Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New York Times:

On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York.

On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York.

In the mid-2000s, it felt to me, at times, as if cancer medicine were viewing the world from its own Ninth Avenue. Our collective vision was dominated by genomics — by the newfound capacity to sequence the genomes of cells (a “genome” refers to the complete set of genetic material present in an organism or a cell). Cancer, of course, is typically a disease caused by mutant genes that drive abnormal cellular growth (other features of cellular physiology, like the cell’s metabolism and survival, are also affected). By identifying the mutant genes in cancer cells, the logic ran, we would devise new ways of killing the cells. And because the exact set of mutations was unique to an individual patient — one woman’s breast cancer might have mutations in 12 genes, while another breast cancer might have mutations in a different set of 16 — we would “personalize” cancer medicine to that patient, thereby vastly increasing the effectiveness of therapy.

This kind of thinking had an exhilarating track record. In the 2000s, a medicine called Herceptin was shown to be effective for women with breast cancer, but only if the cancer cells carried a genetic aberration in a gene called HER-2. Another drug, Gleevec, worked only if the tumor cells had a mutant gene called BCR-ABL, or a mutation in a gene called c-kit. In many of our genome-obsessed minds, the problem of cancer had become reduced to a rather simple, scalable algorithm: find the mutations in a patient, and match those mutations with a medicine. All the other variables — the cellular environment within which the cancer cell was inescapably lodged, the metabolic and hormonal milieu that surrounded the cancer or, for that matter, the human body that was wrapped around it — might as well have been irrelevant blobs receding in the distance: Japan, China, Russia.

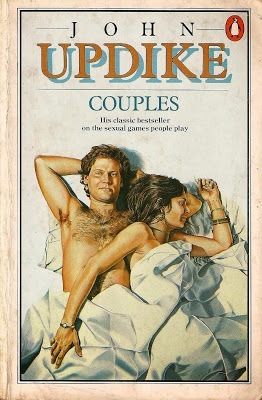

By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.”

By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.” The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that

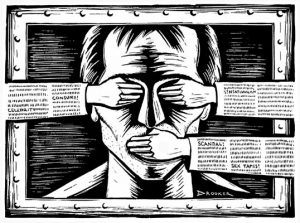

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that  Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government.

Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government. It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy?

It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy? The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature. If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

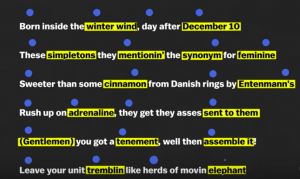

If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts.

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts. And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them.

And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them. Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal.

Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal. If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights.

If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights. Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet

Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet  Earlier this week,

Earlier this week,  In a famous Hindu parable, three blind men encounter an elephant for the first time and try to describe it, each touching a different part. “An elephant is like a snake,” says one, grasping the trunk. “Nonsense; an elephant is a fan,” says another, who holds an ear. “A tree trunk,” insists a third, feeling his way around a leg.

In a famous Hindu parable, three blind men encounter an elephant for the first time and try to describe it, each touching a different part. “An elephant is like a snake,” says one, grasping the trunk. “Nonsense; an elephant is a fan,” says another, who holds an ear. “A tree trunk,” insists a third, feeling his way around a leg.