John Rosenthal in The Hedgehog Review:

I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera.

I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of  It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best.

It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best. B

B We all want

We all want GILLIAN CARNEGIE’S current show at

GILLIAN CARNEGIE’S current show at  In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in

In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in  In the early months of 1966, whenever Paul McCartney sat down at a piano, wherever it was, he would start tinkering with a song he called “Miss Daisy Hawkins.” From the moment he found its first five syllabic notes, the song seems to have found its themes: loneliness, futility, the end of life. McCartney was twenty-three. Without discussing it, both John Lennon and Paul came back from their break with songs about death, written from a detached, omniscient perspective.

In the early months of 1966, whenever Paul McCartney sat down at a piano, wherever it was, he would start tinkering with a song he called “Miss Daisy Hawkins.” From the moment he found its first five syllabic notes, the song seems to have found its themes: loneliness, futility, the end of life. McCartney was twenty-three. Without discussing it, both John Lennon and Paul came back from their break with songs about death, written from a detached, omniscient perspective. Sixty years ago, a debate raged between two titans of evolutionary biology that came to be

Sixty years ago, a debate raged between two titans of evolutionary biology that came to be  Inflation is, at base, a tax on consumption – and it hits the poor the hardest, since they consume more of their incomes and the rich consume less.

Inflation is, at base, a tax on consumption – and it hits the poor the hardest, since they consume more of their incomes and the rich consume less. Sometime in the next several months, a team of US scientists plans to pour a solution of antacid into the waves off the coast of Massachusetts. Using boats, buoys and autonomous gliders, the scientists will track changes in water chemistry that should allow this tiny patch of the Atlantic Ocean to absorb more carbon dioxide from the sky than it normally would.

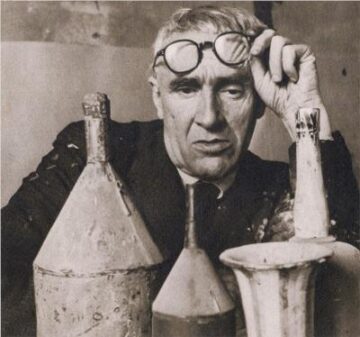

Sometime in the next several months, a team of US scientists plans to pour a solution of antacid into the waves off the coast of Massachusetts. Using boats, buoys and autonomous gliders, the scientists will track changes in water chemistry that should allow this tiny patch of the Atlantic Ocean to absorb more carbon dioxide from the sky than it normally would. It’s been an exceptionally rich decade for fans of the great mid-century Italian master Giorgio Morandi here in New York City, beginning with the superb retrospective at the Metropolitan back in 2008 (which I’ve already referenced in the pages of this Cabinet back in

It’s been an exceptionally rich decade for fans of the great mid-century Italian master Giorgio Morandi here in New York City, beginning with the superb retrospective at the Metropolitan back in 2008 (which I’ve already referenced in the pages of this Cabinet back in