Tyler Malone in Literary Hub:

The sixties were a decade of upheaval and progress, and one of the many areas where that revolutionary spirit reared its head was in the art of nonfiction. In previous decades, nonfiction—particularly if written for periodicals—had been seen mostly as ephemeral reportage. It was for catching up on world events, local matters, and human interest, usually read over a morning cup of coffee, stained with those wet, brown rings. Partially because it was churned out on deadline, factual writing was often pooh-poohed as a lesser art form than fictional writing, with the focus merely on the transfer of information, rather than aesthetic splendor, thematic heft, and formal precision.

The sixties were a decade of upheaval and progress, and one of the many areas where that revolutionary spirit reared its head was in the art of nonfiction. In previous decades, nonfiction—particularly if written for periodicals—had been seen mostly as ephemeral reportage. It was for catching up on world events, local matters, and human interest, usually read over a morning cup of coffee, stained with those wet, brown rings. Partially because it was churned out on deadline, factual writing was often pooh-poohed as a lesser art form than fictional writing, with the focus merely on the transfer of information, rather than aesthetic splendor, thematic heft, and formal precision.

In the sixties, writers like Truman Capote, Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Hunter S. Thompson, and John McPhee changed that perception by imbuing the factual with as much artistry as the fictional. Of course, the “New Journalism,” as it has often been called, might not have been as revolutionary—as new—as our cultural myths imply. McPhee, for his part, thinks this narrative is a bit of hooey.

More here.

It’s hardly news that computers are exerting ever more influence over our lives. And we’re beginning to see the first glimmers of some kind of artificial intelligence: computer programs have become much better than humans at well-defined jobs like playing chess and Go, and are increasingly called upon for messier tasks, like driving cars. Once we leave the highly constrained sphere of artificial games and enter the real world of human actions, our artificial intelligences are going to have to make choices about the best course of action in unclear circumstances: they will have to learn to be ethical. I talk to Derek Leben about what this might mean and what kind of ethics our computers should be taught. It’s a wide-ranging discussion involving computer science, philosophy, economics, and game theory.

It’s hardly news that computers are exerting ever more influence over our lives. And we’re beginning to see the first glimmers of some kind of artificial intelligence: computer programs have become much better than humans at well-defined jobs like playing chess and Go, and are increasingly called upon for messier tasks, like driving cars. Once we leave the highly constrained sphere of artificial games and enter the real world of human actions, our artificial intelligences are going to have to make choices about the best course of action in unclear circumstances: they will have to learn to be ethical. I talk to Derek Leben about what this might mean and what kind of ethics our computers should be taught. It’s a wide-ranging discussion involving computer science, philosophy, economics, and game theory. What makes people susceptible to fake news and other forms of strategic misinformation? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

What makes people susceptible to fake news and other forms of strategic misinformation? And what, if anything, can be done about it? In her new work, artist Dana Schutz takes back her painterly name. Her current canvasses are hyperassertive, full of operatic grandeur, self-mocking turbulence, acidified flooded color, disfigured hideousness, and the psychopathology of her figures — all clawing in some Malthusian struggle for existence. Like this work or not, Schutz is claiming a lot of visual territory for herself. This means more tenacity in the paint, irrepressible surfaces, ambitious scale, and mixed — conflicted — compositional structures.

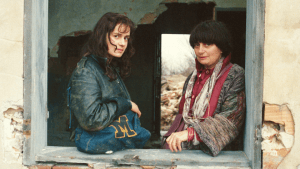

In her new work, artist Dana Schutz takes back her painterly name. Her current canvasses are hyperassertive, full of operatic grandeur, self-mocking turbulence, acidified flooded color, disfigured hideousness, and the psychopathology of her figures — all clawing in some Malthusian struggle for existence. Like this work or not, Schutz is claiming a lot of visual territory for herself. This means more tenacity in the paint, irrepressible surfaces, ambitious scale, and mixed — conflicted — compositional structures. She has been called the Godmother of the New Wave, sometimes the Big Sister, even the Grandmother, but Agnès rides her own wave. She has never slowed down: a ceaseless creative force, she has been on the spot at historic moments. She never puts anything away for good, so old photos turn into films, and whatever she can’t use right away may turn up later in her short films, recycled with fresh invention. On a trip to Germany, the history of 4711 eau de cologne captivates her as much as the venerable cathedral and re-appears in her Agnès de ci de là Varda (Agnes Varda: From Here to There, 2012). She sees the world in a grain of sand—or in a heart-shaped potato. In her garden, she pays as much attention to a tree’s growth as to any honored guest.

She has been called the Godmother of the New Wave, sometimes the Big Sister, even the Grandmother, but Agnès rides her own wave. She has never slowed down: a ceaseless creative force, she has been on the spot at historic moments. She never puts anything away for good, so old photos turn into films, and whatever she can’t use right away may turn up later in her short films, recycled with fresh invention. On a trip to Germany, the history of 4711 eau de cologne captivates her as much as the venerable cathedral and re-appears in her Agnès de ci de là Varda (Agnes Varda: From Here to There, 2012). She sees the world in a grain of sand—or in a heart-shaped potato. In her garden, she pays as much attention to a tree’s growth as to any honored guest. The underlying problem with the advance directives is that they imply the subordination of an irrational human being to their rational former self, essentially splitting a single person into two mutually opposed ones. Many doctors, having watched patients adapt to circumstances they had once expected to find intolerable, doubt whether anyone can accurately predict what they will want after their condition worsens.

The underlying problem with the advance directives is that they imply the subordination of an irrational human being to their rational former self, essentially splitting a single person into two mutually opposed ones. Many doctors, having watched patients adapt to circumstances they had once expected to find intolerable, doubt whether anyone can accurately predict what they will want after their condition worsens. It can be reassuring to reassess life by taking a long view. In this book about “how the Earth made us”,

It can be reassuring to reassess life by taking a long view. In this book about “how the Earth made us”,  Does the language you speak influence how you think? This is the question behind the famous

Does the language you speak influence how you think? This is the question behind the famous  By 2014, many Americans had forgotten about New Atheism. For liberal Americans in the depths of the Bush years, anti-religious best sellers by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens came as—for lack of a better word—a godsend. With the Christian right in the White House, and jihadist terrorism perceived to be a constant danger in the wake of 9/11, a vocal rationalist atheism appeared to many a natural and necessary counterweight. But after nearly six years of Barack Obama’s presidency, Bush and his born-again gang were far from the high seats of power, the War on Terror was no longer a feature of most people’s daily lives, and there was a widespread impression of leftward progress on social issues. The services of the anti-religious crusaders were no longer needed.

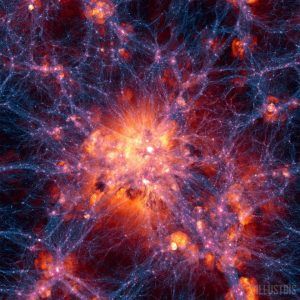

By 2014, many Americans had forgotten about New Atheism. For liberal Americans in the depths of the Bush years, anti-religious best sellers by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens came as—for lack of a better word—a godsend. With the Christian right in the White House, and jihadist terrorism perceived to be a constant danger in the wake of 9/11, a vocal rationalist atheism appeared to many a natural and necessary counterweight. But after nearly six years of Barack Obama’s presidency, Bush and his born-again gang were far from the high seats of power, the War on Terror was no longer a feature of most people’s daily lives, and there was a widespread impression of leftward progress on social issues. The services of the anti-religious crusaders were no longer needed. One of the greatest puzzles in the entire Universe is the dark matter mystery. In theory, for every bit of normal matter (like us) in the Universe, there should be approximately five times as much dark matter. Both normal and dark matter should experience gravitation equally, meaning that the largest structures in the Universe — galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and cosmic filaments — should contain and be dominated by dark matter. When we measure the motions of individual galaxies, both isolated and in clusters, the normal matter alone is not enough to explain what we see. Dark matter is also required.

One of the greatest puzzles in the entire Universe is the dark matter mystery. In theory, for every bit of normal matter (like us) in the Universe, there should be approximately five times as much dark matter. Both normal and dark matter should experience gravitation equally, meaning that the largest structures in the Universe — galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and cosmic filaments — should contain and be dominated by dark matter. When we measure the motions of individual galaxies, both isolated and in clusters, the normal matter alone is not enough to explain what we see. Dark matter is also required. So, there you are, having worked your way through a crowd denser than a Brexit negotiation, standing in front of your prize. The Mona Lisa in the Louvre. What do you do? Look more closely at that enigmatic smile? Wonder at the subtle gradations of light and shadow in Leonardo’s rendering of the face? Admire the illusion of depth?

So, there you are, having worked your way through a crowd denser than a Brexit negotiation, standing in front of your prize. The Mona Lisa in the Louvre. What do you do? Look more closely at that enigmatic smile? Wonder at the subtle gradations of light and shadow in Leonardo’s rendering of the face? Admire the illusion of depth? Sometimes my experiences with the Postal Service are almost enough to turn me into a right-wing libertarian. For instance: They offer a special discounted rate for sending magazines through the post. Which is good—I run a magazine that is sent through the post! In order to get the rate, however, you have to meticulously obey every single instruction in the 56 pages of

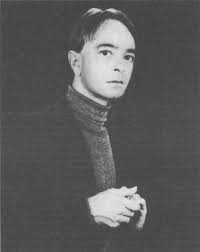

Sometimes my experiences with the Postal Service are almost enough to turn me into a right-wing libertarian. For instance: They offer a special discounted rate for sending magazines through the post. Which is good—I run a magazine that is sent through the post! In order to get the rate, however, you have to meticulously obey every single instruction in the 56 pages of  In his columns, Indiana skewered the art world’s bloated egos and grotesque superficiality, but he was interested, above all, in scrutinizing who held power and how it was deployed. In a particularly trenchant essay on Richard Serra’s lawsuit against the General Services Administration—the government agency that had commissioned his 1981 public sculpture Tilted Arc for the plaza outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Manhattan and, at the urging of the people who worked there, now planned to remove it against the artist’s wishes—Indiana chides Serra and his defenders for their naivete: “Who on earth did these people think they were dealing with in the first place?” he asks. “If you are so enamored of [power] that you regularly ornament its dinner tables, ride cackling through the night in its limousines, and sign worthless contracts with it, it is no problem of mine or anyone else’s if power decides, one bored afternoon, to add you to the menu instead of inviting you to eat.”

In his columns, Indiana skewered the art world’s bloated egos and grotesque superficiality, but he was interested, above all, in scrutinizing who held power and how it was deployed. In a particularly trenchant essay on Richard Serra’s lawsuit against the General Services Administration—the government agency that had commissioned his 1981 public sculpture Tilted Arc for the plaza outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Manhattan and, at the urging of the people who worked there, now planned to remove it against the artist’s wishes—Indiana chides Serra and his defenders for their naivete: “Who on earth did these people think they were dealing with in the first place?” he asks. “If you are so enamored of [power] that you regularly ornament its dinner tables, ride cackling through the night in its limousines, and sign worthless contracts with it, it is no problem of mine or anyone else’s if power decides, one bored afternoon, to add you to the menu instead of inviting you to eat.” Omnipresent social media places a claim on our elapsed time, our fractured lives. We’re all sad in our very own way. As there are no lulls or quiet moments anymore, the result is fatigue, depletion and loss of energy. We’re becoming obsessed with waiting. How long have you been forgotten by your love ones? Time, meticulously measured on every app, tells us right to our face. Chronos hurts. Should I post something to attract attention and show I’m still here? Nobody likes me anymore. As the random messages keep relentlessly piling in, there’s no way to halt them, to take a moment and think it all through.

Omnipresent social media places a claim on our elapsed time, our fractured lives. We’re all sad in our very own way. As there are no lulls or quiet moments anymore, the result is fatigue, depletion and loss of energy. We’re becoming obsessed with waiting. How long have you been forgotten by your love ones? Time, meticulously measured on every app, tells us right to our face. Chronos hurts. Should I post something to attract attention and show I’m still here? Nobody likes me anymore. As the random messages keep relentlessly piling in, there’s no way to halt them, to take a moment and think it all through. The title of Ferruccio Busoni’s 1907 manifesto Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music might suggest that the Italian pianist-composer would be looking to the future, yet many of its philosophical passages find him lingering in the past. Writing out “of convictions long held and slowly matured” (he was 41 at the time), Busoni extolled the virtues of the Baroque and classical ages, Bach and Beethoven being the exemplars—in “spirit and emotion they will probably remain unexcelled.” Busoni’s embrace of the past, however, was no rejection of modernity. “Among both ‘modern’ and ‘old’ works,” he wrote, “we find good and bad, genuine and spurious. There is nothing properly modern—only things which have come into being earlier or later; longer in bloom, or sooner withered. The Modern and the Old have always been.” Past and present, tradition and experiment—all could happily coexist in art. Thus, in more or less the same breath, Busoni could praise the elegance of Mozartian classicism while pondering some avant-garde technique, such as microtonal harmony. What mattered most of all were spirit and emotion; “he who mounts to their uttermost heights,” the musician wrote, “will always tower above the crowd.”

The title of Ferruccio Busoni’s 1907 manifesto Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music might suggest that the Italian pianist-composer would be looking to the future, yet many of its philosophical passages find him lingering in the past. Writing out “of convictions long held and slowly matured” (he was 41 at the time), Busoni extolled the virtues of the Baroque and classical ages, Bach and Beethoven being the exemplars—in “spirit and emotion they will probably remain unexcelled.” Busoni’s embrace of the past, however, was no rejection of modernity. “Among both ‘modern’ and ‘old’ works,” he wrote, “we find good and bad, genuine and spurious. There is nothing properly modern—only things which have come into being earlier or later; longer in bloom, or sooner withered. The Modern and the Old have always been.” Past and present, tradition and experiment—all could happily coexist in art. Thus, in more or less the same breath, Busoni could praise the elegance of Mozartian classicism while pondering some avant-garde technique, such as microtonal harmony. What mattered most of all were spirit and emotion; “he who mounts to their uttermost heights,” the musician wrote, “will always tower above the crowd.” Neuroscientists have for the first time discovered differences between the ‘software’ of humans and monkey brains, using a technique that tracks single neurons. They found that human brains trade off ‘robustness’ — a measure of how synchronized neuron signals are — for greater efficiency in information processing. The researchers hypothesize that the results might help to explain humans’ unique intelligence, as well as their susceptibility to psychiatric disorders. The findings were published in Cell

Neuroscientists have for the first time discovered differences between the ‘software’ of humans and monkey brains, using a technique that tracks single neurons. They found that human brains trade off ‘robustness’ — a measure of how synchronized neuron signals are — for greater efficiency in information processing. The researchers hypothesize that the results might help to explain humans’ unique intelligence, as well as their susceptibility to psychiatric disorders. The findings were published in Cell