Yongyi Min in Nature:

As I sat down to read David Spiegelhalter’s The Art of Uncertainty, much of the world’s focus was on the 2024 US presidential elections. Forecasts flooded news outlets and social media, saying that the race was too close to call. When the results came out — a resounding win for Donald Trump — they laid bare the limitations of predictive models, which are subject to assumptions, uncertainty and shifts in voter behaviour. It was ideal timing, it turned out, for reading a book that emphasizes the importance of humility when dealing with uncertainty and predictions.

Spiegelhalter, a renowned statistician, has crafted a masterful examination of how to understand, measure and communicate uncertainty. His great ability to translate complex statistical concepts into accessible language is fully on display. Drawing from decades of experience, he neatly weaves together historical anecdotes, real-world examples and rigorous statistical analyses to provide a comprehensive overview.

This book asks how we can use data and statistical analysis to make informed decisions in the face of uncertainty. It equips readers with the tools to think critically about risk and chance, enabling them to make better choices in their lives.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

After Donald Trump was first elected, the same political scientists who had adamantly insisted that he could never win a presidential election quickly coalesced on the same interpretation of his success. He was an authoritarian populist who cleaved the electorate into “real” Americans and everybody else, promising to put the former in charge while banishing the latter to the margins (or, according to the more extreme alarmists, putting them in camps). On this interpretation, two things were intrinsically linked: Trump’s demagogic talent for mobilizing popular opinion against the norms and values of a deeply mistrusted establishment; and his apparent alliance with a predominantly white and elderly electorate that had experienced a decline in their social status, feared the future, and was ready to resist change by any means necessary.

After Donald Trump was first elected, the same political scientists who had adamantly insisted that he could never win a presidential election quickly coalesced on the same interpretation of his success. He was an authoritarian populist who cleaved the electorate into “real” Americans and everybody else, promising to put the former in charge while banishing the latter to the margins (or, according to the more extreme alarmists, putting them in camps). On this interpretation, two things were intrinsically linked: Trump’s demagogic talent for mobilizing popular opinion against the norms and values of a deeply mistrusted establishment; and his apparent alliance with a predominantly white and elderly electorate that had experienced a decline in their social status, feared the future, and was ready to resist change by any means necessary. Unknowability was everywhere, not just in my interactions with people, but in the life and world I was eagerly observing. One morning early, maybe five a.m., I woke in a one-room shack of boards with a dirt floor and a thatched roof. It was raining. I had no bed; slept on a pallet. The thatch leaked, making the floor a muddy lake whose shore brushed my pallet.

Unknowability was everywhere, not just in my interactions with people, but in the life and world I was eagerly observing. One morning early, maybe five a.m., I woke in a one-room shack of boards with a dirt floor and a thatched roof. It was raining. I had no bed; slept on a pallet. The thatch leaked, making the floor a muddy lake whose shore brushed my pallet.

C

C In 2021, writer Will Hall began scraping Kevin Killian’s reviews from Amazon’s servers and, thanks largely to his efforts, Semiotext(e) published Kevin Killian: Selected Amazon Reviews in November. The 697-page collection rescues from obscurity some of the over two thousand reviews the poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, editor, critic, and artist posted to the platform from 2003 until his death in 2019. He was a great consumer of books, music, and film but also discussed the odd product. Killian’s reviews can be read as meditations on the objects and media that populated our lives for the first twenty-five years of the twenty-first century. He imbued ordinary items – duct tape, a toaster, a DVD—with personal meaning.

In 2021, writer Will Hall began scraping Kevin Killian’s reviews from Amazon’s servers and, thanks largely to his efforts, Semiotext(e) published Kevin Killian: Selected Amazon Reviews in November. The 697-page collection rescues from obscurity some of the over two thousand reviews the poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, editor, critic, and artist posted to the platform from 2003 until his death in 2019. He was a great consumer of books, music, and film but also discussed the odd product. Killian’s reviews can be read as meditations on the objects and media that populated our lives for the first twenty-five years of the twenty-first century. He imbued ordinary items – duct tape, a toaster, a DVD—with personal meaning. I’ve come to see this as a basic dynamic in math education reform: an illusory spirit of consensus. Clearly math education needs more something. But more what?

I’ve come to see this as a basic dynamic in math education reform: an illusory spirit of consensus. Clearly math education needs more something. But more what? I

I  T

T I

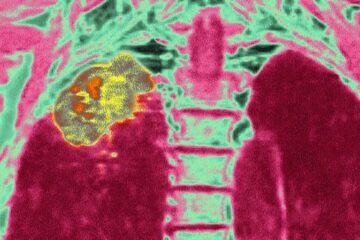

I Scientists have disguised tumours to ‘look’ similar to

Scientists have disguised tumours to ‘look’ similar to  Twin Peaks first aired in 1991. A tragic and often frightening mystery, it centred on the violent murder of a beautiful teenage girl in a strange, small town nestled in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. The protagonist was a handsome FBI agent who drank black coffee and spoke in riddles. There was a lot of

Twin Peaks first aired in 1991. A tragic and often frightening mystery, it centred on the violent murder of a beautiful teenage girl in a strange, small town nestled in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. The protagonist was a handsome FBI agent who drank black coffee and spoke in riddles. There was a lot of

In December, 37 colleagues and I published a

In December, 37 colleagues and I published a