themselves—the alcoholic Roth, dependent on handouts from Zweig, perished of delirium tremens in a Paris hospital in 1939 at the age of forty-five; Zweig, together with his young second wife, Lotte, swallowed poison in a little bungalow in 1942 in Petropolis, a lovely mountain resort located near Rio de Janeiro. Unlike Roth, however, Zweig’s literary star dimmed after his death, even though he was one of the most popular authors in the world during the 1930s, an era when books, like the cinema, could command a mass audience.

Now, in his beguiling study The Impossible Exile, George Prochnik examines Zweig’s odyssey. Prochnik, who is the author of In Pursuit of Silence, sets Zweig in the context of literary and social Vienna. It’s very much a life and times rather than a discussion of the old boy’s oeuvre, which was rather vitriolically attacked as “just putrid” by Michael Hofmann in 2010 in the London Review of Books. That his works don’t measure up to Thomas Mann’s or Roth’s almost goes without saying.

But Zweig, a compulsive collector whose possessions included Goethe’s pen and Beethoven’s desk, makes for a fascinating subject (Wes Anderson’s charming new film The Grand Budapest Hotel was inspired by him). Prochnik mines both Zweig’s memoir The World of Yesterday as well as his letters to offer numerous insights. He suggests that Zweig, who was friends with everyone from Richard Strauss to Sigmund Freud, provides an acute lens through which to examine not only the cultural contradictions of the imperial city, but also the plight of the numerous cultural émigrés from Central Europe whom Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels ridiculed as “cadavers on leave.”

More here.

Think of all the adults you know. Think of your parents and grandparents. Think of the teachers you had at school, your doctors and dentists, the people who collect your rubbish, and the actors you see on TV. All of these people probably have little mites crawling, eating, sleeping, and having sex on their faces.