David Klion in The Ideas Letter:

Liberalism has never been merely a set of abstract ideas, and it has never been uniformly experienced within the liberal polity. As Antonio Gramsci observed, cultural hegemony allows the bourgeoisie to maintain its dominant position in society by creating a broad social consensus around its own norms and values, and very often those norms and values have been liberal. Liberalism has always been the ideology of a particular socioeconomic stratum: from the Parisian haute bourgeoisie that declared the Rights of Man in the late 18th century to the New Class of college-educated intellectuals, professionals, and creatives that by the 1970s had come to dominate liberalism in the United States—at least according to its many critics. James Burnham anticipated capitalism’s managerial turn as early as 1941. Christopher Lasch, in his posthumously published 1995 book The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, criticized upper-middle-class groups as having alienated themselves materially and culturally from the rest of the population, describing them as “a new class only in the sense that their livelihoods rest not so much on ownership of property as on the manipulation of information and professional expertise.” The right-wing ideologue Curtis Yarvin, a court favorite of Vice President J.D. Vance and the Silicon Valley oligarch Marc Andreessen, calls this cohort “the cathedral.” Nate Silver has dubbed it “the Village.” Musa al-Gharbi, who recently responded in The Ideas Letter to a critical review of his book We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, has described approximately the same group as “symbolic capitalists—professionals who work in fields like finance, consulting, law, HR, education, media, science and technology.” Less hostile observers might simply say “the establishment” or “liberal civil society” or, as Barbara and John Ehrenreich put it in 1977, “the professional-managerial class.”

It is a version of this class that lives and breathes liberalism and forms its core constituency in any given place and time. And it is this class that is under sustained assault from all directions right now, with both corporate capital and much of the lumpenproletariat targeting its prevailing fashions (often cast as “wokeness”) and the rights (media and academic freedom, the rule of law) that undergird the material basis of its influence (government bureaucracies, elite universities, publishing houses, legacy newspapers and magazines, the entertainment industry). Across many countries, the authority and autonomy of the liberal class is being challenged and undermined; on every front, the liberal class faces precarity, professional frustration, and ambient despair over the state of the culture

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Rina Green calls her “living hell” began with an innocuous backache. By late 2022, two years later, pain flooded her entire body daily and could be so intense that she couldn’t get out of bed. Painkillers and physical therapy offered little relief. She began using a wheelchair.

What Rina Green calls her “living hell” began with an innocuous backache. By late 2022, two years later, pain flooded her entire body daily and could be so intense that she couldn’t get out of bed. Painkillers and physical therapy offered little relief. She began using a wheelchair.

L

L Parenting teenagers

Parenting teenagers In the Preface to his landmark Dictionary of 1755, Samuel Johnson wrote that ‘sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride’. Any dictionary, any grammar, is but a snapshot: all living languages change, and they do so constantly and at every level.

In the Preface to his landmark Dictionary of 1755, Samuel Johnson wrote that ‘sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride’. Any dictionary, any grammar, is but a snapshot: all living languages change, and they do so constantly and at every level. Like many proud parents,

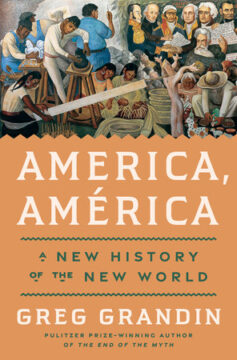

Like many proud parents,  “America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning

“America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning  We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought.

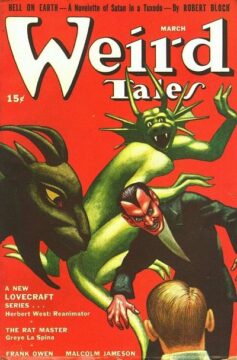

We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought. A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it.

A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it. The Trump administration

The Trump administration  Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.”

Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.”