Scott Samuelson in Aeon:

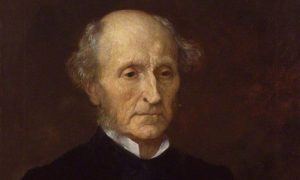

In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.

In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.

The young Mill soldiered on with efforts for social reform, but his heart wasn’t in it. He’d become a utilitarian machine with a suicidal ghost inside. With his well-tuned calculative abilities, the despairing philosopher put his finger right on the problem:

[I]t occurred to me to put the question directly to myself: ‘Suppose that all your objects in life were realised; that all the changes in institutions and opinions which you are looking forward to could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?’ And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered: ‘No!’ At this my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my life was constructed fell down.

For most of our history, we’ve seen suffering as a mystery, and dealt with it by placing it in a complex symbolic framework, often where this life is conceived as a testing ground. In the 18th century, the mystery of suffering becomes the ‘problem of evil’, in which pain and misery turn into clear-cut refutations of God’s goodness to utilitarian reformers. As Mill says of his father: ‘He found it impossible to believe that a world so full of evil was the work of an Author combining infinite power with perfect goodness and righteousness.’

For a utilitarian, the idea of worshipping the creator of suffering is not only absurd, it undercuts the purpose of morality. It channels our energies toward the acceptance of what we should remedy. To revere the natural order could even turn us into moral monsters. Mill says: ‘In sober truth, nearly all the things which men are hanged or imprisoned for doing to one another, are nature’s every day performances.’ What Mill calls the ‘Religion of Humanity’ involves pushing aside the old conception of God, and taking over responsibility for what happens in the world. We’re to become the good architect that God never was.

More here.