by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East.

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East.

While silk has always been a coveted item, a symbol of wealth and power for millennia in many cultures around the world, the detailed, de-mythologized, accurate history of what we have come to know as the “Silk Road” is not only of little interest but has been deliberately suppressed in the West. Besides a vague connection with Marco Polo, most people usually draw a blank at its mention. During the many years that I have been working on (and presenting from) a trilogy of poetry manuscripts based on aspects of this history, I have come across few readers (including writers and academics) in the US who have a clear idea of the regions that have been, since antiquity, a part of these trade routes we call the Silk Road (or “’Seidenstrasse,” a term coined by the German historian Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877) to define a network of land and sea routes of central and continuous importance to global trade as well as civilizational influences and the shifts in geographical borders around the world: a history that has been shaping not only how the world map looks from time to time, but how attitudes, knowledge, goods, technology, weapons, fashions, and even diseases and cures have been spreading across the continents and through the centuries. Read more »

A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

In Mohammed Hanif’s third novel Red Birds, US Air Force Major Ellie despairs of mission simulations being “dreamt up by some kid who’d never seen the inside of a cockpit”. Readers of literary fiction about war, if not of fiction in general, may feel a similar despair. Does the writer have enough authority to make their simulation convincing? Before Hanif was a Booker-longlisted author, or wrote for the New York Times and BBC, he trained as a pilot in Pakistan’s air force. What Major Ellie says about ejector seats and fireproof suits has the confidence of truth. But much more importantly, Hanif knows about the absurdity of war in a way that a civilian never could.

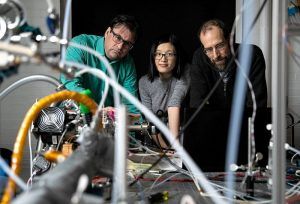

In Mohammed Hanif’s third novel Red Birds, US Air Force Major Ellie despairs of mission simulations being “dreamt up by some kid who’d never seen the inside of a cockpit”. Readers of literary fiction about war, if not of fiction in general, may feel a similar despair. Does the writer have enough authority to make their simulation convincing? Before Hanif was a Booker-longlisted author, or wrote for the New York Times and BBC, he trained as a pilot in Pakistan’s air force. What Major Ellie says about ejector seats and fireproof suits has the confidence of truth. But much more importantly, Hanif knows about the absurdity of war in a way that a civilian never could. Zhen Dai holds up a small glass tube coated with a white powder: calcium carbonate, a ubiquitous compound used in everything from paper and cement to toothpaste and cake mixes. Plop a tablet of it into water, and the result is a fizzy antacid that calms the stomach. The question for Dai, a doctoral candidate at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and her colleagues is whether this innocuous substance could also help humanity to relieve the ultimate case of indigestion: global warming caused by greenhouse-gas pollution.

Zhen Dai holds up a small glass tube coated with a white powder: calcium carbonate, a ubiquitous compound used in everything from paper and cement to toothpaste and cake mixes. Plop a tablet of it into water, and the result is a fizzy antacid that calms the stomach. The question for Dai, a doctoral candidate at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and her colleagues is whether this innocuous substance could also help humanity to relieve the ultimate case of indigestion: global warming caused by greenhouse-gas pollution. In the United States today, the rich lay claim to a higher share of our nation’s wealth than they have at any point since the Gilded Age — and foreign-born residents account for a higher share of our nation’s population than at just about any time since that same era.

In the United States today, the rich lay claim to a higher share of our nation’s wealth than they have at any point since the Gilded Age — and foreign-born residents account for a higher share of our nation’s population than at just about any time since that same era. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 72,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2017, up from some 64,000 the previous year and 52,000 the year before that—a staggering increase with no end in sight. Most involved opioids.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 72,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2017, up from some 64,000 the previous year and 52,000 the year before that—a staggering increase with no end in sight. Most involved opioids. In the beginning, there was smoke. It snaked out of the Andes from the burning leaves of Nicotiana tabacum some 6,000 years ago, spreading across the lands that would come to be known as South America and the Caribbean, until finally reaching the eastern shores of North America. It intermingled with wisps from other plants: kinnickinnick and Datura and passionflower. At first, it meant ceremony. Later, it meant profit. But always the importance of the smoke remained.

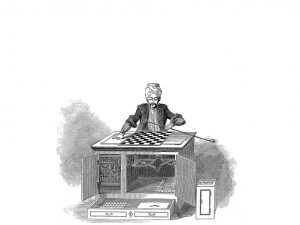

In the beginning, there was smoke. It snaked out of the Andes from the burning leaves of Nicotiana tabacum some 6,000 years ago, spreading across the lands that would come to be known as South America and the Caribbean, until finally reaching the eastern shores of North America. It intermingled with wisps from other plants: kinnickinnick and Datura and passionflower. At first, it meant ceremony. Later, it meant profit. But always the importance of the smoke remained. In 1770 a chess-playing robot, built by a Hungarian inventor, caused a sensation across Europe. It took the form of a life-size wooden figure, dressed in Turkish clothing, seated behind a cabinet which had a chessboard on top. Its clockwork arm could reach out and move pieces on the board. The Mechanical Turk was capable of beating even the best players at chess. Built to amuse the empress Maria Theresa, its fame spread far beyond Vienna, and visitors to her court insisted on seeing it. The Turk toured Europe in the 1780s, prompting much speculation about how it worked, and whether a machine could really think: the Industrial Revolution was just getting started, and many people were questioning to what extent machines could replace people. Nobody ever quite guessed the Turk’s secret. But it eventually transpired that there was a human chess player cleverly concealed in its innards. The apparently intelligent machine depended on a person hidden inside.

In 1770 a chess-playing robot, built by a Hungarian inventor, caused a sensation across Europe. It took the form of a life-size wooden figure, dressed in Turkish clothing, seated behind a cabinet which had a chessboard on top. Its clockwork arm could reach out and move pieces on the board. The Mechanical Turk was capable of beating even the best players at chess. Built to amuse the empress Maria Theresa, its fame spread far beyond Vienna, and visitors to her court insisted on seeing it. The Turk toured Europe in the 1780s, prompting much speculation about how it worked, and whether a machine could really think: the Industrial Revolution was just getting started, and many people were questioning to what extent machines could replace people. Nobody ever quite guessed the Turk’s secret. But it eventually transpired that there was a human chess player cleverly concealed in its innards. The apparently intelligent machine depended on a person hidden inside.

I can’t understand the words. Heck, I can’t even identify all the instruments these guys are playing, but I am loving The HU.

I can’t understand the words. Heck, I can’t even identify all the instruments these guys are playing, but I am loving The HU. Despite Christine Blasey Ford’s stirring testimony, an FBI investigation, thousands of protesters (hundreds of whom were arrested), petitions and phone calls from constituents, an

Despite Christine Blasey Ford’s stirring testimony, an FBI investigation, thousands of protesters (hundreds of whom were arrested), petitions and phone calls from constituents, an  Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing.

Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing. The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have

The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have