Scotty Hendricks in Big Think:

Here’s a fun experiment to try. Go to your pantry and see if you have a box of spaghetti. If you do, take out a noodle. Grab both ends of it and bend it until it breaks in half. How many pieces did it break into? If you got two large pieces and at least one small piece you’re not alone.

Here’s a fun experiment to try. Go to your pantry and see if you have a box of spaghetti. If you do, take out a noodle. Grab both ends of it and bend it until it breaks in half. How many pieces did it break into? If you got two large pieces and at least one small piece you’re not alone.

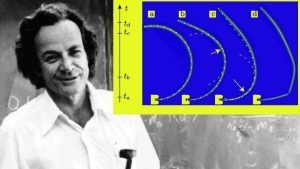

Richard Feynman, world-class physicist, bongo player, and writer of letters, once spent an evening trying to break spaghetti into two pieces by bending it at both ends. After hours spent in the kitchen and a great deal of pasta having been wasted, he and his friend Danny Hillis admitted defeat. Even worse, they had no solution for why the spaghetti always broke into at least three pieces.

The mystery remained unsolved until 2005, when French scientists Basile Audoly and Sebastien Neukirch won an Ig Nobel Prize, an award given to scientists for real work which is of a less serious nature than the discoveries that win Nobel prizes, for finally determining why this happens. Their paper describing the effect is wonderfully funny to read, as it takes such a banal issue so seriously.

They demonstrated that when a rod is bent past a certain point, such as when spaghetti is snapped in half by bending it at the ends, a “snapback effect” is created. This causes energy to reverberate from the initial break to other parts of the rod, often leading to a second break elsewhere.

While this settled the issue of why spaghetti noodles break into three or more pieces, it didn’t establish if they always had to break this way. The question of if the snapback could be regulated remained unsettled.

More here.

The Republican political consultant

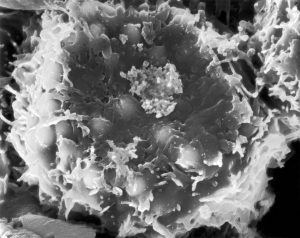

The Republican political consultant  Drugs that activate the immune system to fight cancer have brought remarkable recoveries to many people in recent years. But one of those drugs seems to have had the opposite effect on three patients with an uncommon blood cancer who were taking part in a study. After a single treatment, their disease quickly became much worse, doctors reported in a

Drugs that activate the immune system to fight cancer have brought remarkable recoveries to many people in recent years. But one of those drugs seems to have had the opposite effect on three patients with an uncommon blood cancer who were taking part in a study. After a single treatment, their disease quickly became much worse, doctors reported in a  McCarthy’s fiction, collected by the Library of America in two new volumes, shows how her preoccupation with factuality shaped her art. The collection includes all seven of her novels—the first published in 1942, the last in 1979—as well as collected and uncollected stories and an essay on “the novels that got away.” Through it all, we see McCarthy’s fixation on the surface details that distinguish class and character: a middle-aged man from the Midwest who is given to wearing Brooks Brothers suits; a Yale man working at a leftist magazine who sports a “well-cut brown suit that needed pressing”; bohemian couples living on Cape Cod who drink too much and don’t bother keeping house. We learn that it was a status symbol in 1930s New York for a Vassar graduate to serve coffee with real cream.

McCarthy’s fiction, collected by the Library of America in two new volumes, shows how her preoccupation with factuality shaped her art. The collection includes all seven of her novels—the first published in 1942, the last in 1979—as well as collected and uncollected stories and an essay on “the novels that got away.” Through it all, we see McCarthy’s fixation on the surface details that distinguish class and character: a middle-aged man from the Midwest who is given to wearing Brooks Brothers suits; a Yale man working at a leftist magazine who sports a “well-cut brown suit that needed pressing”; bohemian couples living on Cape Cod who drink too much and don’t bother keeping house. We learn that it was a status symbol in 1930s New York for a Vassar graduate to serve coffee with real cream.

The

The Pankaj Mishra and Nikil Saval discuss V.S. Naipaul in n+1:

Pankaj Mishra and Nikil Saval discuss V.S. Naipaul in n+1: Few nations have been as obsessed with their status in the world as Great Britain. Not surprisingly, the

Few nations have been as obsessed with their status in the world as Great Britain. Not surprisingly, the

From the start of the Russia investigation, President Trump has been working to discredit the work and the integrity of the special counsel, Robert Mueller; praising men who are blatant grifters, cons and crooks; insisting that he’s personally done nothing wrong; and reminding us that he hires only the best people.

From the start of the Russia investigation, President Trump has been working to discredit the work and the integrity of the special counsel, Robert Mueller; praising men who are blatant grifters, cons and crooks; insisting that he’s personally done nothing wrong; and reminding us that he hires only the best people. Quantum mechanics and general relativity are the two great triumphs of twentieth-century theoretical physics. Unfortunately, they don’t play well together — despite years of effort, we currently lack a completely successful quantum theory of gravity, although there are some promising ideas out there. Carlo Rovelli is a pioneer of one of those ideas, loop quantum gravity, as well as the bestselling author of such books as

Quantum mechanics and general relativity are the two great triumphs of twentieth-century theoretical physics. Unfortunately, they don’t play well together — despite years of effort, we currently lack a completely successful quantum theory of gravity, although there are some promising ideas out there. Carlo Rovelli is a pioneer of one of those ideas, loop quantum gravity, as well as the bestselling author of such books as  Arsenic

Arsenic It’s a hot and humid afternoon in the suburbs of Washington DC, and Bob Watson is looking worried. The renowned atmospheric chemist sits back on a bench in his yard, hemmed in by piles of paperwork. He speaks with his characteristic rapid-fire delivery as he explains the tensions surrounding the international committee he helms. The panel is supposed to provide scientific advice on one of the world’s most intractable problems — the

It’s a hot and humid afternoon in the suburbs of Washington DC, and Bob Watson is looking worried. The renowned atmospheric chemist sits back on a bench in his yard, hemmed in by piles of paperwork. He speaks with his characteristic rapid-fire delivery as he explains the tensions surrounding the international committee he helms. The panel is supposed to provide scientific advice on one of the world’s most intractable problems — the  On the northwestern edge of Los Angeles, where I grew up, the wildfires came in late summer. We lived in a new subdivision, and behind our house were the hills, golden and parched. We would hose down the wood-shingled roof as fire crews bivouacked in our street. Our neighborhood never burned, but others did. In the Bel Air fire of 1961, nearly five hundred homes burned, including those of Burt Lancaster and Zsa Zsa Gabor. We were all living in the “wildland-urban interface,” as it is now called. More subdivisions were built, farther out, and for my family the wildfire threat receded.

On the northwestern edge of Los Angeles, where I grew up, the wildfires came in late summer. We lived in a new subdivision, and behind our house were the hills, golden and parched. We would hose down the wood-shingled roof as fire crews bivouacked in our street. Our neighborhood never burned, but others did. In the Bel Air fire of 1961, nearly five hundred homes burned, including those of Burt Lancaster and Zsa Zsa Gabor. We were all living in the “wildland-urban interface,” as it is now called. More subdivisions were built, farther out, and for my family the wildfire threat receded. Last year, I did what 12 million people from all over the world have done and surrendered my spit to a home DNA-testing company. I hoped a

Last year, I did what 12 million people from all over the world have done and surrendered my spit to a home DNA-testing company. I hoped a  Agnes Heller*: I do not like the term populist as it is used in the context of Viktor Orban, because it does not say anything. Populists rely typically on poor people. Orban uses nationalistic vocabulary and rhetoric, he mobilizes hatred against the stranger and the alien, but it has nothing to do with populism. It has to do with the right-wing, but this is also questionable, because Orban is a man who is interested only in power.

Agnes Heller*: I do not like the term populist as it is used in the context of Viktor Orban, because it does not say anything. Populists rely typically on poor people. Orban uses nationalistic vocabulary and rhetoric, he mobilizes hatred against the stranger and the alien, but it has nothing to do with populism. It has to do with the right-wing, but this is also questionable, because Orban is a man who is interested only in power.