Ashley Smart in Undark:

In the summer of 2022, Abdel Abdellaoui was set to give a keynote at the annual conference of the International Society for Intelligence Research. But when he learned he’d be sharing a speaker roster with Emil Kirkegaard, Abdellaoui announced on Twitter that he was cancelling his lecture.

In the summer of 2022, Abdel Abdellaoui was set to give a keynote at the annual conference of the International Society for Intelligence Research. But when he learned he’d be sharing a speaker roster with Emil Kirkegaard, Abdellaoui announced on Twitter that he was cancelling his lecture.

Kirkegaard is perhaps best known for his provocative writing on genetics and race. On his blog, he has asserted that Black Americans are less honest and less intelligent than their White counterparts; that affirmative action produces Black and Hispanic doctors who kill people with their incompetence; that Africans are excessively predisposed to violence; and that the hereditarian hypothesis of intelligence — roughly, the idea that races or ancestry groups differ in average intelligence in ways that are substantially attributable to genetics — is “almost certainly true.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The origins of Eid can be traced back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. Eid al-Fitr, which translates to the “Festival of Breaking the Fast,” is celebrated at the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting. The significance of this festival lies in the completion of a month-long spiritual journey of self-discipline, reflection, and devotion to Allah. It is a time for Muslims to express gratitude for the strength and patience shown during Ramadan. The celebration of Eid al-Fitr is not only a personal milestone but also a communal event that reinforces the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood among Muslims.

The origins of Eid can be traced back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. Eid al-Fitr, which translates to the “Festival of Breaking the Fast,” is celebrated at the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting. The significance of this festival lies in the completion of a month-long spiritual journey of self-discipline, reflection, and devotion to Allah. It is a time for Muslims to express gratitude for the strength and patience shown during Ramadan. The celebration of Eid al-Fitr is not only a personal milestone but also a communal event that reinforces the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood among Muslims.

“People give estimates of what they think we’re making, and it’s always way low,” he told me from the plush interior of his Rolls-Royce, which was still scented with a synthetic new-purchase aroma. “Our watch hours on YouTube [in December] were, like, 5.7 million hours. And there’s a commercial every 10 minutes.”

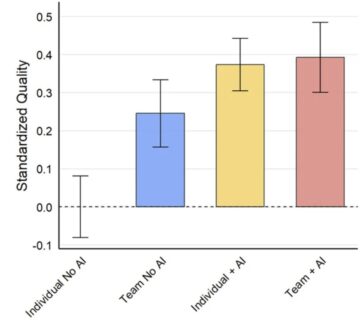

“People give estimates of what they think we’re making, and it’s always way low,” he told me from the plush interior of his Rolls-Royce, which was still scented with a synthetic new-purchase aroma. “Our watch hours on YouTube [in December] were, like, 5.7 million hours. And there’s a commercial every 10 minutes.” Over the past couple years, we have learned that AI can boost the productivity of individual knowledge workers ranging from

Over the past couple years, we have learned that AI can boost the productivity of individual knowledge workers ranging from  Political scientists

Political scientists  S

S Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read. Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania.

Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania. Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have.

Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have. “Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England.

“Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England.