Joseph Schreiber at The Quarterly Conversation:

The Danish transgender performance artist, has, over the course of her career, presented, masqueraded, invented, and re-invented herself many times, even having her birth-identified self, Claus Beck-Nielsen, declared dead along the way. (He was ultimately revived when the lack of any identity altogether proved too difficult to sustain.) The multi-faceted Madame Nielsen is a novelist, poet, artist, performer, stage director, composer, and singer. With The Endless Summer, newly released from Open Letter Books in a translation by Gaye Kynoch, Nielsen weaves a tale that sidesteps the common expectations of narrative progress and character development. Rather, an odd cast of characters is choreographed through a shifting, dreamlike landscape openly reminiscent of David Lynch, complete with digressions into side stories, tales from the past, and glances into the future. The stories are continually being started, interrupted, and resumed again. The influence of Proust and other French novelists is evident, but Nielsen’s wistful narrator, who will ultimately become an actor, demonstrates a strong theatrical sensibility throughout.

The novel opens with a simple statement, the oddly incomplete sentence: “The young boy, who is perhaps a girl, but does not know it yet.” This phrase will be echoed, with slightly different shades, gradation, and detail, throughout the text. Likewise, the other main characters’ defining characteristics or curious features will be continually evoked, elaborated, and elegized as the tale unwinds.

more here.

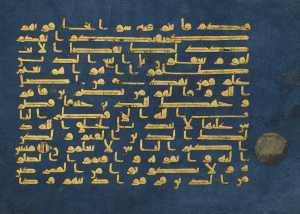

What is shariʿa? It is often translated as “Islamic law,” as if it represented the law in its entirety. It is also commonly thought to be a rigid set of practices and punishments inherited directly from early Islam that are meant to be applied in a single inflexible manner. But none of this is accurate.

What is shariʿa? It is often translated as “Islamic law,” as if it represented the law in its entirety. It is also commonly thought to be a rigid set of practices and punishments inherited directly from early Islam that are meant to be applied in a single inflexible manner. But none of this is accurate.