Theodore P. Hill in Quillette:

In the highly controversial area of human intelligence, the ‘Greater Male Variability Hypothesis’ (GMVH) asserts that there are more idiots and more geniuses among men than among women. Darwin’s research on evolution in the nineteenth century found that, although there are many exceptions for specific traits and species, there is generally more variability in males than in females of the same species throughout the animal kingdom.

In the highly controversial area of human intelligence, the ‘Greater Male Variability Hypothesis’ (GMVH) asserts that there are more idiots and more geniuses among men than among women. Darwin’s research on evolution in the nineteenth century found that, although there are many exceptions for specific traits and species, there is generally more variability in males than in females of the same species throughout the animal kingdom.

Evidence for this hypothesis is fairly robust and has been reported in species ranging from adders and sockeye salmon to wasps and orangutans, as well as humans. Multiple studies have found that boys and men are over-represented at both the high and low ends of the distributions in categories ranging from birth weight and brain structures and 60-meter dash times to reading and mathematics test scores. There are significantly more men than women, for example, among Nobel laureates, music composers, and chess champions—and also among homeless people, suicide victims, and federal prison inmates.

Darwin had also raised the question of why males in many species might have evolved to be more variable than females, and when I learned that the answer to his question remained elusive, I set out to look for a scientific explanation.

More here. And here is a rebuttal by the Fields Medalist Sir Tim Gowers writing in his own blog:

I was disturbed recently by reading about an incident in which a paper was accepted by the Mathematical Intelligencer and then rejected, after which it was accepted and published online by the New York Journal of Mathematics, where it lasted for three days before disappearing and being replaced by another paper of the same length. The reason for this bizarre sequence of events? The paper concerned the “variability hypothesis”, the idea, apparently backed up by a lot of evidence, that there is a strong tendency for traits that can be measured on a numerical scale to show more variability amongst males than amongst females. I do not know anything about the quality of this evidence, other than that there are many papers that claim to observe greater variation amongst males of one trait or another, so that if you want to make a claim along the lines of “you typically see more males both at the top and the bottom of the scale” then you can back it up with a long list of citations.

I was disturbed recently by reading about an incident in which a paper was accepted by the Mathematical Intelligencer and then rejected, after which it was accepted and published online by the New York Journal of Mathematics, where it lasted for three days before disappearing and being replaced by another paper of the same length. The reason for this bizarre sequence of events? The paper concerned the “variability hypothesis”, the idea, apparently backed up by a lot of evidence, that there is a strong tendency for traits that can be measured on a numerical scale to show more variability amongst males than amongst females. I do not know anything about the quality of this evidence, other than that there are many papers that claim to observe greater variation amongst males of one trait or another, so that if you want to make a claim along the lines of “you typically see more males both at the top and the bottom of the scale” then you can back it up with a long list of citations.

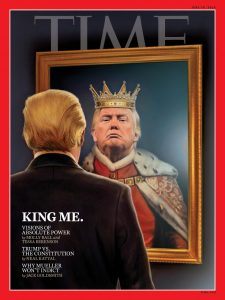

You can see, or probably already know, where this is going: some people like to claim that the reason that women are underrepresented at the top of many fields is simply that the top (and bottom) people, for biological reasons, tend to be male. There is a whole narrative, much loved by many on the political right, that says that this is an uncomfortable truth that liberals find so difficult to accept that they will do anything to suppress it. There is also a counter-narrative that says that people on the far right keep on trying to push discredited claims about the genetic basis for intelligence, differences amongst various groups, and so on, in order to claim that disadvantaged groups are innately disadvantaged rather than disadvantaged by external circumstances.

I myself, as will be obvious, incline towards the liberal side, but I also care about scientific integrity, so I felt I couldn’t just assume that the paper in question had been rightly suppressed.

More here.

For something of such obvious importance, money is kind of mysterious. It can, as Homer Simpson once memorably noted, be exchanged for goods and services. But who decides exactly how many goods/services a given unit of money can buy? And what maintains the social contract that we all agree to go along with it? Technology is changing what money is and how we use it, and Neha Narula is a leader in thinking about where money is going. One much-hyped aspect is the advent of blockchain technology, which has led to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. We talk about what the blockchain really is, how it enables new kinds of currency, and from a wider perspective whether it can help restore a more individualistic, decentralized Web.

For something of such obvious importance, money is kind of mysterious. It can, as Homer Simpson once memorably noted, be exchanged for goods and services. But who decides exactly how many goods/services a given unit of money can buy? And what maintains the social contract that we all agree to go along with it? Technology is changing what money is and how we use it, and Neha Narula is a leader in thinking about where money is going. One much-hyped aspect is the advent of blockchain technology, which has led to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. We talk about what the blockchain really is, how it enables new kinds of currency, and from a wider perspective whether it can help restore a more individualistic, decentralized Web. In halls and moods of violent possession, we speak of languages as things we “have.” This mood comes easy when the books are small and green—a Loeb’s fits in the palm like a secret jewel, a perfect bun. Its loose-woven ribbon reminds us the gift is inside, our reading an unwrapping—happy birthday to our most serious, our highest mind. In the early aughts, I was often high haha.

In halls and moods of violent possession, we speak of languages as things we “have.” This mood comes easy when the books are small and green—a Loeb’s fits in the palm like a secret jewel, a perfect bun. Its loose-woven ribbon reminds us the gift is inside, our reading an unwrapping—happy birthday to our most serious, our highest mind. In the early aughts, I was often high haha. GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, Mozambique — We are flying in a Bat Hawk aircraft — which may be named for a raptor that preys on bats but looks more like a giant, lime-green dragonfly — and my hair, thanks to the open cockpit, has gone full Phyllis Diller. Scudding above flood plains the color of worn pool table felt and mud flats split like jigsaw puzzles, we dip toward the treetops and see herds of waterbuck scatter with an impatient flash of their bull’s-eye rumps. We are searching for the elusive tuskless elephants of Gorongosa, elephants that naturally lack the magnificent ivory staffs all too tragically coveted by wealthy collectors worldwide. Tuskless elephants

GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, Mozambique — We are flying in a Bat Hawk aircraft — which may be named for a raptor that preys on bats but looks more like a giant, lime-green dragonfly — and my hair, thanks to the open cockpit, has gone full Phyllis Diller. Scudding above flood plains the color of worn pool table felt and mud flats split like jigsaw puzzles, we dip toward the treetops and see herds of waterbuck scatter with an impatient flash of their bull’s-eye rumps. We are searching for the elusive tuskless elephants of Gorongosa, elephants that naturally lack the magnificent ivory staffs all too tragically coveted by wealthy collectors worldwide. Tuskless elephants

Little Miracles 2:

Little Miracles 2:

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

It must be hard for

It must be hard for  In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.”

In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.” As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment.

As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment.