Chantel Tattoli in The Paris Review:

“Zora!” Alice Walker howled in the cemetery. “I hope you don’t think I’m going to stand out here all day, with these snakes watching me and these ants having a field day.” It was August 1973. Zora Neale Hurston, who was then thirteen years dead, was a mudslinging protofeminist novelist-folklorist-playwright-ethnographer, not to be crossed, and she had climbed to minor literary stardom in the thirties with her accounts of the Southern African American experience, specifically black Southern womanhood. She was, in the words of her friend Langston Hughes, “the most amusing” among New York’s “Niggerati.” She hailed herself as their queen. But Hurston was complicated. “Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves,” she once wrote. “It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you.” She declined to recall a single memory of racial prejudice in her autobiography. Her sycophantic attitude toward her white patrons, Red-baiting, and eventual criticism of Brown v. Board of Education had rotted her name. “She was quite capable of saying, writing, or doing things different from what one might have wished,” Walker admitted. But she forgave Hurston. As Hurston herself declared, “How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?”

“Zora!” Alice Walker howled in the cemetery. “I hope you don’t think I’m going to stand out here all day, with these snakes watching me and these ants having a field day.” It was August 1973. Zora Neale Hurston, who was then thirteen years dead, was a mudslinging protofeminist novelist-folklorist-playwright-ethnographer, not to be crossed, and she had climbed to minor literary stardom in the thirties with her accounts of the Southern African American experience, specifically black Southern womanhood. She was, in the words of her friend Langston Hughes, “the most amusing” among New York’s “Niggerati.” She hailed herself as their queen. But Hurston was complicated. “Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves,” she once wrote. “It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you.” She declined to recall a single memory of racial prejudice in her autobiography. Her sycophantic attitude toward her white patrons, Red-baiting, and eventual criticism of Brown v. Board of Education had rotted her name. “She was quite capable of saying, writing, or doing things different from what one might have wished,” Walker admitted. But she forgave Hurston. As Hurston herself declared, “How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?”

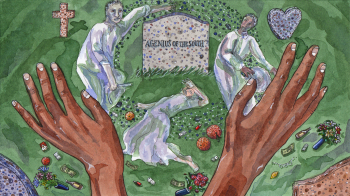

And so: nearly a decade before Walker published The Color Purple, a sister masterpiece to Their Eyes Were Watching God, the contributing editor at Ms. magazine stood in weeds up to her waist in Florida while sand and bugs poured into her shoes, looking for Hurston. Walker had flown from Jackson, Mississippi, to Orlando and driven to nearby Eatonville, the prideful all-black town where Hurston was raised, but not, as Walker learned from an octogenarian former classmate—Mathilda Moseley, teller of “woman-is-smarter-than-man” tales in Hurston’s Mules and Men—where she was put under.

Walker’s quest took her to Fort Pierce, on the Atlantic Coast, to the dead end of Seventeenth Street, to the Garden of Heavenly Rest. "In fact, I’m going to call you just one or two more times,” Walker swore. Hurston was somewhere in the crummy segregated burial ground; trouble was, her grave was unmarked. “Zo-ra!” Walker roared. And, as if Hurston had shoved her, Walker stumbled into a sunken rectangle in the heart of the yard: presumably Zora.

More here.

Rachel Z. Arndt at The Believer: