Jason Stanley in the Boston Review:

What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail?

What are the limits of freedom of speech? It is a pressing question at a moment when conspiracy theories help to fuel fascist politics around the world. Shouldn’t liberal democracy promote a full airing of all possibilities, even false and bizarre ones, because the truth will eventually prevail?

Perhaps philosophy’s most famous defense of the freedom of speech was articulated by John Stuart Mill, who defended the ideal in his 1859 work, On Liberty. In chapter 2, “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” Mill argues that silencing any opinion is wrong, even if the opinion is false, because knowledge arises only from the “collision [of truth] with error.” In other words, true belief becomes knowledge only by emerging victorious from the din of argument and discussion, which must occur either with actual opponents or through internal dialogue. Without this process, even true belief remains mere “prejudice.” We must allow all speech, even defense of false claims and conspiracy theories, because it is only then that we have a chance of achieving knowledge.

Rightly or wrongly, many associate Mill’s On Liberty with the motif of a “marketplace of ideas,” a realm that, if left to operate on its own, will drive out prejudice and falsehood and produce knowledge. But this notion, like that of a free market generally, is predicated on a utopian conception of consumers.

More here.

Jazz occupies a special place in the American cultural landscape. It’s played in elegant concert halls and run-down bars, and can feature esoteric harmonic experimentation or good old-fashioned foot-stomping swing. Nobody embodies the scope of modern jazz better than Wynton Marsalis. As a trumpet player, bandleader, composer, educator, and ambassador for the music, he has worked tirelessly to keep jazz vibrant and alive. In this bouncy conversation, we talk about various kinds of music, how they might relate to physics, and some of the greater challenges facing the United States today.

Jazz occupies a special place in the American cultural landscape. It’s played in elegant concert halls and run-down bars, and can feature esoteric harmonic experimentation or good old-fashioned foot-stomping swing. Nobody embodies the scope of modern jazz better than Wynton Marsalis. As a trumpet player, bandleader, composer, educator, and ambassador for the music, he has worked tirelessly to keep jazz vibrant and alive. In this bouncy conversation, we talk about various kinds of music, how they might relate to physics, and some of the greater challenges facing the United States today. When people ask about my religion I usually just say I’m an atheist and I have no religion. If they continue, I usually give them what they want, and state my parents are Muslim, or I am from a Muslim background (most of the time the people asking for what it’s worth are themselves Muslims, or from a Muslim background, or, not American). I never say that I used to be a Muslim because that’s really not true.

When people ask about my religion I usually just say I’m an atheist and I have no religion. If they continue, I usually give them what they want, and state my parents are Muslim, or I am from a Muslim background (most of the time the people asking for what it’s worth are themselves Muslims, or from a Muslim background, or, not American). I never say that I used to be a Muslim because that’s really not true. Book Six brings My Struggle, after 3,600 pages, to an end. And so it has been subtitled, ominously—“The End.” Here, the writer who writes (and writes) about himself must write about that experience, too, and we duly find out what dinner-table conversation was like at the home of that very determined Norwegian who, between 2007 and 2011, got up at 4:30 am every weekday, sat down to his desktop computer in Malmö, Sweden, and for a few hours did his best to mention in print all that was unmentionable about his life, stopping only when his three small children woke up and demanded he make them breakfast. Book Six tells this story: the struggle behind the Struggle. No one will be shocked to discover that all the prizes and praise have only brought Karl Ove more pain. There’s also the small problem of having linked his name for all time with you-know-who. “Turns out he’s read Mein Kampf,” as his then-wife, Linda Boström, tells him of a new friend. “Hitler’s, that is.” She met her friend at the Malmö mental hospital. She went there voluntarily not long after reading Book Two, among whose radical aesthetic moves was a scene recalling the time Karl Ove got drunk and tried to cheat on her. “It’s always struck me that I was a sailor’s wife,” she tells him. “But now it’s the other way around. Now I’m the sailor.”

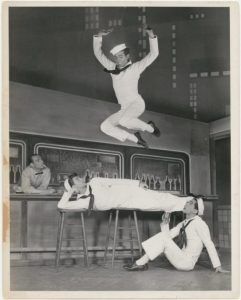

Book Six brings My Struggle, after 3,600 pages, to an end. And so it has been subtitled, ominously—“The End.” Here, the writer who writes (and writes) about himself must write about that experience, too, and we duly find out what dinner-table conversation was like at the home of that very determined Norwegian who, between 2007 and 2011, got up at 4:30 am every weekday, sat down to his desktop computer in Malmö, Sweden, and for a few hours did his best to mention in print all that was unmentionable about his life, stopping only when his three small children woke up and demanded he make them breakfast. Book Six tells this story: the struggle behind the Struggle. No one will be shocked to discover that all the prizes and praise have only brought Karl Ove more pain. There’s also the small problem of having linked his name for all time with you-know-who. “Turns out he’s read Mein Kampf,” as his then-wife, Linda Boström, tells him of a new friend. “Hitler’s, that is.” She met her friend at the Malmö mental hospital. She went there voluntarily not long after reading Book Two, among whose radical aesthetic moves was a scene recalling the time Karl Ove got drunk and tried to cheat on her. “It’s always struck me that I was a sailor’s wife,” she tells him. “But now it’s the other way around. Now I’m the sailor.” At the tender age of 25, Robbins made his first splash as a choreographer with a story ballet about three sailors on shore leave. The thirst for beer, adventure, and women brings out the primal urges of youth. Aptly titled

At the tender age of 25, Robbins made his first splash as a choreographer with a story ballet about three sailors on shore leave. The thirst for beer, adventure, and women brings out the primal urges of youth. Aptly titled  “My experiences in the First World War have haunted me all my life,” Edmund Blunden confessed the year before he died, “and for many days I have, it seemed, lived in that world rather than this.” Siegfried Sassoon felt much the same, and despite producing many volumes of verse on other topics both men would continue to be fêted as war poets.

“My experiences in the First World War have haunted me all my life,” Edmund Blunden confessed the year before he died, “and for many days I have, it seemed, lived in that world rather than this.” Siegfried Sassoon felt much the same, and despite producing many volumes of verse on other topics both men would continue to be fêted as war poets. Paul Scott, author of The Jewel in the Crown (1966), said of India: “It was mysteriously in our blood and perhaps still is.” Despite the comparatively small number of British who actually went there – in 1901, at the height of the Raj, there were only about 155,000 in the subcontinent – there was an extraordinary bond. Some families didn’t come home for centuries, but stayed in India “generation after generation, as dolphins follow in line across the open sea,” as Kipling put it. David Gilmour, author of Curzon (1994) and The Ruling Caste (2005), has tackled this rich history in The British in India, from the granting of the East India Company’s charter in 1600 to the mid-1960s, when the hippy invasion began. Although the chronology is never in doubt, his treatment is grouped by topic – intimacies, formalities, voyages, working life, and so on. The result is somewhat like a tapestry.

Paul Scott, author of The Jewel in the Crown (1966), said of India: “It was mysteriously in our blood and perhaps still is.” Despite the comparatively small number of British who actually went there – in 1901, at the height of the Raj, there were only about 155,000 in the subcontinent – there was an extraordinary bond. Some families didn’t come home for centuries, but stayed in India “generation after generation, as dolphins follow in line across the open sea,” as Kipling put it. David Gilmour, author of Curzon (1994) and The Ruling Caste (2005), has tackled this rich history in The British in India, from the granting of the East India Company’s charter in 1600 to the mid-1960s, when the hippy invasion began. Although the chronology is never in doubt, his treatment is grouped by topic – intimacies, formalities, voyages, working life, and so on. The result is somewhat like a tapestry. In a study carried out over the summer, a group of volunteers drank a white, peppermint-ish concoction laced with billions of bacteria. The microbes had been engineered to break down a naturally occurring toxin in the blood. The vast majority of us can do this without any help. But for those who cannot, these microbes may someday become a living medicine. The trial marks an important milestone in a promising scientific field known as synthetic biology. Two decades ago, researchers started to tinker with living things the way engineers tinker with electronics. They took advantage of the fact that genes typically don’t work in isolation. Instead, many genes work together, activating and deactivating one another. Synthetic biologists manipulated these communications, creating cells that respond to new signals or respond in new ways.

In a study carried out over the summer, a group of volunteers drank a white, peppermint-ish concoction laced with billions of bacteria. The microbes had been engineered to break down a naturally occurring toxin in the blood. The vast majority of us can do this without any help. But for those who cannot, these microbes may someday become a living medicine. The trial marks an important milestone in a promising scientific field known as synthetic biology. Two decades ago, researchers started to tinker with living things the way engineers tinker with electronics. They took advantage of the fact that genes typically don’t work in isolation. Instead, many genes work together, activating and deactivating one another. Synthetic biologists manipulated these communications, creating cells that respond to new signals or respond in new ways. The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car.

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car. I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”

I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”