Jared Diamond in the New York Times:

For over a decade, National Geographic’s Genographic Project has been collecting saliva samples from willing participants, analyzing small pieces of their mother’s and father’s DNA (so-called mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome DNA, respectively). In return, there is fascinating personal information to be had — about individual ancestries, and about close relatives whose existence had been previously unknown.

But geneticists can now achieve far more than those limited analyses could, and can approach their dream of using genetic evidence to reconstruct past human migrations. One reason is that methods for extracting DNA from bones of ancient humans who lived tens of thousands of years ago have improved. It’s possible now to separate their DNA from all the bacterial and modern human DNA that contaminates those bones. Another reason is that, due especially to the Harvard geneticist David Reich and his colleagues, we now have efficient methods for analyzing whole ancient human genomes, not just the few percent contributed by mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome.

In “Who We Are and How We Got Here,” Reich summarizes this rapidly advancing field. He begins with a crash course on genetics and DNA sequencing, then discusses the Neanderthals and “ghost populations” whose existences are inferred from genetic evidence although they no longer exist. Most of the book then consists of chapters reconstructing the histories of modern Europeans, Indians, Native Americans, East Asians and Africans. Concluding chapters probe the controversial subject of race and identity, and prospects for new discoveries. I’ll illustrate Reich’s chapters with three examples: Neanderthals, Europeans and Polynesians.

More here.

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true.

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true. Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!”

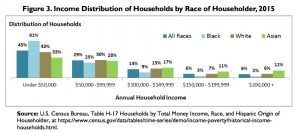

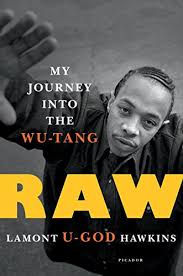

Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!” Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”

Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”