Hilton Als in The New Yorker:

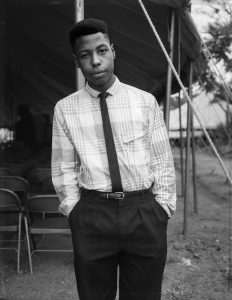

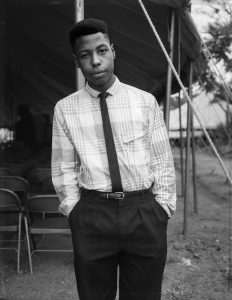

He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with.

He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with.

In those family members’ eyes—the eyes of love, of complicated fraternity—he is a very real thing, attached to names given by parents or mothers or grandparents. Every name comes with a story dear to those who have bestowed it on the generations that come after, just as people attached great importance to Michael’s name, and Eric’s name, and Samuel’s name. In the library, he struggled to find the love and meaning in his own real name, since so many people said he was invisible. He’d once read that, years ago, Toni Morrison, when asked her opinion of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” had said that, while she was unqualified in her praise of Ellison’s artistry, one question remained, hung fire: Who was he invisible to? Not to her. He was her brother, her father, her friend, and now, looking at Bey’s lens, he conveyed the satisfaction of being seen, which is a form of brotherhood and love, too.

More here.

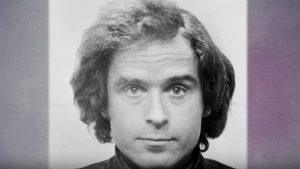

When Ted Bundy was apprehended in Pensacola in the early hours of February 15, 1978, six weeks after he escaped from a Colorado jail, the FBI had already publicly linked him to thirty-six murders across five states. In the ensuing decade, both the random speculations of onlookers and the educated guesses of law enforcement often pushed the number far higher. Many said it had to be a hundred or more, and cited Bundy’s own enigmatic statement to the Pensacola detectives who had questioned him about the FBI’s claim. “He said the figure probably would be more correct in the three digits,” Deputy Sheriff Jack Poitinger said.

When Ted Bundy was apprehended in Pensacola in the early hours of February 15, 1978, six weeks after he escaped from a Colorado jail, the FBI had already publicly linked him to thirty-six murders across five states. In the ensuing decade, both the random speculations of onlookers and the educated guesses of law enforcement often pushed the number far higher. Many said it had to be a hundred or more, and cited Bundy’s own enigmatic statement to the Pensacola detectives who had questioned him about the FBI’s claim. “He said the figure probably would be more correct in the three digits,” Deputy Sheriff Jack Poitinger said.

Amid all the hot, languid days of late August, melting together into a lifetime’s haze of forgotten moments, what happened exactly a half-century ago will never fade: I’m tightly holding the hand of a girl I’ve only just met, fleeing the searing sensation of tear gas, coughing and wheezing, caught up in the crowd stampeding out of Grant Park down Michigan Avenue.

Amid all the hot, languid days of late August, melting together into a lifetime’s haze of forgotten moments, what happened exactly a half-century ago will never fade: I’m tightly holding the hand of a girl I’ve only just met, fleeing the searing sensation of tear gas, coughing and wheezing, caught up in the crowd stampeding out of Grant Park down Michigan Avenue. He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with.

He opened a book of Dawoud Bey’s photographs at random. The images were of people of color, not unlike himself, and what he loved about the images was how the subjects held their own self-validation in their hands, their eyes, without being reduced to an ideology—you know, equating blackness with nobility, that kind of thing. It was such a relief, to see works of art made out of real lives. The pictures named a world he knew, even as he struggled to understand it more. And, even though the pictures hadn’t been shot in Ferguson, Staten Island, or Cincinnati, they shimmered with lives—black male lives. Generally, the language around that familiar and unfamiliar form has little to do with his humanity and more to do with the pressure points—guilt, remorse, and so on—his dead or living self aggravates. And, because he’s less interesting in the context of joy, the continued violence to his body. Under his white shirt, he knew something about that. And this: that the violence inflicted on the black male body didn’t stop there but extended, of course, to his community, which includes mothers and brothers and all the people who never considered him invisible or trivial or tragic or extinguishable to begin with. Let’s be optimistic and assume that we manage to avoid a self-inflicted nuclear holocaust, an extinction-sized asteroid, or deadly irradiation from a nearby supernova. That leaves about 6 billion years until the sun turns into a red giant, swelling to the orbit of Earth and melting our planet. Sounds like a lot of time. But don’t get too relaxed. Doomsday is coming a lot sooner than that. The Earth is, in some ways, in a precarious spot in the solar system. There’s a range of orbital distances inside which a planet can have both liquid surface water (which is believed to be necessary for life) and enough atmospheric CO2 to carry on photosynthesis. This range is called the photosynthesis habitable zone. The Earth orbits barely within the sun’s zone. Some scientists estimate that the inner edge lies just 7.5 million kilometers away, which is only 5 percent of the distance between the Earth and the sun.

Let’s be optimistic and assume that we manage to avoid a self-inflicted nuclear holocaust, an extinction-sized asteroid, or deadly irradiation from a nearby supernova. That leaves about 6 billion years until the sun turns into a red giant, swelling to the orbit of Earth and melting our planet. Sounds like a lot of time. But don’t get too relaxed. Doomsday is coming a lot sooner than that. The Earth is, in some ways, in a precarious spot in the solar system. There’s a range of orbital distances inside which a planet can have both liquid surface water (which is believed to be necessary for life) and enough atmospheric CO2 to carry on photosynthesis. This range is called the photosynthesis habitable zone. The Earth orbits barely within the sun’s zone. Some scientists estimate that the inner edge lies just 7.5 million kilometers away, which is only 5 percent of the distance between the Earth and the sun. John Rawls was one of the twentieth century’s preeminent liberal philosophers. His major work,

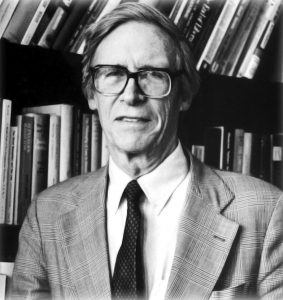

John Rawls was one of the twentieth century’s preeminent liberal philosophers. His major work,  The speed with which campus life has changed for the worse is one of the most important points made by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in this important if disturbing book. Lukianoff is a lawyer and head of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), which works to protect academic freedom. Haidt is a professor of social psychology at NYU’s Stern School of Business and the founder of Heterodox Academy, which promotes intellectual diversity in academic life — the one type of diversity that universities appear not to care about.

The speed with which campus life has changed for the worse is one of the most important points made by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in this important if disturbing book. Lukianoff is a lawyer and head of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), which works to protect academic freedom. Haidt is a professor of social psychology at NYU’s Stern School of Business and the founder of Heterodox Academy, which promotes intellectual diversity in academic life — the one type of diversity that universities appear not to care about. While the recent Heterodox Psychology conference in southern California was filled with highlights, for me, the keynote address by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, two pioneers in the field of

While the recent Heterodox Psychology conference in southern California was filled with highlights, for me, the keynote address by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, two pioneers in the field of  Moore was not alone in her writerly affinity with Pratt’s art. Pratt’s Wedding Dress graced the cover of Alice Munro’s 1990 short story collection Friend of My Youth. The late Diana Brebner won the

Moore was not alone in her writerly affinity with Pratt’s art. Pratt’s Wedding Dress graced the cover of Alice Munro’s 1990 short story collection Friend of My Youth. The late Diana Brebner won the  Prior to her death from breast cancer in 1997, Kathy Acker wrote critically on the normative and hegemonic discourses and structures surrounding gender and sexuality, the (feminised) body, and taboos, in particular of sex, pornography and abjected beings. Through the female characters in her novels she explored and situated her own sexed and gendered positionality within systems of power and disciplinary, totalitarian violence. Acker was heralded and criticised for challenging traditional literary conventions, melding the boundaries of fiction, poetry, essay and diary writing or epistolary, of high-brow and low-brow, or as she called it “Schlock”, as well as the distinctions between literature and art. She has often been labelled a writer of the postmodern era, or, at worst, confined as a female literary offspring of William S. Burroughs or David Antin, Charles Olson and other Black Mountain Poets. Yes Acker did plagiarise or “cut-up” existing works, describing it as a crisis of voice as well as a (tactic of guerilla warfare, in the use of fictions, of language). Her Fathers told her to find her own voice, or in other words, to find and then sell her soul; although not as the stuff of essence or transcendent energy, but the individualised Cartesian soul, aka the mind.

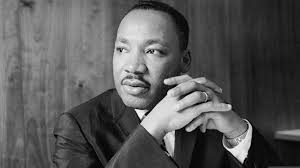

Prior to her death from breast cancer in 1997, Kathy Acker wrote critically on the normative and hegemonic discourses and structures surrounding gender and sexuality, the (feminised) body, and taboos, in particular of sex, pornography and abjected beings. Through the female characters in her novels she explored and situated her own sexed and gendered positionality within systems of power and disciplinary, totalitarian violence. Acker was heralded and criticised for challenging traditional literary conventions, melding the boundaries of fiction, poetry, essay and diary writing or epistolary, of high-brow and low-brow, or as she called it “Schlock”, as well as the distinctions between literature and art. She has often been labelled a writer of the postmodern era, or, at worst, confined as a female literary offspring of William S. Burroughs or David Antin, Charles Olson and other Black Mountain Poets. Yes Acker did plagiarise or “cut-up” existing works, describing it as a crisis of voice as well as a (tactic of guerilla warfare, in the use of fictions, of language). Her Fathers told her to find her own voice, or in other words, to find and then sell her soul; although not as the stuff of essence or transcendent energy, but the individualised Cartesian soul, aka the mind. I hadn’t appreciated how important the idea of dignity is to his thought. It structures his critique of the limits placed on human liberty and opportunity by Jim Crow, and his objections to the impoverishment and ghettoization of northern black people. Maybe I also I hadn’t appreciated some of the more pragmatic features of his thought. It’s easy to see King as an idealist, but there’s a strong streak of realism in his work. He’s thinking very hard about what forms of political pressure one must bring to bear in order to realize the most fundamental ideals and principles. There’s a lot of focus on psychology, on diagnosing the mindset of allies and opponents. People often imagine that as a Christian minister he was aligned with moral suasion as the principal means of realizing his political ideals, and neglect the other forms of political maneuvering that are central to his thought.

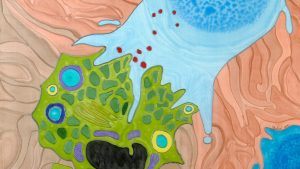

I hadn’t appreciated how important the idea of dignity is to his thought. It structures his critique of the limits placed on human liberty and opportunity by Jim Crow, and his objections to the impoverishment and ghettoization of northern black people. Maybe I also I hadn’t appreciated some of the more pragmatic features of his thought. It’s easy to see King as an idealist, but there’s a strong streak of realism in his work. He’s thinking very hard about what forms of political pressure one must bring to bear in order to realize the most fundamental ideals and principles. There’s a lot of focus on psychology, on diagnosing the mindset of allies and opponents. People often imagine that as a Christian minister he was aligned with moral suasion as the principal means of realizing his political ideals, and neglect the other forms of political maneuvering that are central to his thought. When you think of sugar, you probably think of the sweet, white, crystalline table sugar that you use to make cookies or sweeten your coffee. But did you know that within our body, simple sugar molecules can be connected together to create powerful structures that have recently been found to be linked to health problems, including cancer, aging and autoimmune diseases. These long sugar chains that cover each of our cells are called glycans, and according to the National Academy of Sciences, creating a map of their location and structure will

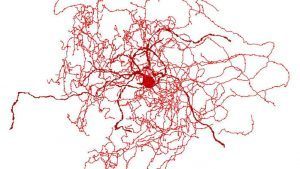

When you think of sugar, you probably think of the sweet, white, crystalline table sugar that you use to make cookies or sweeten your coffee. But did you know that within our body, simple sugar molecules can be connected together to create powerful structures that have recently been found to be linked to health problems, including cancer, aging and autoimmune diseases. These long sugar chains that cover each of our cells are called glycans, and according to the National Academy of Sciences, creating a map of their location and structure will  In a mysterious addition to the brain’s family of cells, researchers have discovered a new kind of neuron—a dense, bushy bundle (above) that is present in people but seems to be missing in mice. These “rosehip neurons,” were found in the uppermost layer of the cortex, which is home to many different types of neurons that inhibit the activity of other neurons. Scientists spotted the neurons in slices of human brain tissue as part of a larger effort to inventory human brain cells by combining microscopic study of brain anatomy and the genetic analysis of individual cells. The cells were small and compact, with a dense, bushy shape. At the points along their projections where they transmit signals to other cells—called axonal boutons—they had unusually large, bulbous structures, which inspired their name.

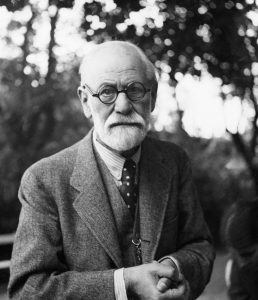

In a mysterious addition to the brain’s family of cells, researchers have discovered a new kind of neuron—a dense, bushy bundle (above) that is present in people but seems to be missing in mice. These “rosehip neurons,” were found in the uppermost layer of the cortex, which is home to many different types of neurons that inhibit the activity of other neurons. Scientists spotted the neurons in slices of human brain tissue as part of a larger effort to inventory human brain cells by combining microscopic study of brain anatomy and the genetic analysis of individual cells. The cells were small and compact, with a dense, bushy shape. At the points along their projections where they transmit signals to other cells—called axonal boutons—they had unusually large, bulbous structures, which inspired their name. Originally, Freud analyzed only himself, and did so for five years, but he grew exhausted running back and forth between his chair and the couch. He then came up with the idea of analyzing patients, and continued to do so for the rest of his life. At first, Freud sat on the couch and the patient sat at his desk, but he changed places after discovering that his pens were disappearing.

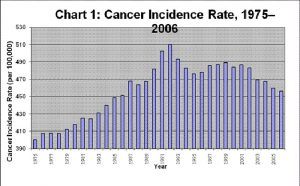

Originally, Freud analyzed only himself, and did so for five years, but he grew exhausted running back and forth between his chair and the couch. He then came up with the idea of analyzing patients, and continued to do so for the rest of his life. At first, Freud sat on the couch and the patient sat at his desk, but he changed places after discovering that his pens were disappearing. Official statistics say we are winning the War on Cancer. Cancer incidence rates, mortality rates, and five-year-survival rates have generally been moving in the right direction over the past few decades.

Official statistics say we are winning the War on Cancer. Cancer incidence rates, mortality rates, and five-year-survival rates have generally been moving in the right direction over the past few decades. Throughout most of American history, the idea of socialism has been a hopeless, often vaguely defined dream. So distant were its prospects at midcentury that the best definition Irving Howe and Lewis Coser, editors of the socialist periodical Dissent, could come up with in 1954 was this: “Socialism is the name of our desire.”

Throughout most of American history, the idea of socialism has been a hopeless, often vaguely defined dream. So distant were its prospects at midcentury that the best definition Irving Howe and Lewis Coser, editors of the socialist periodical Dissent, could come up with in 1954 was this: “Socialism is the name of our desire.” A mostly overlooked component of

A mostly overlooked component of