Nadia Ghent at the LARB:

“THE MONTE DE PIEDAD [a pawnshop] is run like a bank, big, efficient, and clean,” Mavis Gallant writes in her diary in 1952 soon after arriving in Madrid from Montréal. “I part with my typewriter for fifteen hundred pesetas. It turns out that in this country it is the most valuable thing I own.” Gallant, ex-journalist, expatriate Canadian, is forced to choose between writing and starvation. She has left the familiarity of her North American hometown for the uncertainty of a postwar Europe struggling to return to the 20th century, the place where she intends to write fiction unfettered by assumptions about her ability to support herself as a writer. She is expected to fail, a woman alone without husband, family, or money. Still, she is intent on bowing to no one, least of all to the chorus of literary gatekeepers who believe women only want to write about cooking. She is so hungry that she faints in the street.

“THE MONTE DE PIEDAD [a pawnshop] is run like a bank, big, efficient, and clean,” Mavis Gallant writes in her diary in 1952 soon after arriving in Madrid from Montréal. “I part with my typewriter for fifteen hundred pesetas. It turns out that in this country it is the most valuable thing I own.” Gallant, ex-journalist, expatriate Canadian, is forced to choose between writing and starvation. She has left the familiarity of her North American hometown for the uncertainty of a postwar Europe struggling to return to the 20th century, the place where she intends to write fiction unfettered by assumptions about her ability to support herself as a writer. She is expected to fail, a woman alone without husband, family, or money. Still, she is intent on bowing to no one, least of all to the chorus of literary gatekeepers who believe women only want to write about cooking. She is so hungry that she faints in the street.

And yet, she has the confidence to hock the means of her livelihood, her typewriter, knowing that a market exists in the United States for her sharply drawn, realist short stories.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

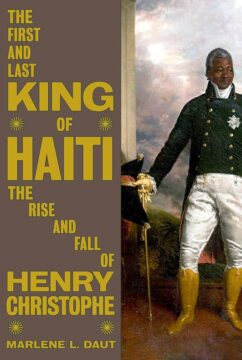

Forty years ago, most white Americans had no idea that, hard on the heels of the American and French revolutions, an enslaved population on a Caribbean island had claimed its freedom by force of arms and founded a new Black nation called Haiti. Today, Haitian revolutionary studies is an overcrowded field. Researchers have combed through acres of hard-to-find and often drastically disorganized archives, not only in Haiti and France but also in other European and Caribbean countries, and made their contents a lot more orderly and accessible than they used to be. Still, reconstructing the profile of even a fairly well-known individual from the revolutionary period can be something like deducing a whole dinosaur from a couple of toenails and teeth—a problem that confronts Marlene Daut in the writing of her exhaustive and sometime exhausting biography of Henry Christophe, the onetime king of Haiti.

Forty years ago, most white Americans had no idea that, hard on the heels of the American and French revolutions, an enslaved population on a Caribbean island had claimed its freedom by force of arms and founded a new Black nation called Haiti. Today, Haitian revolutionary studies is an overcrowded field. Researchers have combed through acres of hard-to-find and often drastically disorganized archives, not only in Haiti and France but also in other European and Caribbean countries, and made their contents a lot more orderly and accessible than they used to be. Still, reconstructing the profile of even a fairly well-known individual from the revolutionary period can be something like deducing a whole dinosaur from a couple of toenails and teeth—a problem that confronts Marlene Daut in the writing of her exhaustive and sometime exhausting biography of Henry Christophe, the onetime king of Haiti. It was in a trattoria on the Piazza Navona in early April of 1974 that for the first but not the last time I heard Gabriel García Márquez refuse to even contemplate turning his masterpiece, Cien Aňos de Soledad, into a film.

It was in a trattoria on the Piazza Navona in early April of 1974 that for the first but not the last time I heard Gabriel García Márquez refuse to even contemplate turning his masterpiece, Cien Aňos de Soledad, into a film. What makes agentic AI truly revolutionary is its architecture. While generative AI excels at processing and producing content based on patterns in its training data, agentic systems incorporate sophisticated planning modules, memory systems, and decision-making frameworks that allow them to maintain context and pursue objectives over time. They can break down complex tasks into manageable steps, prioritize actions, and even recognize when their current approach isn’t working and needs adjustment.

What makes agentic AI truly revolutionary is its architecture. While generative AI excels at processing and producing content based on patterns in its training data, agentic systems incorporate sophisticated planning modules, memory systems, and decision-making frameworks that allow them to maintain context and pursue objectives over time. They can break down complex tasks into manageable steps, prioritize actions, and even recognize when their current approach isn’t working and needs adjustment. I

I  W

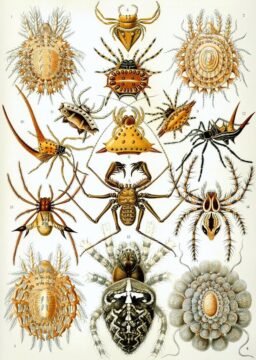

W The literature showed insects to be far more sophisticated than one might expect of an automaton. Many have nociceptors that send signals to other parts of the insect brain, such as the central complex (associated with spatial navigation and locomotion) and the mushroom bodies (linked to learning, memory, and sensory integration). Cockroaches have a nervous-system pathway that leads up from the body to the brain and back again. In a 2019 study, researchers exposed cockroaches to a hot stimulus and a neutral stimulus; the neutral stimulus prompted a weaker signal from the body to the brain, and the hot stimulus led the roaches to try and escape. (Unsettlingly, cockroaches without heads responded to the heat but did not try to escape.) A recent genomic study of mantises, which are notorious for eating their mates during and after sex, found genes that code for nociceptive ion channels—proteins that respond to pain.

The literature showed insects to be far more sophisticated than one might expect of an automaton. Many have nociceptors that send signals to other parts of the insect brain, such as the central complex (associated with spatial navigation and locomotion) and the mushroom bodies (linked to learning, memory, and sensory integration). Cockroaches have a nervous-system pathway that leads up from the body to the brain and back again. In a 2019 study, researchers exposed cockroaches to a hot stimulus and a neutral stimulus; the neutral stimulus prompted a weaker signal from the body to the brain, and the hot stimulus led the roaches to try and escape. (Unsettlingly, cockroaches without heads responded to the heat but did not try to escape.) A recent genomic study of mantises, which are notorious for eating their mates during and after sex, found genes that code for nociceptive ion channels—proteins that respond to pain. As the first ever memoir by a sitting pope, Hope is a publisher’s dream, with a rich backstory culminating in Francis’s election in 2013. It recounts how, as Jorge Bergoglio, grandchild of Italian immigrants to Argentina, he grew up in a sprawling family, loved football and the tango (which he calls “an emotional, visceral dialogue that comes from afar, from ancient roots”), studied chemistry, then joined the Jesuit order and became a priest. After dallying with Peronism and enduring the Argentinian junta, he became the cardinal archbishop of Buenos Aires. Then, just as he was planning his retirement, Benedict XVI resigned and he was chosen as his successor.

As the first ever memoir by a sitting pope, Hope is a publisher’s dream, with a rich backstory culminating in Francis’s election in 2013. It recounts how, as Jorge Bergoglio, grandchild of Italian immigrants to Argentina, he grew up in a sprawling family, loved football and the tango (which he calls “an emotional, visceral dialogue that comes from afar, from ancient roots”), studied chemistry, then joined the Jesuit order and became a priest. After dallying with Peronism and enduring the Argentinian junta, he became the cardinal archbishop of Buenos Aires. Then, just as he was planning his retirement, Benedict XVI resigned and he was chosen as his successor.

After Donald Trump was first elected, the same political scientists who had adamantly insisted that he could never win a presidential election quickly coalesced on the same interpretation of his success. He was an authoritarian populist who cleaved the electorate into “real” Americans and everybody else, promising to put the former in charge while banishing the latter to the margins (or, according to the more extreme alarmists, putting them in camps). On this interpretation, two things were intrinsically linked: Trump’s demagogic talent for mobilizing popular opinion against the norms and values of a deeply mistrusted establishment; and his apparent alliance with a predominantly white and elderly electorate that had experienced a decline in their social status, feared the future, and was ready to resist change by any means necessary.

After Donald Trump was first elected, the same political scientists who had adamantly insisted that he could never win a presidential election quickly coalesced on the same interpretation of his success. He was an authoritarian populist who cleaved the electorate into “real” Americans and everybody else, promising to put the former in charge while banishing the latter to the margins (or, according to the more extreme alarmists, putting them in camps). On this interpretation, two things were intrinsically linked: Trump’s demagogic talent for mobilizing popular opinion against the norms and values of a deeply mistrusted establishment; and his apparent alliance with a predominantly white and elderly electorate that had experienced a decline in their social status, feared the future, and was ready to resist change by any means necessary. Unknowability was everywhere, not just in my interactions with people, but in the life and world I was eagerly observing. One morning early, maybe five a.m., I woke in a one-room shack of boards with a dirt floor and a thatched roof. It was raining. I had no bed; slept on a pallet. The thatch leaked, making the floor a muddy lake whose shore brushed my pallet.

Unknowability was everywhere, not just in my interactions with people, but in the life and world I was eagerly observing. One morning early, maybe five a.m., I woke in a one-room shack of boards with a dirt floor and a thatched roof. It was raining. I had no bed; slept on a pallet. The thatch leaked, making the floor a muddy lake whose shore brushed my pallet.