Christy Wampole in Aeon:

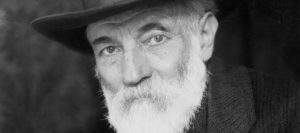

Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate.

Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate.

As a Christian convert who criticised the Catholic Church and as a communist sympathiser who denounced Stalinism and confronted Trotsky over hazardous party developments, Weil’s independence of mind and resistance to ideological conformity are central to her philosophy. In addition to her intelligence, other aspects of her biography have captured the public’s imagination. As a child during the First World War, she refused sugar because soldiers on the front could have none. Diagnosed with tuberculosis, she died at 34 when working for the resistance government France libre in London, refusing to eat more than the citizens’ rations of her German-occupied France. Teachers and classmates called her the Martian and the Red Virgin, nicknames suggestive of her strangeness and asexuality. A philosopher who refused to cloister herself behind academia’s walls, she worked in factories and vineyards, and left France during the Spanish Civil War to fight alongside the Durruti Column anarchists, a failed mission in many respects.

Several mystical experiences, including Weil’s discovery of the poem ‘Love (III)’ by the 17th-century poet George Herbert led her to embrace Christianity, and many have called for her canonisation as a saint. In her book Devotion (2017), the Francophile poet and punk-rock star Patti Smith described Weil as ‘an admirable model for a multitude of mindsets. Brilliant and privileged, she coursed through the great halls of higher learning, forfeiting all to embark on a difficult path of revolution, revelation, public service, and sacrifice.’ The French politician Charles de Gaulle thought Weil was mad, while the authors Albert Camus, André Gide and T S Eliot recognised her as one of the greatest minds of her time.

More here.

The killing of other human beings in war makes graphic an abiding moral dilemma: You might try to make an evil less outrageous, or you might try to get rid of it altogether—but it is not clear that it is possible to do both at the same time. In one of her Twenty-One Love Poems, Adrienne Rich imagines imposing controls on the use of force until it all but disappears: “Such hands might carry out an unavoidable violence / with such restraint,” she writes, “with such a grasp / of the range and limits of violence / that violence ever after would be obsolete.” Yet the lines contradict themselves: If violence is inevitable, however contained or humane, it is not gone.

The killing of other human beings in war makes graphic an abiding moral dilemma: You might try to make an evil less outrageous, or you might try to get rid of it altogether—but it is not clear that it is possible to do both at the same time. In one of her Twenty-One Love Poems, Adrienne Rich imagines imposing controls on the use of force until it all but disappears: “Such hands might carry out an unavoidable violence / with such restraint,” she writes, “with such a grasp / of the range and limits of violence / that violence ever after would be obsolete.” Yet the lines contradict themselves: If violence is inevitable, however contained or humane, it is not gone.

In a recent speech at the United Nations, President Trump

In a recent speech at the United Nations, President Trump  All women become like their mothers,” says Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest. “That is their tragedy. No man does, and that is his.” Left hanging there, of course, is the implication that the son’s tragedy is that he becomes like his father instead. In Oscar Wilde’s own case, that might not have been such a terrible thing, at least for his creative productivity. Colm Tóibín’s sparkling little book on Sir William Wilde, WB Yeats’s father John and James Joyce’s father John Stanislaus, seems originally to have been called “Prodigal Fathers” – the phantom title appears on the inside flap of the cover. It may have been dropped because of Sir William, for whom the word – with its implications of wasted talent – is a poor fit. But it certainly works for John Butler Yeats and John Stanislaus Joyce. And yet the joy of Tóibín’s erudite, subtle, witty and often deeply moving biographical essays is that one generation’s paternal prodigality can become the next generation’s powerhouse of neurotic energy.

All women become like their mothers,” says Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest. “That is their tragedy. No man does, and that is his.” Left hanging there, of course, is the implication that the son’s tragedy is that he becomes like his father instead. In Oscar Wilde’s own case, that might not have been such a terrible thing, at least for his creative productivity. Colm Tóibín’s sparkling little book on Sir William Wilde, WB Yeats’s father John and James Joyce’s father John Stanislaus, seems originally to have been called “Prodigal Fathers” – the phantom title appears on the inside flap of the cover. It may have been dropped because of Sir William, for whom the word – with its implications of wasted talent – is a poor fit. But it certainly works for John Butler Yeats and John Stanislaus Joyce. And yet the joy of Tóibín’s erudite, subtle, witty and often deeply moving biographical essays is that one generation’s paternal prodigality can become the next generation’s powerhouse of neurotic energy. This year’s broiling summer made us Brits climate-change enthusiasts and environmental doom-mongers in quick succession. First came delight at the disappearance of the traditional rhythms of the English summer. Barbecues no longer sputtered out with the advent of a tensely awaited shower. Sogginess, the traditional texture of the British family trying to enjoy itself outdoors, dried out. Tedium followed, as the parks, which at the start of the season had seemed so welcoming, began to resemble a desolate dustbowl from “The Grapes of Wrath”. And then came despair. It wasn’t the days that were so bad. Most offices have serviceable air-conditioning. But the nights were stagnant, breezeless hellscapes as British homes, whose cavity walls had been obediently filled with mineral fibre and formaldehyde foam to retain every last whisper of heat during the winter, turned into bakeries. Sleep evaporated along with everything else and the simplest tasks became cryptic. I stood in front of my front door flummoxed when faced with two locks that need opening with different keys. Anxiety levels rose and tempers frayed.

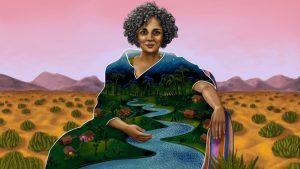

This year’s broiling summer made us Brits climate-change enthusiasts and environmental doom-mongers in quick succession. First came delight at the disappearance of the traditional rhythms of the English summer. Barbecues no longer sputtered out with the advent of a tensely awaited shower. Sogginess, the traditional texture of the British family trying to enjoy itself outdoors, dried out. Tedium followed, as the parks, which at the start of the season had seemed so welcoming, began to resemble a desolate dustbowl from “The Grapes of Wrath”. And then came despair. It wasn’t the days that were so bad. Most offices have serviceable air-conditioning. But the nights were stagnant, breezeless hellscapes as British homes, whose cavity walls had been obediently filled with mineral fibre and formaldehyde foam to retain every last whisper of heat during the winter, turned into bakeries. Sleep evaporated along with everything else and the simplest tasks became cryptic. I stood in front of my front door flummoxed when faced with two locks that need opening with different keys. Anxiety levels rose and tempers frayed. I was an only child raised by a divorced, working, well-educated, secularist, Westernised mother and an uneducated, spiritual, Eastern grandmother. Born in France, I moved to Turkey with my mother when my parents’ marriage came to an end. Although I was small when I left Strasbourg, I often think about our little flat and remember it as a place full of French, Italian, Turkish, Algerian, Lebanese leftist students who passionately discussed the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, read poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky and collectively dreamt about the Revolution. From there I was zoomed to my Grandma’s neighbourhood in Ankara – a very patriarchal and very conservative-Muslim environment. Back then, in the late 1970s, there was increasing political violence and turmoil in Turkey. Every day a bomb exploded somewhere, people got killed on the streets, there were shootings on university campuses. But inside Grandma’s house what prevailed were superstitions, evil eye beads, coffee cup readings and the oral culture of the Middle East. In all my novels there has been a continuous interest in both: the world of stories, magic and mysticism inside the house, and the world of politics, conflict, inequality and discrimination outside the window.

I was an only child raised by a divorced, working, well-educated, secularist, Westernised mother and an uneducated, spiritual, Eastern grandmother. Born in France, I moved to Turkey with my mother when my parents’ marriage came to an end. Although I was small when I left Strasbourg, I often think about our little flat and remember it as a place full of French, Italian, Turkish, Algerian, Lebanese leftist students who passionately discussed the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, read poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky and collectively dreamt about the Revolution. From there I was zoomed to my Grandma’s neighbourhood in Ankara – a very patriarchal and very conservative-Muslim environment. Back then, in the late 1970s, there was increasing political violence and turmoil in Turkey. Every day a bomb exploded somewhere, people got killed on the streets, there were shootings on university campuses. But inside Grandma’s house what prevailed were superstitions, evil eye beads, coffee cup readings and the oral culture of the Middle East. In all my novels there has been a continuous interest in both: the world of stories, magic and mysticism inside the house, and the world of politics, conflict, inequality and discrimination outside the window. Mohammed Hanif’s critically acclaimed, Booker Prize-longlisted debut novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes managed to be both a riotous thriller and a merciless political satire. Running like a red thread through its cat’s-cradle makeup of plot arcs and narrative tangents, key exploits and attendant conspiracy theories, was one main strand concerning the mysterious plane crash that killed Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq.

Mohammed Hanif’s critically acclaimed, Booker Prize-longlisted debut novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes managed to be both a riotous thriller and a merciless political satire. Running like a red thread through its cat’s-cradle makeup of plot arcs and narrative tangents, key exploits and attendant conspiracy theories, was one main strand concerning the mysterious plane crash that killed Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq. In 2007, The New York Times published an op-ed titled “

In 2007, The New York Times published an op-ed titled “ On February 2, 2003, the political scientist John J. Mearsheimer published a co-authored op-ed in The New York Times that lambasted the Bush Administration’s case for invading Iraq. In a carefully laid out argument, Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, a fellow scholar of international relations, predicted that deposing Saddam Hussein would cause more problems than it solved. They argued that the dictator needed to be contained, and that preventative war was not just unnecessary, but harmful.

On February 2, 2003, the political scientist John J. Mearsheimer published a co-authored op-ed in The New York Times that lambasted the Bush Administration’s case for invading Iraq. In a carefully laid out argument, Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, a fellow scholar of international relations, predicted that deposing Saddam Hussein would cause more problems than it solved. They argued that the dictator needed to be contained, and that preventative war was not just unnecessary, but harmful. First-time visitors to India are often struck by the abrupt contrasts in the built environment. A realm of older, urban-fabric chaos—one that works extremely well in the manner that pedestrian-oriented cities do anywhere—will suddenly give way to a realm of more recent dysfunctional sprawl. Traditional urban forms in India show an adaptive response to climate and to centuries of patterns of use. But the country’s newer, road-emphasizing development applies 20th-century models of Western planning—models that we in the West have ourselves come to lament. Such urban growth patterns have unintended, undesirable consequences even in places where nearly everyone can afford a car; they can be disastrous in places like India where many people cannot. And it’s not just the road patterns that are ill suited to the country’s needs. Disregard for local circumstances also characterizes much 20th-century Indian architecture—resulting in climate-controlled structures indistinguishable in style from buildings you might see in the United States, Scandinavia, China, or Africa.Realigning contemporary design and architecture to the needs of India has been a major theme in the life’s work of B.V. Doshi. He is the winner of this year’s Pritzker Prize, often described as the Nobel Prize of architecture. It is invariably awarded to architects of great talent, most of whom are very well known. The Pritzker family fortune that funds the award was derived in large part from the Hyatt hotel chain, and the honorees tend to be the sort of starchitects whose name recognition resembles that of the chain—and whose commissions are about as widespread as its locations. Most require a map of several continents, if not the full world, to encompass their work.

First-time visitors to India are often struck by the abrupt contrasts in the built environment. A realm of older, urban-fabric chaos—one that works extremely well in the manner that pedestrian-oriented cities do anywhere—will suddenly give way to a realm of more recent dysfunctional sprawl. Traditional urban forms in India show an adaptive response to climate and to centuries of patterns of use. But the country’s newer, road-emphasizing development applies 20th-century models of Western planning—models that we in the West have ourselves come to lament. Such urban growth patterns have unintended, undesirable consequences even in places where nearly everyone can afford a car; they can be disastrous in places like India where many people cannot. And it’s not just the road patterns that are ill suited to the country’s needs. Disregard for local circumstances also characterizes much 20th-century Indian architecture—resulting in climate-controlled structures indistinguishable in style from buildings you might see in the United States, Scandinavia, China, or Africa.Realigning contemporary design and architecture to the needs of India has been a major theme in the life’s work of B.V. Doshi. He is the winner of this year’s Pritzker Prize, often described as the Nobel Prize of architecture. It is invariably awarded to architects of great talent, most of whom are very well known. The Pritzker family fortune that funds the award was derived in large part from the Hyatt hotel chain, and the honorees tend to be the sort of starchitects whose name recognition resembles that of the chain—and whose commissions are about as widespread as its locations. Most require a map of several continents, if not the full world, to encompass their work. On the night

On the night  The Genizah is a trove of Hebrew documents that were found largely intact in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo. For many reasons, the more celebrated part of the Genizah among contemporary scholars is what we could term its “literary” component: old Hebrew books of many kinds, scrolls and codices, with writings both sacred and secular. Throughout the 20th century, scholars were excited to publish new works of ancient rabbis for instance, or for the first time, their opponents from the first century BCE or the 9th century CE. But the Genizah did not only include literary materials, it was the repository for anything with Hebrew lettering in medieval Fustāt. Letters and legal documents abound. Scholastic interest in this “documentary” Genizah took some time to mature, but its cataloguing and scrutiny in recent decades has yielded a wealth of fine-grained information that medievalists specializing in other geographic areas can only dream of.

The Genizah is a trove of Hebrew documents that were found largely intact in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo. For many reasons, the more celebrated part of the Genizah among contemporary scholars is what we could term its “literary” component: old Hebrew books of many kinds, scrolls and codices, with writings both sacred and secular. Throughout the 20th century, scholars were excited to publish new works of ancient rabbis for instance, or for the first time, their opponents from the first century BCE or the 9th century CE. But the Genizah did not only include literary materials, it was the repository for anything with Hebrew lettering in medieval Fustāt. Letters and legal documents abound. Scholastic interest in this “documentary” Genizah took some time to mature, but its cataloguing and scrutiny in recent decades has yielded a wealth of fine-grained information that medievalists specializing in other geographic areas can only dream of. When I suggest a nexus between style and morality I mean always to keep the query centered on the book, to interrogate the book’s moral vision as it is activated in language. That vision, like everything else in the writer’s arsenal, is manifest in style. Language is our fullest, most accurate embodiment of mind. How you write is how you think, and there’s reciprocity there, a fertile feedback loop, because the writing in turn sharpens the thinking, which in turn sharpens the writing. This is what Goethe means by “a writer’s style is a true reflection of his inner life.” Remember, too, Nabokov’s oft-cited line: “Style is matter.” He means that style is not something gummed onto prose after the fact—style is the fact. Style is born of subject. Robert Penn Warren makes a similar observation: “The style of a writer represents his stance toward experience.” That’s what Auden means in his second consideration above.

When I suggest a nexus between style and morality I mean always to keep the query centered on the book, to interrogate the book’s moral vision as it is activated in language. That vision, like everything else in the writer’s arsenal, is manifest in style. Language is our fullest, most accurate embodiment of mind. How you write is how you think, and there’s reciprocity there, a fertile feedback loop, because the writing in turn sharpens the thinking, which in turn sharpens the writing. This is what Goethe means by “a writer’s style is a true reflection of his inner life.” Remember, too, Nabokov’s oft-cited line: “Style is matter.” He means that style is not something gummed onto prose after the fact—style is the fact. Style is born of subject. Robert Penn Warren makes a similar observation: “The style of a writer represents his stance toward experience.” That’s what Auden means in his second consideration above. The French people are constantly hauled on to a Corneille-like stage with and by de Gaulle, two characters in search of a destiny, with soliloquies, debates, monologues, conducted in newspapers, radio and television although, such is the nature of a biography, “the people” are really the audience that listens and is moulded, enchanted or aroused to sublimity by the suasion of that resonant, nasal, rhythmic voice. As was noticed on several occasions, de Gaulle was a traditional Catholic Christian; he rarely spoke of or even mentioned God but rarely failed to speak instead of France, the great stained-glass rose window in which the divine light had glowed through the centuries in radiance or in sombre melancholy, picking out at irregular intervals the ranged silhouettes of a Clovis, a Charlemagne, an Henri IV, a Joan of Arc, Louis XI, a Colbert, Richelieu, Louis XIV (or his great general Louvois), a Napoleon and, at last, a de Gaulle. Régis Debray in 1990 is quoted: “In my dreams I am on terms of easy familiarity with Louis XI, with Lenin, with Edison and Lincoln. But I quail before de Gaulle. He is the Great Other, the inaccessible absolute … Napoleon was the great political myth of the nineteenth century; de Gaulle of the twentieth. The sublime, it seems, appears in France only once a century.” Debray had once regarded Mitterrand as a saviour ‑ rather hard to believe now in any retrospective light ‑ but this literary-political canonisation would have pleased de Gaulle, for he certainly believed it to be true, true as only a myth can be.

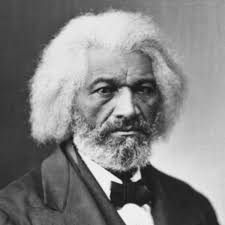

The French people are constantly hauled on to a Corneille-like stage with and by de Gaulle, two characters in search of a destiny, with soliloquies, debates, monologues, conducted in newspapers, radio and television although, such is the nature of a biography, “the people” are really the audience that listens and is moulded, enchanted or aroused to sublimity by the suasion of that resonant, nasal, rhythmic voice. As was noticed on several occasions, de Gaulle was a traditional Catholic Christian; he rarely spoke of or even mentioned God but rarely failed to speak instead of France, the great stained-glass rose window in which the divine light had glowed through the centuries in radiance or in sombre melancholy, picking out at irregular intervals the ranged silhouettes of a Clovis, a Charlemagne, an Henri IV, a Joan of Arc, Louis XI, a Colbert, Richelieu, Louis XIV (or his great general Louvois), a Napoleon and, at last, a de Gaulle. Régis Debray in 1990 is quoted: “In my dreams I am on terms of easy familiarity with Louis XI, with Lenin, with Edison and Lincoln. But I quail before de Gaulle. He is the Great Other, the inaccessible absolute … Napoleon was the great political myth of the nineteenth century; de Gaulle of the twentieth. The sublime, it seems, appears in France only once a century.” Debray had once regarded Mitterrand as a saviour ‑ rather hard to believe now in any retrospective light ‑ but this literary-political canonisation would have pleased de Gaulle, for he certainly believed it to be true, true as only a myth can be. Douglass’s current status as a national hero poses a challenge for the biographer, making it difficult to view him dispassionately. Moreover, those who seek to tell his story must compete with their subject’s own version of it. Douglass published three autobiographies, among the greatest works of this genre in American literature. They present not only a powerful indictment of slavery, but also a tale of extraordinary individual achievement (it is no accident that Douglass’s most frequently delivered lecture was titled “Self-Made Men”). Like all autobiographies, however, Douglass’s were simultaneously historical narratives and works of the imagination. As David Blight notes in his new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, some passages in them—especially those relating to Douglass’s childhood—are “almost pure invention,” which means the biographer must resist the temptation to take these books entirely at face value.

Douglass’s current status as a national hero poses a challenge for the biographer, making it difficult to view him dispassionately. Moreover, those who seek to tell his story must compete with their subject’s own version of it. Douglass published three autobiographies, among the greatest works of this genre in American literature. They present not only a powerful indictment of slavery, but also a tale of extraordinary individual achievement (it is no accident that Douglass’s most frequently delivered lecture was titled “Self-Made Men”). Like all autobiographies, however, Douglass’s were simultaneously historical narratives and works of the imagination. As David Blight notes in his new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, some passages in them—especially those relating to Douglass’s childhood—are “almost pure invention,” which means the biographer must resist the temptation to take these books entirely at face value. The cultural association between women and the manufacture of textiles runs deep. Many of the deities associated with spinning and weaving are female: Neith in pre-Dynastic Egypt; Grecian Athena; the Norse goddess Frigg and the Chinese Silkworm Goddess. Skill with needle, thread or a loom was seen in many cultures as an intrinsic part of a woman’s value. In Greece, the birth of a baby girl was sometimes marked by placing a tuft of wool by the door of a home. And Homer wrote that when his countrymen raided towns and villages they killed the men they encountered, but women were spared in order to spin and weave in captivity. The “distaff side” was a traditional English term for the maternal side of a family. Women the world over were buried with spindles and distaffs, the very tools they wielded so dexterously and for so many hours in life. Sarah Arderne, a member of the lesser gentry in northern England in the late eighteenth century, bought muslin for her husband’s cravats and handkerchief and supervised the laundering of all his linens. She was pretty typical: it wasn’t unusual for men of this class and period to live and die without ever taking responsibility for their own shirts.

The cultural association between women and the manufacture of textiles runs deep. Many of the deities associated with spinning and weaving are female: Neith in pre-Dynastic Egypt; Grecian Athena; the Norse goddess Frigg and the Chinese Silkworm Goddess. Skill with needle, thread or a loom was seen in many cultures as an intrinsic part of a woman’s value. In Greece, the birth of a baby girl was sometimes marked by placing a tuft of wool by the door of a home. And Homer wrote that when his countrymen raided towns and villages they killed the men they encountered, but women were spared in order to spin and weave in captivity. The “distaff side” was a traditional English term for the maternal side of a family. Women the world over were buried with spindles and distaffs, the very tools they wielded so dexterously and for so many hours in life. Sarah Arderne, a member of the lesser gentry in northern England in the late eighteenth century, bought muslin for her husband’s cravats and handkerchief and supervised the laundering of all his linens. She was pretty typical: it wasn’t unusual for men of this class and period to live and die without ever taking responsibility for their own shirts. Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate.

Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate. When something in the body goes wrong, we see a doctor, get examined, get swabbed or draw blood, and usually leave with an answer. But for many patients and families, medical examination doesn’t lead to a diagnosis—and what do they do then? A paper

When something in the body goes wrong, we see a doctor, get examined, get swabbed or draw blood, and usually leave with an answer. But for many patients and families, medical examination doesn’t lead to a diagnosis—and what do they do then? A paper