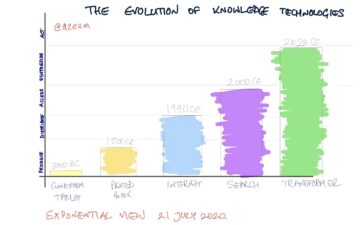

Azeem Azhar at Exponential View:

OpenAI released yet another add-on on to its growing suite of AI tools: DeepResearch. The product, which shares its name with Google Gemini’s Deep Research tool, also does near the exact same thing. For a given research question it will formulate a research plan and consult a variety of sources to provide a compelling research brief.

OpenAI released yet another add-on on to its growing suite of AI tools: DeepResearch. The product, which shares its name with Google Gemini’s Deep Research tool, also does near the exact same thing. For a given research question it will formulate a research plan and consult a variety of sources to provide a compelling research brief.

DeepResearch is a milestone in how we access and manipulate knowledge. When GPT-3 was first made available a few years ago, it quickly became clear that these LLM-based tools would create a new paradigm for accessing information. In A Short History of Knowledge Technologies, I argued:

[GPT-3] does something the search engine doesn’t do, but which we want it to do. It is capable of synthesising the information and presenting it in a near usable form.

Four years is an eternity in AI, of course. GPT-4 is much more powerful than GPT-3 and the new family of reasoning models, o1 and o3, are in a class of their own. DeepResearch from OpenAI goes much further than my short quote suggested.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism.

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism. Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says.

Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says. Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after.

Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after. When the French crime film

When the French crime film L

L F

F A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents.

A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents. Reading a Rachel Cusk novel is like watching a recording of your everyday life, with all your subtly unflattering habits, traits, and actions. A conversation with your seatmate on a plane reveals that you manipulate your family like items on an Excel sheet. A lunch meeting about a potential business partnership discloses that people only matter to you if you profit from them. No one at your get-together of acquaintances reacts when a woman admits she abuses her dog.

Reading a Rachel Cusk novel is like watching a recording of your everyday life, with all your subtly unflattering habits, traits, and actions. A conversation with your seatmate on a plane reveals that you manipulate your family like items on an Excel sheet. A lunch meeting about a potential business partnership discloses that people only matter to you if you profit from them. No one at your get-together of acquaintances reacts when a woman admits she abuses her dog. Left-wing activists benefit from a framework where “center left” just means “whatever the left says, but less,” because this gives them the power to alter what it means to be on the center left just by advocating for more extreme views. If the left gets more extreme, the center left must follow them at least part of the way, or risk being labeled as “on the right.” That can be an effective rhetorical cudgel against those who care about being “on the left.” And it raises the question: If your position is that you support what we do (just less), why not go all the way? Not only does this framework provide too much power to activists, it also harms the electoral prospects of center-left political parties, like the Democrats. If the best account the Democrats can give of their stance on cultural issues is “Whatever activists say, but less,” they’re setting themselves up for defeat. That message alienates everyone.

Left-wing activists benefit from a framework where “center left” just means “whatever the left says, but less,” because this gives them the power to alter what it means to be on the center left just by advocating for more extreme views. If the left gets more extreme, the center left must follow them at least part of the way, or risk being labeled as “on the right.” That can be an effective rhetorical cudgel against those who care about being “on the left.” And it raises the question: If your position is that you support what we do (just less), why not go all the way? Not only does this framework provide too much power to activists, it also harms the electoral prospects of center-left political parties, like the Democrats. If the best account the Democrats can give of their stance on cultural issues is “Whatever activists say, but less,” they’re setting themselves up for defeat. That message alienates everyone. Why Austrian literature? Sebald was not Austrian, though his south German birthplace, Wertach, was within walking distance of the Austrian border. Austrian literature appealed to his feeling for marginality. Its major writers, from Franz Grillparzer via Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Kafka to Peter Handke, do not fit easily into the pattern of German literature, stretching from Goethe via Thomas Mann to Günter Grass. They excel, in Sebald’s view, in exploring psychological states ranging from obsession and melancholia to schizophrenic breakdown. One notably empathetic essay concerns an actual schizophrenic, Ernst Herbeck (1920–91), who was confined for fifty years in a mental hospital near Klosterneuburg, north of Vienna, where Sebald visited him. Herbeck wrote a large number of poems with enigmatic lines, such as ‘the raven leads the pious on’. Although these poems yield nothing to academic exegesis, they not only linger in the memory but may also, Sebald suggests, reveal the primitive processes through which poetic language arises.

Why Austrian literature? Sebald was not Austrian, though his south German birthplace, Wertach, was within walking distance of the Austrian border. Austrian literature appealed to his feeling for marginality. Its major writers, from Franz Grillparzer via Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Kafka to Peter Handke, do not fit easily into the pattern of German literature, stretching from Goethe via Thomas Mann to Günter Grass. They excel, in Sebald’s view, in exploring psychological states ranging from obsession and melancholia to schizophrenic breakdown. One notably empathetic essay concerns an actual schizophrenic, Ernst Herbeck (1920–91), who was confined for fifty years in a mental hospital near Klosterneuburg, north of Vienna, where Sebald visited him. Herbeck wrote a large number of poems with enigmatic lines, such as ‘the raven leads the pious on’. Although these poems yield nothing to academic exegesis, they not only linger in the memory but may also, Sebald suggests, reveal the primitive processes through which poetic language arises. Every day, billions of cells in our body divide or die off. It’s all part of the intricate processes that keep blood flowing from our heart, food moving through our gut and our skin regenerating. Once in a while, though, something goes awry, and cells that should stop growing or die simply don’t. Left unchecked, those cells can turn into cancer.

Every day, billions of cells in our body divide or die off. It’s all part of the intricate processes that keep blood flowing from our heart, food moving through our gut and our skin regenerating. Once in a while, though, something goes awry, and cells that should stop growing or die simply don’t. Left unchecked, those cells can turn into cancer. Born out of necessity, America’s Black labor movements have left an indelible mark upon the social fabric of our country. For hundreds of years Black activists have poured blood, sweat, and tears into organizing the American labor force for better working conditions. Until relatively recently, Black Americans were excluded from major unions, and therefore had to create separate institutions that fought for Black workers. Black men organized against all odds in the agriculture sector, and Black women, who were often excluded from leadership and sometimes even membership in other Black organizations, were early proponents of labor reform by unionizing domestic workers. As civil rights in America progressed, major unions integrated and partnered with Black labor movements across America to champion both economic reform and racial justice. Today, union membership in the Black community is declining despite the long tradition of Black-led labor activism.

Born out of necessity, America’s Black labor movements have left an indelible mark upon the social fabric of our country. For hundreds of years Black activists have poured blood, sweat, and tears into organizing the American labor force for better working conditions. Until relatively recently, Black Americans were excluded from major unions, and therefore had to create separate institutions that fought for Black workers. Black men organized against all odds in the agriculture sector, and Black women, who were often excluded from leadership and sometimes even membership in other Black organizations, were early proponents of labor reform by unionizing domestic workers. As civil rights in America progressed, major unions integrated and partnered with Black labor movements across America to champion both economic reform and racial justice. Today, union membership in the Black community is declining despite the long tradition of Black-led labor activism. Before the election,

Before the election,