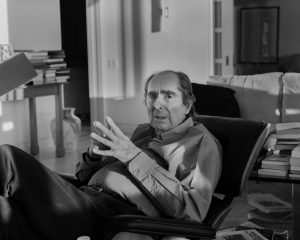

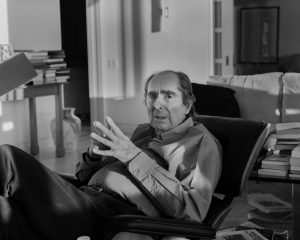

Zadie Smith in The New Yorker:

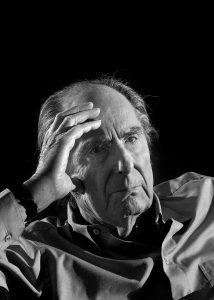

One time, I was having a conversation with Philip Roth about lane swimming, a thing it turned out we both liked to do, although he could swim much farther and much faster. He asked me, “What do you think about as you do each length?” I told him the dull truth. “I think, first length, first length, first length, and then second length, second length, second length. And so on.” That made him laugh. “You wanna know what I think about?” I did. “I choose a year. Say, 1953. Then I think about what happened in my life or within my little circle in that year. Then I move on to thinking about what happened in Newark, or New York. Then in America. And then if I’m going the distance I might start thinking about Europe, too. And so on.” That made me laugh. The energy, the reach, the precision, the breadth, the curiosity, the will, the intelligence. Roth in the swimming pool was no different than Roth at his standing desk. He was a writer all the way down. It was not diluted with other things as it is—mercifully!—for the rest of us. He was writing taken neat, and everything he did was at the service of writing. At an unusually tender age, he learned not to write to make people think well of him, nor to display to others, through fiction, the right sort of ideas, so they could think him the right sort of person. “Literature isn’t a moral beauty contest,” he once said. For Roth, literature was not a tool of any description. It was the venerated thing in itself. He loved fiction and (unlike so many half or three-quarter writers) was never ashamed of it. He loved it in its irresponsibility, in its comedy, in its vulgarity, and its divine independence. He never confused it with other things made of words, like statements of social justice or personal rectitude, journalism or political speeches, all of which are vital and necessary for lives we live outside of fiction, but none of which are fiction, which is a medium that must always allow itself, as those other forms often can’t, the possibility of expressing intimate and inconvenient truths.

One time, I was having a conversation with Philip Roth about lane swimming, a thing it turned out we both liked to do, although he could swim much farther and much faster. He asked me, “What do you think about as you do each length?” I told him the dull truth. “I think, first length, first length, first length, and then second length, second length, second length. And so on.” That made him laugh. “You wanna know what I think about?” I did. “I choose a year. Say, 1953. Then I think about what happened in my life or within my little circle in that year. Then I move on to thinking about what happened in Newark, or New York. Then in America. And then if I’m going the distance I might start thinking about Europe, too. And so on.” That made me laugh. The energy, the reach, the precision, the breadth, the curiosity, the will, the intelligence. Roth in the swimming pool was no different than Roth at his standing desk. He was a writer all the way down. It was not diluted with other things as it is—mercifully!—for the rest of us. He was writing taken neat, and everything he did was at the service of writing. At an unusually tender age, he learned not to write to make people think well of him, nor to display to others, through fiction, the right sort of ideas, so they could think him the right sort of person. “Literature isn’t a moral beauty contest,” he once said. For Roth, literature was not a tool of any description. It was the venerated thing in itself. He loved fiction and (unlike so many half or three-quarter writers) was never ashamed of it. He loved it in its irresponsibility, in its comedy, in its vulgarity, and its divine independence. He never confused it with other things made of words, like statements of social justice or personal rectitude, journalism or political speeches, all of which are vital and necessary for lives we live outside of fiction, but none of which are fiction, which is a medium that must always allow itself, as those other forms often can’t, the possibility of expressing intimate and inconvenient truths.

Roth always told the truth—his own, subjective truth—through language and through lies, the twin engines at the embarrassing heart of literature. Embarrassing to others, never to Roth. Second selves, fake selves, fantasy selves, replacement selves, horrifying selves, hilarious, mortifying selves—he welcomed them all. Like all writers, there were things and ideas that lay beyond his ken or conception; he had blind spots, prejudices, selves he could imagine only partially, or selves he mistook or mislaid. But, unlike many writers, he did not aspire to perfect vision. He knew that to be an impossibility. Subjectivity is limited by the vision of the subject, and the task of writing is to do the best with what you have. Roth used every little scrap of what he had. Nothing was held back or protected from writing, nothing saved for a rainy day. He wrote every single book he intended to write and said every last thing he meant to say. For a writer, there is no greater aspiration than that. To swim all eighty-five lengths of the pool and then get out without looking back.

More here.

By the time he came to write Finnegans Wake, Joyce had moved beyond trying to imitate musical forms, and described his novel not as a “blending of literature and music”, but rather as “pure music”. Writing to his daughter Lucia, Joyce explained, “Lord knows what my prose means. In a word, it is pleasing to the ear . . . . That is enough, it seems to me”, and in conversation, he declared, “judging from modern trends it seems that all the arts are tending towards the abstraction of music; and what I am writing at present is entirely governed by that purpose”. This offers perhaps the best way to approach his most complex work. Joyce emphasizes how, “if anyone doesn’t understand a passage, all he need do is read it aloud”, and such an approach certainly helps here: “and the rhymers’ world was with reason the richer for a wouldbe ballad, to the balledder of which the world of cumannity singing owes a tribute for having placed on the planet’s melomap his lay of the vilest bogeyer but most attractionable avatar the world has ever had to explain for”.

By the time he came to write Finnegans Wake, Joyce had moved beyond trying to imitate musical forms, and described his novel not as a “blending of literature and music”, but rather as “pure music”. Writing to his daughter Lucia, Joyce explained, “Lord knows what my prose means. In a word, it is pleasing to the ear . . . . That is enough, it seems to me”, and in conversation, he declared, “judging from modern trends it seems that all the arts are tending towards the abstraction of music; and what I am writing at present is entirely governed by that purpose”. This offers perhaps the best way to approach his most complex work. Joyce emphasizes how, “if anyone doesn’t understand a passage, all he need do is read it aloud”, and such an approach certainly helps here: “and the rhymers’ world was with reason the richer for a wouldbe ballad, to the balledder of which the world of cumannity singing owes a tribute for having placed on the planet’s melomap his lay of the vilest bogeyer but most attractionable avatar the world has ever had to explain for”.

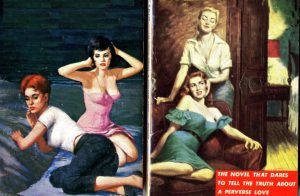

Another early lesbian-pulp and layered reading experience is Spring Fire (1952), by Vin Packer (one of the pseudonyms of the prolific author Marijane Meaker). Although its seemingly naive Americana tone reads today as camp, the novel plays with semantics and morality in its own way. Within this supposed “steamy page-turner … once told in whispers” is the tale of a newbie Midwestern student named Susan Mitchell. (She goes by—you guessed it—Mitch.) Mitch is seduced by her sorority sister, the come-hither green-eyed Leda, when she asks Mitch to give her a back rub and then suddenly “rolled over and lay with her breasts pushed up toward Mitch’s hands.” Although the prose at first rings as high-strung, it echoes with complex undertones. “There are a lot of people who love both [men and women] and no one gives a damn, and they just say you’re oversexed,” Leda explains to Mitch. “But they start getting interested when you stick to one sex. Like you’ve been doing, Mitch. I couldn’t love you if you were a Lesbian.” (Note the capital l.)

Another early lesbian-pulp and layered reading experience is Spring Fire (1952), by Vin Packer (one of the pseudonyms of the prolific author Marijane Meaker). Although its seemingly naive Americana tone reads today as camp, the novel plays with semantics and morality in its own way. Within this supposed “steamy page-turner … once told in whispers” is the tale of a newbie Midwestern student named Susan Mitchell. (She goes by—you guessed it—Mitch.) Mitch is seduced by her sorority sister, the come-hither green-eyed Leda, when she asks Mitch to give her a back rub and then suddenly “rolled over and lay with her breasts pushed up toward Mitch’s hands.” Although the prose at first rings as high-strung, it echoes with complex undertones. “There are a lot of people who love both [men and women] and no one gives a damn, and they just say you’re oversexed,” Leda explains to Mitch. “But they start getting interested when you stick to one sex. Like you’ve been doing, Mitch. I couldn’t love you if you were a Lesbian.” (Note the capital l.) Denis’s films are filled with lush scenes of the natural world—African deserts, snowy Alpine fields, and the mineral-green waters of the South Pacific—and characters who tend to reveal themselves not through dialogue but through how they move and look. Alex Descas, one of the actors with whom Denis has worked longest, and who credits her with writing complicated, realistic roles for black actors at a time when few others did, described her artistic mode succinctly: “Film is not theatre,” he told me. Last month, at a screening of her latest movie, “Let the Sunshine In,” at the IFC Center, in Manhattan, Denis said, “I once read that I like to film bodies. No! But, if you choose someone, that person hasa body. They have feet, hands, hair, breasts, ass—all of that is part of what is important.” The film stars Juliette Binoche, as a divorced painter who dates men she shouldn’t: a married banker, a narcissistic actor, a standoffish curator. “She wanted my character to be beautiful and desirable and luminous,” Binoche told me. In the final shot, the camera—which one critic described as “smitten”—stays on her smiling face, which is ablaze with delusion and hope. Denis, according to Binoche, “works like a portrait painter.”

Denis’s films are filled with lush scenes of the natural world—African deserts, snowy Alpine fields, and the mineral-green waters of the South Pacific—and characters who tend to reveal themselves not through dialogue but through how they move and look. Alex Descas, one of the actors with whom Denis has worked longest, and who credits her with writing complicated, realistic roles for black actors at a time when few others did, described her artistic mode succinctly: “Film is not theatre,” he told me. Last month, at a screening of her latest movie, “Let the Sunshine In,” at the IFC Center, in Manhattan, Denis said, “I once read that I like to film bodies. No! But, if you choose someone, that person hasa body. They have feet, hands, hair, breasts, ass—all of that is part of what is important.” The film stars Juliette Binoche, as a divorced painter who dates men she shouldn’t: a married banker, a narcissistic actor, a standoffish curator. “She wanted my character to be beautiful and desirable and luminous,” Binoche told me. In the final shot, the camera—which one critic described as “smitten”—stays on her smiling face, which is ablaze with delusion and hope. Denis, according to Binoche, “works like a portrait painter.” One evening in March, a pale-blue layer of light began spreading across the plaza outside the United Nations headquarters in New York. Emanating from banks of leds, it appeared to undulate like the surface of the sea high above the heads of passing pedestrians. The effect may have been ethereal but the warning was all too real: the light submerged the plaza to the same depth that water may do if nothing is done to control rising sea levels. Called “Waterlicht” (Waterlight), the installation was the work of Daan Roosegaarde, a Dutch artist; New York was just one stop on a tour of global cities. Roosegaarde’s intention is to focus people’s minds on the prospect of a watery future. “Above all it gets people who might never do so talking about water and global warming,” he says. Often the conversation turns to keeping water out. But increasingly urban planners and designers are taking their cues from Rotterdam, the city where Roosegaarde lives and works: they are working out how to let water in. Like thousands of coastal cities from Shanghai to Miami, Osaka to New York, Rotterdam is under threat. More than 80% of this port on the Netherlands’ North Sea coast lies below sea level, the ocean kept at bay by a sophisticated system of levees, dykes, dams and storm-surge barriers known as the Delta Works. But by the end of the century those sea levels are predicted to rise by around a metre and the Netherlands is already seeing an increase in rainfall and flooding. To make matters worse, the thousands of pumps that remove groundwater up and down the country are causing the peat to dehydrate and the ground to sink. In recent years this has led to a shift in thinking: instead of working against the water, why not re-engineer the city to work with it?

One evening in March, a pale-blue layer of light began spreading across the plaza outside the United Nations headquarters in New York. Emanating from banks of leds, it appeared to undulate like the surface of the sea high above the heads of passing pedestrians. The effect may have been ethereal but the warning was all too real: the light submerged the plaza to the same depth that water may do if nothing is done to control rising sea levels. Called “Waterlicht” (Waterlight), the installation was the work of Daan Roosegaarde, a Dutch artist; New York was just one stop on a tour of global cities. Roosegaarde’s intention is to focus people’s minds on the prospect of a watery future. “Above all it gets people who might never do so talking about water and global warming,” he says. Often the conversation turns to keeping water out. But increasingly urban planners and designers are taking their cues from Rotterdam, the city where Roosegaarde lives and works: they are working out how to let water in. Like thousands of coastal cities from Shanghai to Miami, Osaka to New York, Rotterdam is under threat. More than 80% of this port on the Netherlands’ North Sea coast lies below sea level, the ocean kept at bay by a sophisticated system of levees, dykes, dams and storm-surge barriers known as the Delta Works. But by the end of the century those sea levels are predicted to rise by around a metre and the Netherlands is already seeing an increase in rainfall and flooding. To make matters worse, the thousands of pumps that remove groundwater up and down the country are causing the peat to dehydrate and the ground to sink. In recent years this has led to a shift in thinking: instead of working against the water, why not re-engineer the city to work with it? One time, I was having a conversation with

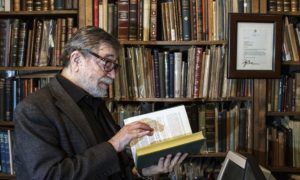

One time, I was having a conversation with  Artificial intelligence owes a lot of its smarts to Judea Pearl. In the 1980s he led efforts that allowed machines to reason probabilistically. Now he’s one of the field’s sharpest critics. In his latest book,

Artificial intelligence owes a lot of its smarts to Judea Pearl. In the 1980s he led efforts that allowed machines to reason probabilistically. Now he’s one of the field’s sharpest critics. In his latest book,  I leapt into the air, screaming at the top of my lungs with tears rolling down my cheeks as the news sank in. I had lost both of my parents when I was 16 years old, and I had often been sent home from school for unpaid tuition as I worked my way to a bachelor’s degree in my home country of Zimbabwe. But now, I was a Fulbright fellow. I was convinced that the award would propel my career to unconceivable heights. It was all the sweeter when I thought of my mother and how she used to cry over my report cards. At the time, I thought it was because I had not done well enough, but I later realized she was crying because she could not bear the idea that her poverty would keep me from reaching my full potential. I carried the burden of wanting to do her proud, and the fellowship was a huge step in that direction. It would also help me prove to the world that I was more than my family’s poverty. The numerous first-time opportunities the fellowship afforded—flying on a plane, staying in a hotel, moving to the United States—earned me respect in my small farming town. The chance to study and work abroad raised my own expectations sky-high as well.

I leapt into the air, screaming at the top of my lungs with tears rolling down my cheeks as the news sank in. I had lost both of my parents when I was 16 years old, and I had often been sent home from school for unpaid tuition as I worked my way to a bachelor’s degree in my home country of Zimbabwe. But now, I was a Fulbright fellow. I was convinced that the award would propel my career to unconceivable heights. It was all the sweeter when I thought of my mother and how she used to cry over my report cards. At the time, I thought it was because I had not done well enough, but I later realized she was crying because she could not bear the idea that her poverty would keep me from reaching my full potential. I carried the burden of wanting to do her proud, and the fellowship was a huge step in that direction. It would also help me prove to the world that I was more than my family’s poverty. The numerous first-time opportunities the fellowship afforded—flying on a plane, staying in a hotel, moving to the United States—earned me respect in my small farming town. The chance to study and work abroad raised my own expectations sky-high as well.

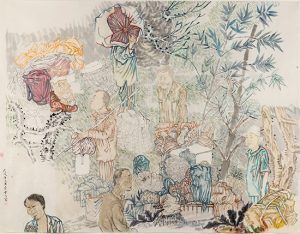

For Chinatown residents, Ji’s paintings may serve as an allegory of what is happening elsewhere; but for Chinese farmers and their families it is reality, one they are forced to confront as an everyday occurrence. In rural China today , extreme poverty has become a fact of life. This has much to do with the fields formerly used for growing crops that have been flooded to produce electrical power or polluted to the extent that farmers no longer have land to work and water to fish and drink, thus leaving their families in a desperate state constantly fighting for survival. Their fields are now dumping grounds for antiquated computer parts that poison the furrows they once tilled.

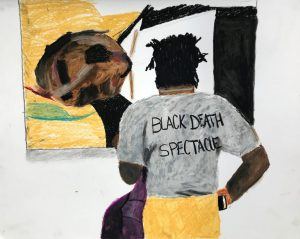

For Chinatown residents, Ji’s paintings may serve as an allegory of what is happening elsewhere; but for Chinese farmers and their families it is reality, one they are forced to confront as an everyday occurrence. In rural China today , extreme poverty has become a fact of life. This has much to do with the fields formerly used for growing crops that have been flooded to produce electrical power or polluted to the extent that farmers no longer have land to work and water to fish and drink, thus leaving their families in a desperate state constantly fighting for survival. Their fields are now dumping grounds for antiquated computer parts that poison the furrows they once tilled. The “urgent recommendation” by Black and her cosignatories that the offending artwork should be destroyed stemmed from a desire to prevent the image of black suffering and death from becoming another commodity; as such, it led to vigorous pushback. Those who rejected the protesters’ positions—people ranging from respected art critics, artists, and art historians, to those who had little interest in art per se but objected to complaints by “snowflake” social-justice warriors on principle—largely framed their counterarguments in terms of free speech, artistic freedom, and censorship. (If we measure the strength of an art-world controversy by how deeply it penetrated into public consciousness, I’d say Whoopi Goldberg telling the protesters they needed to “grow up” on The View ranks this one pretty high. Zadie Smith chalking the controversy up to the “cheap” binary of us vs. them politics in Harper’s Magazine and Coco Fusco writing off not only Hannah Black but the historical black arts movement in Hyperallergic were also telling markers.)

The “urgent recommendation” by Black and her cosignatories that the offending artwork should be destroyed stemmed from a desire to prevent the image of black suffering and death from becoming another commodity; as such, it led to vigorous pushback. Those who rejected the protesters’ positions—people ranging from respected art critics, artists, and art historians, to those who had little interest in art per se but objected to complaints by “snowflake” social-justice warriors on principle—largely framed their counterarguments in terms of free speech, artistic freedom, and censorship. (If we measure the strength of an art-world controversy by how deeply it penetrated into public consciousness, I’d say Whoopi Goldberg telling the protesters they needed to “grow up” on The View ranks this one pretty high. Zadie Smith chalking the controversy up to the “cheap” binary of us vs. them politics in Harper’s Magazine and Coco Fusco writing off not only Hannah Black but the historical black arts movement in Hyperallergic were also telling markers.) Christian Frock in Hyperallergic:

Christian Frock in Hyperallergic: Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lance Taylor over at INET: Philip Roth, the prolific, protean, and often blackly comic novelist who was a pre-eminent figure in 20th century literature, died on Tuesday night at a hospital in Manhattan. He was 85.

Philip Roth, the prolific, protean, and often blackly comic novelist who was a pre-eminent figure in 20th century literature, died on Tuesday night at a hospital in Manhattan. He was 85. Isaac Butler has a new podcast over at Slate on politics and Shakespeare. The first episode is on Julius Caesar:

Isaac Butler has a new podcast over at Slate on politics and Shakespeare. The first episode is on Julius Caesar: Sam Harris, one

Sam Harris, one  James Priest couldn’t make sense of it. He was examining the DNA of a desperately ill baby, searching for a genetic mutation that threatened to stop her heart. But the results looked as if they had come from two different infants.

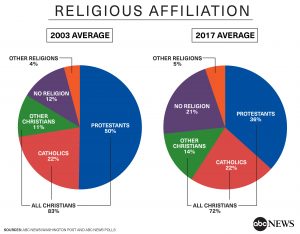

James Priest couldn’t make sense of it. He was examining the DNA of a desperately ill baby, searching for a genetic mutation that threatened to stop her heart. But the results looked as if they had come from two different infants. The nation’s religious makeup has shifted dramatically in the past 15 years, with a sharp drop in the number of Americans who say they’re members of a

The nation’s religious makeup has shifted dramatically in the past 15 years, with a sharp drop in the number of Americans who say they’re members of a