Betsy Sinclair at The Conversation:

Political scientists Steven Webster, Elizabeth Connors and I have investigated what happens to people’s social networks – their friends, family and neighbors – when partisan anger takes over. For example, suppose your neighbor is a member of the opposite political party. You’ve always watered their plants when they go on vacation. Given the news these days and how angry you’re feeling, what will you say when they ask for help during their next trip?

Political scientists Steven Webster, Elizabeth Connors and I have investigated what happens to people’s social networks – their friends, family and neighbors – when partisan anger takes over. For example, suppose your neighbor is a member of the opposite political party. You’ve always watered their plants when they go on vacation. Given the news these days and how angry you’re feeling, what will you say when they ask for help during their next trip?

We found that when someone is angry with the opposite party, they avoid people with those views. That can include not assisting neighbors with various tasks, avoiding social gatherings attended by people from the other side, and refusing to date people who vote differently. It means being disappointed if your son or daughter marries a supporter of the opposing party, and even severing close friendships or distancing yourself from close relatives.

We see that political anger disrupts ordinary life – coffee with a friend – as well as more major life decisions. Political anger breaks our social networks.

People rely on their relationships to understand our world – and to vote. The more we isolate ourselves from people who see things differently, the easier it is to misunderstand them, pushing us to separate even more.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

S

S Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read. Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania.

Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania. Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have.

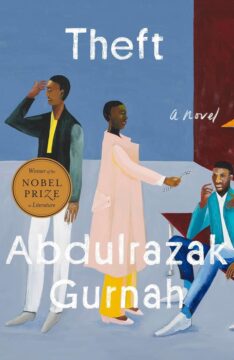

Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have. “Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England.

“Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England. Masaki Kashiwara, a Japanese mathematician, received this year’s Abel Prize, which aspires to be the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in math. Dr. Kashiwara’s highly abstract work combined algebra, geometry and differential equations in surprising ways.

Masaki Kashiwara, a Japanese mathematician, received this year’s Abel Prize, which aspires to be the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in math. Dr. Kashiwara’s highly abstract work combined algebra, geometry and differential equations in surprising ways. I

I I

I What happened to former Columbia University student and Palestine rights activist Mahmoud Khalil has rightly alarmed many indignant Americans. Some have sought reassurance in the idea that since his abduction is nakedly unconstitutional, the institutions of American democracy—the Constitution, rule of law, brakes on the unchecked use of power—will swoop in to put an end to the madness. After all, we have the vaunted First Amendment. Attorneys from the ACLU and Center for Constitutional Rights are representing Khalil; surely their free speech arguments will impel his freedom and cancel his deportation. His detention surely is just one more instance of Trumpian insanity. Surely it will prove legally frivolous.

What happened to former Columbia University student and Palestine rights activist Mahmoud Khalil has rightly alarmed many indignant Americans. Some have sought reassurance in the idea that since his abduction is nakedly unconstitutional, the institutions of American democracy—the Constitution, rule of law, brakes on the unchecked use of power—will swoop in to put an end to the madness. After all, we have the vaunted First Amendment. Attorneys from the ACLU and Center for Constitutional Rights are representing Khalil; surely their free speech arguments will impel his freedom and cancel his deportation. His detention surely is just one more instance of Trumpian insanity. Surely it will prove legally frivolous. Short though her life was, O’Connor produced a distinctive body of work—two short-story collections, A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Everything that Rises Must Converge, and her two novels Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away, along with luminous essays and a rich, often hilariously detailed, correspondence—that more than justifies her standing as a classic American author. Her fiction is replete with certain types—hillbillies and carnival barkers, tent revival preachers and geek show performers—but her concern was always with grace, of the ways in which the irredeemable can be redeemed, the unsalvageable can be saved (which is to say all of us to varying degrees). What fascinated O’Connor, intellectually and spiritually, were the complexities of the soul, not how good people can be capable of bad, but how even evil people are sometimes capable of good, the ways in which “this current comes openly to the surface and is seen as the sudden emergence of the underground rivers of the mind into the clear spring of grace,” as she wrote in a 1956 book review. A moral universe with original sin, yes, but not total depravity.

Short though her life was, O’Connor produced a distinctive body of work—two short-story collections, A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Everything that Rises Must Converge, and her two novels Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away, along with luminous essays and a rich, often hilariously detailed, correspondence—that more than justifies her standing as a classic American author. Her fiction is replete with certain types—hillbillies and carnival barkers, tent revival preachers and geek show performers—but her concern was always with grace, of the ways in which the irredeemable can be redeemed, the unsalvageable can be saved (which is to say all of us to varying degrees). What fascinated O’Connor, intellectually and spiritually, were the complexities of the soul, not how good people can be capable of bad, but how even evil people are sometimes capable of good, the ways in which “this current comes openly to the surface and is seen as the sudden emergence of the underground rivers of the mind into the clear spring of grace,” as she wrote in a 1956 book review. A moral universe with original sin, yes, but not total depravity.  Anyone who takes on Hegel knows they have their work cut out. He is among the most complex, capacious and ambitious philosophers in the history of Western thought. And unlike other comparable figures in that tradition, such as Plato, Descartes or Hume, his style of writing can be notoriously difficult – indeed one of the more striking aspects of the book is the contrast between Bourke’s consistently clear, exact and clipped style and the frequently obscure, vague and stentorian prose of his subject. As the title of Bourke’s book signals, it is not a synoptic or comprehensive study of Hegel’s thought. Rather it is primarily concerned with the historicism and political philosophy of the nineteenth century thinker and even then in a quite defined way.

Anyone who takes on Hegel knows they have their work cut out. He is among the most complex, capacious and ambitious philosophers in the history of Western thought. And unlike other comparable figures in that tradition, such as Plato, Descartes or Hume, his style of writing can be notoriously difficult – indeed one of the more striking aspects of the book is the contrast between Bourke’s consistently clear, exact and clipped style and the frequently obscure, vague and stentorian prose of his subject. As the title of Bourke’s book signals, it is not a synoptic or comprehensive study of Hegel’s thought. Rather it is primarily concerned with the historicism and political philosophy of the nineteenth century thinker and even then in a quite defined way. Hunter gatherers were not non-violent noble savages by any stretch of the imagination. They were relatively violent when compared with modern standards and even when compared with rates of violence experienced by other primates and mammals in general. However, we think this is primarily because human conflict is so lethal, not because it happens so often. On the contrary, hunter gatherers typically exhibit non-violent norms, with amoral and atypical sociopaths accounting for a disproportionate share of violence, just as in our own societies today.

Hunter gatherers were not non-violent noble savages by any stretch of the imagination. They were relatively violent when compared with modern standards and even when compared with rates of violence experienced by other primates and mammals in general. However, we think this is primarily because human conflict is so lethal, not because it happens so often. On the contrary, hunter gatherers typically exhibit non-violent norms, with amoral and atypical sociopaths accounting for a disproportionate share of violence, just as in our own societies today. Consciousness is easier to possess than to define. One thing we can do is to look into the brain and see what lights up when conscious awareness is taking place. A complete understanding of this would be known as the “neural correlates of consciousness.” Once we have that, we could hopefully make progress on developing a theoretical picture of what consciousness is and why it happens. Today’s guest, Christof Koch, is a leader in the search for neural correlates and an advocate of a particular approach to consciousness,

Consciousness is easier to possess than to define. One thing we can do is to look into the brain and see what lights up when conscious awareness is taking place. A complete understanding of this would be known as the “neural correlates of consciousness.” Once we have that, we could hopefully make progress on developing a theoretical picture of what consciousness is and why it happens. Today’s guest, Christof Koch, is a leader in the search for neural correlates and an advocate of a particular approach to consciousness,