Dalton Conley in the New York Times:

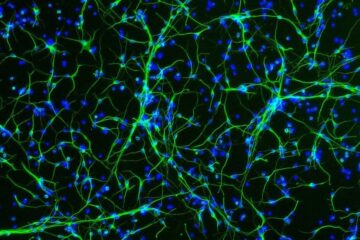

Since Sir Francis Galton coined the phrase “nature versus nurture” 150 years ago, the debate about what makes us who we are has dominated the human sciences.

Since Sir Francis Galton coined the phrase “nature versus nurture” 150 years ago, the debate about what makes us who we are has dominated the human sciences.

Do genes determine our destiny, as the hereditarians would say? Or do we enter the world as blank slates, formed only by what we encounter in our homes and beyond? What started as an intellectual debate quickly expanded to whatever anyone wanted it to mean, invoked in arguments about everything from free will to race to inequality to whether public policy can, or should, level the playing field.

Today, however, a new realm of science is poised to upend the debate — not by declaring victory for one side or the other, nor even by calling a tie, but rather by revealing they were never in opposition in the first place. Through this new vantage, nature and nurture are not even entirely distinguishable, because genes and environment don’t operate in isolation; they influence each other and to a very real degree even create each other.

The new field is called sociogenomics, a fusion of behavioral science and genetics that I have been closely involved with for over a decade. Though the field is still in its infancy, its philosophical implications are staggering.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

If critique could kill, neoliberalism would long be dead. So far, however, neither decades of intellectual opposition from the left and right nor the past decade of populist politics has done more than erode some measure of neoliberalism’s ideological preeminence. Talk from the right of “pro-family” policies, such as tax breaks and subsidies for having children, or moves by the Biden administration to secure domestic manufacturing of critical high-technology goods may hearten neoliberalism’s foes (even as they further blur the ideological map of American politics). Neither, however, offers anything like a consensus to replace the vision that, since the crises of the 1970s, has, with whatever degree of discontent, guided our collective thought and action.

If critique could kill, neoliberalism would long be dead. So far, however, neither decades of intellectual opposition from the left and right nor the past decade of populist politics has done more than erode some measure of neoliberalism’s ideological preeminence. Talk from the right of “pro-family” policies, such as tax breaks and subsidies for having children, or moves by the Biden administration to secure domestic manufacturing of critical high-technology goods may hearten neoliberalism’s foes (even as they further blur the ideological map of American politics). Neither, however, offers anything like a consensus to replace the vision that, since the crises of the 1970s, has, with whatever degree of discontent, guided our collective thought and action. An Australian man in his forties has become the first person in the world to leave hospital with an artificial heart made of titanium. The device is used as a stopgap for people with heart failure who are waiting for a donor heart, and previous recipients of this type of artificial heart had remained in US hospitals while it was in place.

An Australian man in his forties has become the first person in the world to leave hospital with an artificial heart made of titanium. The device is used as a stopgap for people with heart failure who are waiting for a donor heart, and previous recipients of this type of artificial heart had remained in US hospitals while it was in place. [SSW: The next quote is Pinker’s rebuttal of a common response to Judith Rich Harris’s claim that parents have little impact on their kids.] “‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my children?’ What a question! Yes, of course it matters… First, parents wield enormous power over their children, and their actions can make a big difference to their happiness… It is not OK for parents to beat, humiliate, deprive, or neglect their children, because those are awful things for a big strong person to do to a small helpless one… Second, a parent and a child have a human relationship. No one ever asks, ‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my husband or wife?’ even though no one but a newlywed believes that one can change the personality of one’s spouse. Husbands and wives are nice to each other (or should be) not to pound the other’s personality into a desired shape but to build a deep and satisfying relationship.”

[SSW: The next quote is Pinker’s rebuttal of a common response to Judith Rich Harris’s claim that parents have little impact on their kids.] “‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my children?’ What a question! Yes, of course it matters… First, parents wield enormous power over their children, and their actions can make a big difference to their happiness… It is not OK for parents to beat, humiliate, deprive, or neglect their children, because those are awful things for a big strong person to do to a small helpless one… Second, a parent and a child have a human relationship. No one ever asks, ‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my husband or wife?’ even though no one but a newlywed believes that one can change the personality of one’s spouse. Husbands and wives are nice to each other (or should be) not to pound the other’s personality into a desired shape but to build a deep and satisfying relationship.” The French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace crisply articulated his expectation that the universe was fully knowable in 1814, asserting that a sufficiently clever “demon” could predict the entire future given a complete knowledge of the present. His thought experiment marked the height of optimism about what physicists might forecast. Since then, reality has repeatedly humbled their ambitions to understand it.

The French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace crisply articulated his expectation that the universe was fully knowable in 1814, asserting that a sufficiently clever “demon” could predict the entire future given a complete knowledge of the present. His thought experiment marked the height of optimism about what physicists might forecast. Since then, reality has repeatedly humbled their ambitions to understand it. We can give ourselves far, far more than Donald Trump can ever take away, but it will—it will take extraordinary efforts. It won’t be business as usual. We will have to do things we haven’t imagined before, at speeds we didn’t think possible. […] I know, I know that these are dark days, dark days brought on by a country we can no longer trust. We are getting over the shock, but let us never forget the lessons: we have to look after ourselves and we have to look out for each other. We need to pull together in the tough days ahead.

We can give ourselves far, far more than Donald Trump can ever take away, but it will—it will take extraordinary efforts. It won’t be business as usual. We will have to do things we haven’t imagined before, at speeds we didn’t think possible. […] I know, I know that these are dark days, dark days brought on by a country we can no longer trust. We are getting over the shock, but let us never forget the lessons: we have to look after ourselves and we have to look out for each other. We need to pull together in the tough days ahead. T

T What do a mobile shooting game, a nuclear power plant, and a local Chinese government office have in common? In the past two months, they have all tried incorporating DeepSeek’s R1

What do a mobile shooting game, a nuclear power plant, and a local Chinese government office have in common? In the past two months, they have all tried incorporating DeepSeek’s R1  Given the chance to become a movie director in Hollywood or a professor of philosophy at Harvard, I imagine very few of us would choose the academic life. The money and fame of being a movie director are far more tantalizing than teaching Plato, Kant, or Simone de Beauvoir. Terrence Malick chose to become a movie director instead of a philosophy professor, but not for the reasons you might think. It was not money and fame that convinced him, but the inability of philosophy courses to help “him understand himself and his place in the order of the cosmos” as Martin Woessner explained in a

Given the chance to become a movie director in Hollywood or a professor of philosophy at Harvard, I imagine very few of us would choose the academic life. The money and fame of being a movie director are far more tantalizing than teaching Plato, Kant, or Simone de Beauvoir. Terrence Malick chose to become a movie director instead of a philosophy professor, but not for the reasons you might think. It was not money and fame that convinced him, but the inability of philosophy courses to help “him understand himself and his place in the order of the cosmos” as Martin Woessner explained in a  Relying on an experienced team of scientists and $200 million in initial funding, Lila has been developing an A.I. program trained on published and experimental data, as well as the scientific process and reasoning. The start-up then lets that A.I. software run experiments in automated, physical labs with a few scientists to assist.

Relying on an experienced team of scientists and $200 million in initial funding, Lila has been developing an A.I. program trained on published and experimental data, as well as the scientific process and reasoning. The start-up then lets that A.I. software run experiments in automated, physical labs with a few scientists to assist. The early days of the second Trump Administration have been greeted with both shock and a search for lessons from history. Journalists have turned to the Nixon Administration’s attempts to “impound” congressionally allocated funds as both a precedent for Trump’s actions and evidence of their illegality. The rollback of DEI and the targeted firings of women and Black leaders across the military and the civil service is redolent of the southern “Redemption” that brought Jim Crow to power in the 1870s and 1880s after the end of Reconstruction. Notably absent in many of these discussions is the last time mass firings and large-scale workplace intimidation occurred in the federal government: the McCarthy Era and the Second Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

The early days of the second Trump Administration have been greeted with both shock and a search for lessons from history. Journalists have turned to the Nixon Administration’s attempts to “impound” congressionally allocated funds as both a precedent for Trump’s actions and evidence of their illegality. The rollback of DEI and the targeted firings of women and Black leaders across the military and the civil service is redolent of the southern “Redemption” that brought Jim Crow to power in the 1870s and 1880s after the end of Reconstruction. Notably absent in many of these discussions is the last time mass firings and large-scale workplace intimidation occurred in the federal government: the McCarthy Era and the Second Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Talk about truth in advertising: MAYHEM is its own charm offensive, a massive attack of good vibes. It is a project designed to remind listeners why they fell in love with her in the first place, before the jazz belting or the traditional singer-songwriter gravitas or movie stardom. Inspiration from fiancé Michael Polansky, entrepreneur and one of the album’s executive producers, to return to her pop roots prompted an internal survey—Gaga told EW that instead of seeking to reinvent her sound, “I started to think about what makes me me? What are my references? What are my inspirations?” MAYHEM, then, isn’t the sound of someone reheating her nachos on the sly and trying to pass them off as fresh—it’s a full-on cooking show devoted to the art of nacho-reheating.

Talk about truth in advertising: MAYHEM is its own charm offensive, a massive attack of good vibes. It is a project designed to remind listeners why they fell in love with her in the first place, before the jazz belting or the traditional singer-songwriter gravitas or movie stardom. Inspiration from fiancé Michael Polansky, entrepreneur and one of the album’s executive producers, to return to her pop roots prompted an internal survey—Gaga told EW that instead of seeking to reinvent her sound, “I started to think about what makes me me? What are my references? What are my inspirations?” MAYHEM, then, isn’t the sound of someone reheating her nachos on the sly and trying to pass them off as fresh—it’s a full-on cooking show devoted to the art of nacho-reheating. Ping-pong is not a game that lends itself well to chatter. It demands sharp focus, quick reflexes, and a light touch, and the dozen players who have gathered this Monday afternoon at PingPod, a table-tennis venue on West 99th Street, are locked in the wordless rhythms of the back-and-forth. Aside from the occasional “Nice spin!” or grunt of self-reproach, the room is filled with the hollow percussion of little white balls glancing off paddles, skipping over the tops of the black tables, and rattling across the floor.

Ping-pong is not a game that lends itself well to chatter. It demands sharp focus, quick reflexes, and a light touch, and the dozen players who have gathered this Monday afternoon at PingPod, a table-tennis venue on West 99th Street, are locked in the wordless rhythms of the back-and-forth. Aside from the occasional “Nice spin!” or grunt of self-reproach, the room is filled with the hollow percussion of little white balls glancing off paddles, skipping over the tops of the black tables, and rattling across the floor. Women’s brains are superior to men’s in at least in one respect — they age more slowly. And now, a group of researchers reports that they have found a gene in mice that rejuvenates female brains. Humans have the same gene. The discovery suggests a possible way to help both women and men avoid cognitive declines in advanced age. The

Women’s brains are superior to men’s in at least in one respect — they age more slowly. And now, a group of researchers reports that they have found a gene in mice that rejuvenates female brains. Humans have the same gene. The discovery suggests a possible way to help both women and men avoid cognitive declines in advanced age. The