Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Dario Amodei On DeepSeek and Export Controls

Dario Amodei, CEO Anthropic, at his own website:

A few weeks ago I made the case for stronger US export controls on chips to China. Since then DeepSeek, a Chinese AI company, has managed to — at least in some respects — come close to the performance of US frontier AI models at lower cost.

A few weeks ago I made the case for stronger US export controls on chips to China. Since then DeepSeek, a Chinese AI company, has managed to — at least in some respects — come close to the performance of US frontier AI models at lower cost.

Here, I won’t focus on whether DeepSeek is or isn’t a threat to US AI companies like Anthropic (although I do believe many of the claims about their threat to US AI leadership are greatly overstated). Instead, I’ll focus on whether DeepSeek’s releases undermine the case for those export control policies on chips. I don’t think they do. In fact, I think they make export control policies even more existentially important than they were a week ago.

Export controls serve a vital purpose: keeping democratic nations at the forefront of AI development. To be clear, they’re not a way to duck the competition between the US and China. In the end, AI companies in the US and other democracies must have better models than those in China if we want to prevail. But we shouldn’t hand the Chinese Communist Party technological advantages when we don’t have to.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Immunity Engineer

Veronique Greenwood in Harvard Magazine:

One story David Mooney tells starts with a slug. “This slug does a really good job of creating a mucus that allows it to stick really tightly, so predators can’t just peel it off and eat it,” he says. The mucus, a marvelous material, turns out to consist of a springy mesh made of sugars and proteins threaded through each other. When pushed with a finger, the energy disperses through the mesh, rather than tearing it, indicating serious toughness. There’s plenty of water in there, too, Mooney points out. That’s handy, because if you want a substance to stick to your inner organs, it’s more convenient if you know it can withstand the damp.

One story David Mooney tells starts with a slug. “This slug does a really good job of creating a mucus that allows it to stick really tightly, so predators can’t just peel it off and eat it,” he says. The mucus, a marvelous material, turns out to consist of a springy mesh made of sugars and proteins threaded through each other. When pushed with a finger, the energy disperses through the mesh, rather than tearing it, indicating serious toughness. There’s plenty of water in there, too, Mooney points out. That’s handy, because if you want a substance to stick to your inner organs, it’s more convenient if you know it can withstand the damp.

Mooney is not a slug biologist. He is in fact the Pinkas Family professor of bioengineering, a founding faculty member of Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and the holder of numerous patents on subjects ranging from recipes for cancer vaccines to ways to guide drugs through the body (see “Fighting Disease in Situ,” May-June 2009, page 10, and “Biological Vaccine Factories,” January-February 2021, page 9). But he is a strong proponent of observation. One researcher in his lab realized that the slug mucus strongly resembled material another group member had been exploring some years before.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Your Gut Microbiome Might Be Ruining Your Health. Here’s How to Fix It

Sammi Caramela in Vice:

Did you know your gut microbiome can impact various aspects of your health—including your mental and emotional well-being? A healthier biome means a healthier you, and according to professionals, all it takes is a few simple lifestyle changes. Cleveland Clinic defines a gut microbiome as “a microscopic world within the world of your larger body. The trillions of microorganisms that live there affect each other and their environment in various ways. They also appear to influence many aspects of your overall health, both within your digestive system and outside of it.” Basically, your gut has its own biome filled with microscopic organisms, bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. And when there’s a disruption in the balance of good and bad organisms within your gut, you can experience a ton of concerning health issues.

Did you know your gut microbiome can impact various aspects of your health—including your mental and emotional well-being? A healthier biome means a healthier you, and according to professionals, all it takes is a few simple lifestyle changes. Cleveland Clinic defines a gut microbiome as “a microscopic world within the world of your larger body. The trillions of microorganisms that live there affect each other and their environment in various ways. They also appear to influence many aspects of your overall health, both within your digestive system and outside of it.” Basically, your gut has its own biome filled with microscopic organisms, bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. And when there’s a disruption in the balance of good and bad organisms within your gut, you can experience a ton of concerning health issues.

Doctors at UCLA Health recommend, first and foremost, focusing on eating whole foods, exercising, spending time outdoors, getting sufficient sleep, and managing stress.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Luna Moth

Pale green and pressed against the window screen,

shot through with field, you watch nighttime’s corners

curl with four white eyes, your under-self unfurled

to my one room of word—kettle, counter,

knife block. Having lived one of your life’s

six nights, you leave a limp silhouette where you

left off—let me be the creature circling

your sleep. I am the most benign unknown;

I do not touch. With what nights are left, plant

your wing beat in my sleep, be the only

hovering thing. If only you could teach me

survival without sustenance, unworried

love, how to find oneself at a window

one morning and think nothing of what happens next

Cecily Parks

from Blackbird

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Narrative Wisdom In A Fragmented World

Alexander Stern at The Hedgehog Review:

But the problem with advice is not conceptual. Atwood’s disappointed acolytes were hoping not for a kind of guidance that is analytically impossible but for one that is merely in severe decline.

But the problem with advice is not conceptual. Atwood’s disappointed acolytes were hoping not for a kind of guidance that is analytically impossible but for one that is merely in severe decline.

The German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller,” nominally about the Russian short-story writer Nikolai Leskov, offers a historical reason for this decline: “the communicability of experience is decreasing.” Benjamin tries to get at this shift by way of the decline of storytelling. Storytellers like Leskov, Franz Kafka, and Edgar Allan Poe write in a way that approximates the oral tradition. Their stories are still “woven into the fabric of real life,” and they contain, “openly or covertly, something useful,” whether it is moral, practical, or proverbial. Benjamin gives an example of a story from Herodotus about the Egyptian king Psammenitus, who is defeated and captured by the Persians and forced to watch as his son and daughter are marched toward death or enslavement as part of the Persian victory procession. Psammenitus is unmoved, “his eyes fixed on the ground,” until he recognizes among the prisoners one of his servants—“an old, impoverished man.” Only then does “he beat his fists against his head and [give] all the signs of deepest mourning.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Other Side of Sherman’s March

Scott Spillman at The New Yorker:

The second hour of “Gone with the Wind,” the bold, almost brazenly romantic Civil War epic that won ten Academy Awards, is largely a portrait of hell. “The skies rained death,” the screen reads. General William Tecumseh Sherman and his Union Army have brutally taken Atlanta during a hard-fought campaign, at a combined cost of nearly seventy-five thousand casualties. Scarlett O’Hara, a wealthy white Southerner, picks her way out of the city, passing the littered remains of wagons and men while vultures hover overhead. All the plantation houses she sees have been reduced to charred ruins.

The second hour of “Gone with the Wind,” the bold, almost brazenly romantic Civil War epic that won ten Academy Awards, is largely a portrait of hell. “The skies rained death,” the screen reads. General William Tecumseh Sherman and his Union Army have brutally taken Atlanta during a hard-fought campaign, at a combined cost of nearly seventy-five thousand casualties. Scarlett O’Hara, a wealthy white Southerner, picks her way out of the city, passing the littered remains of wagons and men while vultures hover overhead. All the plantation houses she sees have been reduced to charred ruins.

Only her own plantation has survived Sherman’s assault. Scarlett opens the door to find her father, but it’s clear from his blank eyes that he’s a broken man. The house, too, is a mere shell of itself. The Yankees used it as a headquarters, and they stole everything they didn’t burn: livestock, clothes, rugs, even Scarlett’s mother’s rosaries. The slaves, too, are gone—only three out of a hundred are left. Scarlett, starving, staggers behind the house and tries to eat radishes from the ground, searching for whatever scraps of food remain.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, January 29, 2025

The short, blazing life of Italian philosopher Pico della Mirandola

Dennis Duncan in The Guardian:

Of all the great intellectuals of the Renaissance, Pico della Mirandola is surely the most personally captivating. “He wins one on,” as the Victorian essayist Walter Pater put it, his life having “some touch of sweetness in it”. An Italian aristocrat who dabbled in magic and escaped from prison after eloping with the wife of a Medici lord, his books were burned on the orders of the pope. Edward Wilson-Lee’s new biography brings us the events of Pico’s short, blazing life, but also what is most strange and attractive about him: the wonder of a scholar who felt himself on the verge of being able to commune with angels.

Of all the great intellectuals of the Renaissance, Pico della Mirandola is surely the most personally captivating. “He wins one on,” as the Victorian essayist Walter Pater put it, his life having “some touch of sweetness in it”. An Italian aristocrat who dabbled in magic and escaped from prison after eloping with the wife of a Medici lord, his books were burned on the orders of the pope. Edward Wilson-Lee’s new biography brings us the events of Pico’s short, blazing life, but also what is most strange and attractive about him: the wonder of a scholar who felt himself on the verge of being able to commune with angels.

The basic facts are straightforward. Born in northern Italy in 1463, he was a child prodigy with astonishing powers of memory. (He is said to have been able to recite the whole of Dante’s Divine Comedy backwards.) The story of Pico’s education has something of the feel of a video game, a tour through the great universities of Europe – Bologna, Ferrara, Padua, Paris – completing some branch of knowledge – law, medicine, the classical languages – before moving on to the next level.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Will bird flu spark a human pandemic? Scientists say the risk is rising

Max Kozlov in Nature:

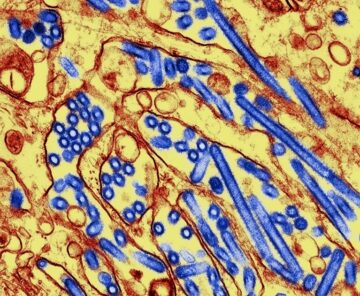

Ten months on from the shocking discovery that a virus usually carried by wild birds can readily infect cows, at least 68 people in North America have become ill from the pathogen and one person has died.

Ten months on from the shocking discovery that a virus usually carried by wild birds can readily infect cows, at least 68 people in North America have become ill from the pathogen and one person has died.

Although many of the infections have been mild, emerging data indicate that variants of the avian influenza virus H5N1 that are spreading in North America can cause severe disease and death, especially when passed directly to humans from birds. The virus is also adapting to new hosts — cows and other mammals — raising the risk that it could spark a human pandemic.

“The risk has increased as we’ve gone on — especially in the last couple of months, with the report of [some] severe infections,” says Seema Lakdawala, an influenza virologist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

Last week, US President Donald Trump took office and announced that he will pull the United States — where H5N1 is circulating in dairy cows — out of the World Health Organization, the agency that coordinates the global response to health emergencies. This has sounded alarm bells among researchers worried about bird flu.

Here, Nature talks to infectious-disease specialists about what they’re learning about how humans get sick from the virus, and the chances of a bird-flu pandemic.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Mutual Funds Shape Society

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Most Important Time in History Is Now

Tomas Pueyo at Uncharted Territories:

AI is progressing so fast that its researchers are freaking out. It is now routinely more intelligent than humans, and its speed of development is accelerating. New developments from the last few weeks have accelerated it even more. Now, it looks like AIs can be more intelligent than humans in 1-5 years, and intelligent like gods soon after. We’re at the precipice, and we’re about to jump off the cliff of AI superintelligence1, whether we want to or not…

Six months ago, I wrote What Would You Do If You Had 8 Years Left to Live?, where I explained that the market predicted Artificial General Intelligence (AGI, an AI capable of doing what most humans can do) eight years later, by 2032. Since then, that date has been pulled forward. It’s now predicted to arrive in just six years, so six months were enough to pull the date forward by one year. Odds now looks like this:

But AI that matches human intelligence is not the most concerning milestone. The most concerning one is ASI, Artificial SuperIntelligence: an intelligence so far beyond human capabilities that we can’t even comprehend it.

According to forecasters, that will come in five years…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Shift to Vibes: The Birth of a Retarded Avant-Garde

John Ganz in Unpopular Front:

…As for putting on the airs of religion and spirituality, this is probably both the saddest and desperate pose of all and one, if you are a believer, that perilously approaches blasphemy in its violation of the 3rd commandment: “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.”No wonder then that despite all the holy muttering there is no hint of the pathos and depth that can be conveyed by genuine religious art and sentiment even to sensitive non-believers. It is more spiritually sterile than the secular world it reviles.

…As for putting on the airs of religion and spirituality, this is probably both the saddest and desperate pose of all and one, if you are a believer, that perilously approaches blasphemy in its violation of the 3rd commandment: “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.”No wonder then that despite all the holy muttering there is no hint of the pathos and depth that can be conveyed by genuine religious art and sentiment even to sensitive non-believers. It is more spiritually sterile than the secular world it reviles.

So far I’ve skirted the question of politics, namely whether or not there is an incipient fascism here. The scene does in fact represent aa similar sort of petulant, nihilistic petty-bourgeois rebellion, the simultaneous adoption of the aesthetics of cutting-edge modernity and nostalgic yearning for a more wholesome pre-modern past, a fascination with cruelty, the mob, and extreme violence, and a general vulgar cult of doom and decadence that characterized fascist avant-gardes between the wars but I think it’s all too slight, lazy, parochial and self-centered to desire to plunge itself into an anonymous upsurge of a totalitarian movement’s mass energy. Occasional moods of self-destruction notwithstanding, these are not the cultural shock troops. In fact, to say they are fascist adds too much to their cachet, to all the hocus-pocus, working as a form of negative P.R. The myths surrounding fascism still suggests something dangerous and powerful in the public mind, rather than reflecting its historical reality: a stupid and pathetic hysterical outburst of the mediocre and banal.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Dark proteins’ hiding in our cells could hold clues to cancer and other diseases

Ewen Callaway in Nature:

In 2009, Jonathan Weissman was hunting for a new way to spy on what happens inside a cell. In particular, the molecular cell biologist wanted to know what proteins are produced at any given moment. So his laboratory came up with a way to directly measure the output of ribosomes — the cell’s protein factories.

In 2009, Jonathan Weissman was hunting for a new way to spy on what happens inside a cell. In particular, the molecular cell biologist wanted to know what proteins are produced at any given moment. So his laboratory came up with a way to directly measure the output of ribosomes — the cell’s protein factories.

The method, developed with then-postdoc Nicholas Ingolia, who is now at the University of California, Berkeley, involves collecting all of a cells’ ribosomes and sequencing the individual strands of messenger RNA that are bound to them. The researchers hoped this tool, called ribosome profiling, would provide an accurate tally of all the proteins a cell makes and their relative quantities.

But, when Weissman and others began trying the method out, they turned up a giant surprise. Not only were ribosomes busily churning out proteins encoded by known genes in a cell’s genome, but they also seemed to be making thousands upon thousands of ‘dark proteins’ that map to portions of the genome that weren’t thought to produce proteins1. “That was the ‘Aha!’ moment for us,” says Weissman, who is based at the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Soon, his lab and others were uncovering unexpected translation events in nearly every organism they examined.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nosferatu (2024) – Against Tradwives and Uplift Stories

J.M. Tyree at Film International:

Robert Eggers’s new version of Nosferatu is not my favorite contemporary vampire movie (that would have to be Ana Lily Amipour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night [2014]), or even my favorite Eggers film. The Lighthouse (2019), an extraordinary and idiosyncratic nightmare, is probably more true to Murnau’s Expressionist ideals, and the sublime potential of the Gothic, than this remake. For the first hour I didn’t know why Nosferatu was being remade at all – surely this was a mistaken project from the beginning since Murnau’s inimitable 1922 classic remains incorruptible from beyond the grave. As the second half of the film unfolded into abject madness, and afterwards thinking through the film with friends, however, Eggers’s Nosferatu has stayed with me, its shadows deepening as its various challenges to its predecessors have seeped into the frame.

Robert Eggers’s new version of Nosferatu is not my favorite contemporary vampire movie (that would have to be Ana Lily Amipour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night [2014]), or even my favorite Eggers film. The Lighthouse (2019), an extraordinary and idiosyncratic nightmare, is probably more true to Murnau’s Expressionist ideals, and the sublime potential of the Gothic, than this remake. For the first hour I didn’t know why Nosferatu was being remade at all – surely this was a mistaken project from the beginning since Murnau’s inimitable 1922 classic remains incorruptible from beyond the grave. As the second half of the film unfolded into abject madness, and afterwards thinking through the film with friends, however, Eggers’s Nosferatu has stayed with me, its shadows deepening as its various challenges to its predecessors have seeped into the frame.

Something interesting about the stakes of filmed adaptation are at play in this film, because it’s largely an adaptation of another film and not of an “original” literary property. Even in its relatively routine first half, the film is remarkably faithful to Murnau’s faithless adaptation of Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Stoker’s widow successfully sued for copyright infringement, and, although the film outlived its legal death, the 1922 Nosferatu remains a founding document of the concept of intellectual property in cinema. Yet if Nosferatu has always been about IP, then the endless revenants of the ever-proliferating vampire mythos are also about cinematic DNA, and whose ideas are grafted on to new branches of the story of the hungry undead.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Home Alone

Light flooded through the stair-landing window,

fired the cut glass candy dish, and broke into colors

across the low bookcase. Home alone,

that itself enough rapture, but now this worldly joy.

I remember trying to remember it, fix it, make it stay

— what was I, ten? eleven? —so beautiful.

I knew it could not last, but hoped its memory would.

by Nils Peterson

from Finding the Way To One’s Self

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Miłosz, Camus, Einstein, and Weil

Cynthia Haven at Church Life Journal:

Beavers were hunted to near extinction in Europe by mid-century, but in America, they thrived. For the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, they would have held an obvious fascination. They are muscular animals; they can carry their own substantial weight when building a lodge, which can total three tons. And though they are, to all appearances, dumpy, heavy rodents, when they plunge into water, they are as sleek as otters. One of these odd creatures moved Miłosz to make perhaps the most significant decision of his life, though he would see that only in retrospect. He would write about it years later in France—but he was far from Paris on that day, on one early winter morning before dawn in the winter of 1948-49.

Beavers were hunted to near extinction in Europe by mid-century, but in America, they thrived. For the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, they would have held an obvious fascination. They are muscular animals; they can carry their own substantial weight when building a lodge, which can total three tons. And though they are, to all appearances, dumpy, heavy rodents, when they plunge into water, they are as sleek as otters. One of these odd creatures moved Miłosz to make perhaps the most significant decision of his life, though he would see that only in retrospect. He would write about it years later in France—but he was far from Paris on that day, on one early winter morning before dawn in the winter of 1948-49.

The love and reverence many Californians feel for the Pacific is, in much of the world, directed towards rivers. Certainly, it was so with Miłosz. He had been drawn to rivers since his childhood, on the Niewiaża river, in Lithuania’s Šeteniai, and now he was unimaginably far away, in the land where natura ruled supreme. The Pacific Ocean that was his destined home was terrifying and alien, but this river was manageable.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, January 28, 2025

Where the Wild Things Aren’t

Agnes Callard in Asterisk Magazine:

Other than fairy tales — which were, by and large, originally compiled for adult audiences — children’s literature from the past holds little of interest for children today. Consider one of the earliest known examples of a book targeted at children, James Janeway’s A Token for Children from 1671. A typical story in this collection tells us how young a child was when he memorized the catechism, how passionately he cared for the souls of his brothers and sisters, and how obedient and respectful he was with his elders. It might quote at length from one of his prayers and end by describing his peaceful death from the plague at the age of 10. Every story in Token ends in this way, with a boy or girl rewarded for his or her piety with a happy early death.

Other than fairy tales — which were, by and large, originally compiled for adult audiences — children’s literature from the past holds little of interest for children today. Consider one of the earliest known examples of a book targeted at children, James Janeway’s A Token for Children from 1671. A typical story in this collection tells us how young a child was when he memorized the catechism, how passionately he cared for the souls of his brothers and sisters, and how obedient and respectful he was with his elders. It might quote at length from one of his prayers and end by describing his peaceful death from the plague at the age of 10. Every story in Token ends in this way, with a boy or girl rewarded for his or her piety with a happy early death.

Things do loosen up a bit over the next century, but narrative fiction directed at children in the 1700s and early 1800s still tends to be heavily didactic and moralistic, featuring stylized descriptions of children inhabiting not a social and political reality but an abstract, idealized world of moral instruction — instruction that they, in turn, receive gladly and obediently. Children today would not know what to make of it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Inside Anthropic’s Race to Build a Smarter Claude and Human-Level AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

DeepSeek: everything you need to know right now

Azeem Azhar at Exponential View:

My WhatsApp exploded over the weekend as we received an early Chinese New Year surprise from DeepSeek. The Chinese AI firm launched its reasoning model last week, and analysts belatedly woke up to it. The firm’s consumer app jumped to number 1 in the Apple AppStore and American stock markets, overly indexed on big tech, are taking a pounding.

My WhatsApp exploded over the weekend as we received an early Chinese New Year surprise from DeepSeek. The Chinese AI firm launched its reasoning model last week, and analysts belatedly woke up to it. The firm’s consumer app jumped to number 1 in the Apple AppStore and American stock markets, overly indexed on big tech, are taking a pounding.

We’ve been tracking DeepSeek for a while. I first wrote about it all the way back in EV#451 in Dec 2023, with the question: “Is China the new open-source leader?”.

And last month when writing about DeepSeek V3, I wrote:

The gap between open source (like DeepSeek) and closed source (like OpenAI) is narrowing rapidly. It calls into question efforts to constrain open-source AI development… The elegance of the approach, more refined than brute force, ought to be a wake-up call for US labs following a ‘muscle-car’ strategy.

It was, I said back in December 2024, “the ‘Chinese Sputnik’ that demands our attention”.

There are many significant ramifications from the R-1 release and the response to it: ramifications on geopolitics, the speed of AI adoption and, if you hold any of your assets in the Nasdaq, on your own personal wealth.

At the time of writing, about $1.2 trillion has been wiped off the US markets, led of Nvidia getting a hammering.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.