William L. Katz in BlackPast.Org:

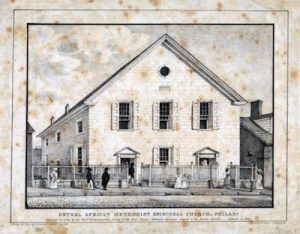

In January 1817 nearly 3,000 African American men met at the Bethel A.M.E. Church (popularly known as Mother Bethel AME) in Philadelphia and denounced the American Colonization Society’s plan to resettle free blacks in West Africa. This gathering was the first black mass protest meeting in the United States. The black leaders who summoned the men to the church endorsed the ACS scheme and fully expected the black men who gathered there to follow their leadership. Instead they rejected the scheme and forced the black leaders to embrace their position.

In January 1817 nearly 3,000 African American men met at the Bethel A.M.E. Church (popularly known as Mother Bethel AME) in Philadelphia and denounced the American Colonization Society’s plan to resettle free blacks in West Africa. This gathering was the first black mass protest meeting in the United States. The black leaders who summoned the men to the church endorsed the ACS scheme and fully expected the black men who gathered there to follow their leadership. Instead they rejected the scheme and forced the black leaders to embrace their position.

The genesis of this remarkable meeting can found in the early efforts of Captain Paul Cuffee, a wealthy black New Bedford ship owner. After an 1811 visit to the British colony of Sierra Leone which had been established to receive free blacks and later recaptives — blacks freed by the British Navy from slaving vessels taking them from Africa to the New World — Cuffee envisioned a similar colony for African Americans somewhere in West Africa. To promote his vision, Cuffee, at great financial loss, brought 38 black volunteer settlers from the United States to Sierra Leone in 1815.

When he returned to the United States with news of the resettlement he persuaded many of the most influential black leaders of the era to support him in transporting larger numbers of African Americans to a yet to be determined colony on the West African coast. Rev. Peter Williams of New York, Rev. Daniel Coker in Baltimore, and James Forten, Bishop Richard Allen, and Rev. Absalom Jones all of Philadelphia, who were the most important African American leaders in the United States at that time, enthusiastically endorsed the plan.

Given the dire situation faced by free blacks in the North during that era, their endorsement was understandable. The vote was denied to all but a handful of black men. No black women could vote at the time. Black workers were limited in the occupations they could pursue and the wages they could receive. In Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and other Northern cities they were subject to attack by white mobs and to the ever present threat of slavecatchers who kidnapped fugitive slaves and on occasion those who had never been enslaved. Thus to many leaders in the “free” North colonization seemed an attractive option.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)