Sean Carroll at Preposterous Universe:

A typical human lifespan is approximately three billion heartbeats in duration. Lasting that long requires not only intrinsic stability, but an impressive capacity for self-repair. Nevertheless, things do occasionally break down, and cancer is one of the most dramatic examples of such breakdown. Given that the body is generally so good at protecting itself, can we harness our internal security patrol – the immune system – to fight cancer? This is the hope of Nobel Laureate James Allison, who works on studying the structure and behavior of immune cells, and ways to coax them into fighting cancer. This approach offers hope of a way to combat cancer effectively, lastingly, and in a relatively gentle way.

A typical human lifespan is approximately three billion heartbeats in duration. Lasting that long requires not only intrinsic stability, but an impressive capacity for self-repair. Nevertheless, things do occasionally break down, and cancer is one of the most dramatic examples of such breakdown. Given that the body is generally so good at protecting itself, can we harness our internal security patrol – the immune system – to fight cancer? This is the hope of Nobel Laureate James Allison, who works on studying the structure and behavior of immune cells, and ways to coax them into fighting cancer. This approach offers hope of a way to combat cancer effectively, lastingly, and in a relatively gentle way.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

There are certain places in the world where the boundaries between past and present seem porous, almost arbitrary. The air is cool and quiet in the mornings on the Knepp estate in Sussex, England — quiet, that is, except for the lilt of birdsong and the rumbling beat of hooves. The landscape is one of fields and copses, of dense, tangled shrubbery and shifting, murky pools. The green sward is low and neatly cropped, churned up in many places by the tread of heavy animals. The decade is the 2020s, but it might as well be the 1820s — or a far more ancient era yet. A woman gazing out over the Knepp estate one misty morning might imagine herself looking over a medieval common, or even a vista out of the long-lost Neolithic, and her intuition would not be much wrong. Yet at Knepp, of all places, this deep sense of antiquity is an illusion.

There are certain places in the world where the boundaries between past and present seem porous, almost arbitrary. The air is cool and quiet in the mornings on the Knepp estate in Sussex, England — quiet, that is, except for the lilt of birdsong and the rumbling beat of hooves. The landscape is one of fields and copses, of dense, tangled shrubbery and shifting, murky pools. The green sward is low and neatly cropped, churned up in many places by the tread of heavy animals. The decade is the 2020s, but it might as well be the 1820s — or a far more ancient era yet. A woman gazing out over the Knepp estate one misty morning might imagine herself looking over a medieval common, or even a vista out of the long-lost Neolithic, and her intuition would not be much wrong. Yet at Knepp, of all places, this deep sense of antiquity is an illusion. W

W THIS book made me, by turn, wince, squirm, smile wryly, and gasp in surprise and in horror. It is not for the fainthearted. King has produced a comprehensive and detailed historical account of the way in which four different parts of women’s bodies — breasts, clitoris, hymen, and womb — have been viewed, interpreted, and treated, by society, medicine, and the Church, and mainly by men. She reaches back into classical times and around the globe to other than Western civilisations.

THIS book made me, by turn, wince, squirm, smile wryly, and gasp in surprise and in horror. It is not for the fainthearted. King has produced a comprehensive and detailed historical account of the way in which four different parts of women’s bodies — breasts, clitoris, hymen, and womb — have been viewed, interpreted, and treated, by society, medicine, and the Church, and mainly by men. She reaches back into classical times and around the globe to other than Western civilisations. One of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s remarkable early accomplishments was the long poem that lent its title to his 1961 collection of poetry, La Religione del mio tempo, or “The Religion of My Time.” And while religion was many things to Pasolini, what he was most religiously devoted to might have been the idea of being of his time. His writing—whether in the form of poetry, fiction or polemic, among which he passionately blurred the distinctions—staked a great deal on immediacy. In this sense it was close to speech: an intervention in the moment as much as a message for futurity.

One of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s remarkable early accomplishments was the long poem that lent its title to his 1961 collection of poetry, La Religione del mio tempo, or “The Religion of My Time.” And while religion was many things to Pasolini, what he was most religiously devoted to might have been the idea of being of his time. His writing—whether in the form of poetry, fiction or polemic, among which he passionately blurred the distinctions—staked a great deal on immediacy. In this sense it was close to speech: an intervention in the moment as much as a message for futurity. Let’s call the student R. The principal of the school I was visiting said to others in the room soon after I arrived in her office, “Where is R.? Oh, he has a story to tell you.”

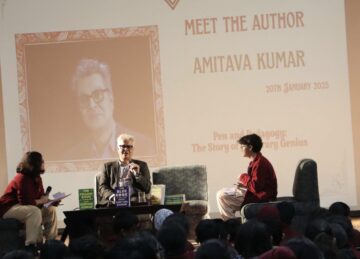

Let’s call the student R. The principal of the school I was visiting said to others in the room soon after I arrived in her office, “Where is R.? Oh, he has a story to tell you.” Scientists have long known that DNA-copying systems make the occasional blunder — that’s how cancers often start — but only in recent years has technology been sensitive enough to catalog every genetic booboo. And it’s revealed we’re riddled with errors. Every human being is a vast mosaic of cells that are mostly identical, but different here or there, from one cell or group of cells to the next.

Scientists have long known that DNA-copying systems make the occasional blunder — that’s how cancers often start — but only in recent years has technology been sensitive enough to catalog every genetic booboo. And it’s revealed we’re riddled with errors. Every human being is a vast mosaic of cells that are mostly identical, but different here or there, from one cell or group of cells to the next. Washington is filled with lobbying offices and fund-raisers because powerful interests believe something is gained when dollars are spent. They are right. We have come to expect and accept a grotesque level of daily corruption in American politics — abetted by a series of Supreme Court rulings that give money the protections of speech and by congressional Republicans who have fought even modest campaign finance reforms. But we have at least some rules to limit money’s power in politics and track its movements.

Washington is filled with lobbying offices and fund-raisers because powerful interests believe something is gained when dollars are spent. They are right. We have come to expect and accept a grotesque level of daily corruption in American politics — abetted by a series of Supreme Court rulings that give money the protections of speech and by congressional Republicans who have fought even modest campaign finance reforms. But we have at least some rules to limit money’s power in politics and track its movements. We all know that time seems to pass at different speeds in different situations. For example, time appears to go slowly when we travel to unfamiliar places. A week in a foreign country seems much longer than a week at home. Time also seems to pass slowly when we are bored or

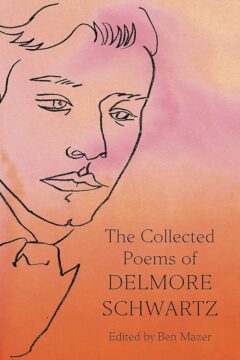

We all know that time seems to pass at different speeds in different situations. For example, time appears to go slowly when we travel to unfamiliar places. A week in a foreign country seems much longer than a week at home. Time also seems to pass slowly when we are bored or Every sentence of “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” was elegant and foreboding. The mother is having second thoughts; the father is exaggerating his fortune. Delusions of grandeur, and Delmore hasn’t even been conceived. There is no affection here. Regrets only.

Every sentence of “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” was elegant and foreboding. The mother is having second thoughts; the father is exaggerating his fortune. Delusions of grandeur, and Delmore hasn’t even been conceived. There is no affection here. Regrets only. Confusion and anxiety is rippling through the US health-research community this week following

Confusion and anxiety is rippling through the US health-research community this week following  THE EDITORS OF VERGE Books, Peter O’Leary and John Tipton, continue to lavish love on books wholly deserving of the care. Take Joseph Donahue’s two-volume Terra Lucida XIII–XXI (2024) as the most current example: Musica Callada and Near Star come housed in a box clad in a deep-loam brown cloth, the color of leaf-rot, fungal fecundity itself. Such care, if it’s truly meaningful, is so only because it adorns a poetry whose nature shares the same cosmic ethic. Joseph Donahue is a poet for whom, couplet by couplet, poetry is the principal way of tuning a life to the deeper orders of the world, where even death’s irreparable rift is a complement to life’s wild loveliness. For Donahue, the poem is the primary tool for understanding the weird work living is.

THE EDITORS OF VERGE Books, Peter O’Leary and John Tipton, continue to lavish love on books wholly deserving of the care. Take Joseph Donahue’s two-volume Terra Lucida XIII–XXI (2024) as the most current example: Musica Callada and Near Star come housed in a box clad in a deep-loam brown cloth, the color of leaf-rot, fungal fecundity itself. Such care, if it’s truly meaningful, is so only because it adorns a poetry whose nature shares the same cosmic ethic. Joseph Donahue is a poet for whom, couplet by couplet, poetry is the principal way of tuning a life to the deeper orders of the world, where even death’s irreparable rift is a complement to life’s wild loveliness. For Donahue, the poem is the primary tool for understanding the weird work living is.