Asad Haider at n+1:

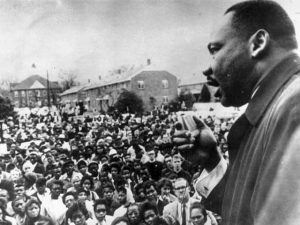

King was not the empty symbol Reagan and others claimed he was. He was a revolutionary, if one committed to nonviolence. But nonviolence does not exhaust his philosophy. As political theorist Brandon M. Terry puts it, King was not only an icon, but “a vital political thinker.” A half a century ago, Terry argues, King theorized the foundations of racism in a way that vastly surpasses the fashionable contemporary ideologies that “treat racism as near-immutable and overstate its explanatory effects.” As Terry points out, King understood that the racial question was overdetermined by wage stagnation, the declining power of organized labor, and the expulsion of workers from employment by automation. King had come to believe that transforming this structural injustice could only be achieved through mass civil disobedience.

King was not the empty symbol Reagan and others claimed he was. He was a revolutionary, if one committed to nonviolence. But nonviolence does not exhaust his philosophy. As political theorist Brandon M. Terry puts it, King was not only an icon, but “a vital political thinker.” A half a century ago, Terry argues, King theorized the foundations of racism in a way that vastly surpasses the fashionable contemporary ideologies that “treat racism as near-immutable and overstate its explanatory effects.” As Terry points out, King understood that the racial question was overdetermined by wage stagnation, the declining power of organized labor, and the expulsion of workers from employment by automation. King had come to believe that transforming this structural injustice could only be achieved through mass civil disobedience.

As a theorist of inequality, King is our contemporary. But he was also a philosopher of equality, and thus of emancipation. At the core of his thought one finds the political subjectivity that the civil rights struggle was helping to engender. Important as his final year was, the radical outlines of this project are visible from 1955 to 1963, as King was drawn deeper into political activism and answered the call to engage in a political sequence that exceeded the boundaries of the existing situation.

more here.

David Wojnarowicz did not write dark fantasy. He wrote real life. In The Waterfront Journals he brilliantly captures electric tales from the mouths of strangers, those he described as “junkies, prostitutes, male hustlers, truck drivers, hobos, young outlaws, runaway kids, criminal types”, whose lives echo his own ostracized existence. He was thirteen when he was first paid for sex and sixteen when he started “turning tricks” regularly. His mother kicked him out of the house. By the time Wojnarowicz came out to friends in New York, he was in his early twenties. He was on the cusp of finding his voice as a writer and his confidence as an artist. It was the mid-1970s.

David Wojnarowicz did not write dark fantasy. He wrote real life. In The Waterfront Journals he brilliantly captures electric tales from the mouths of strangers, those he described as “junkies, prostitutes, male hustlers, truck drivers, hobos, young outlaws, runaway kids, criminal types”, whose lives echo his own ostracized existence. He was thirteen when he was first paid for sex and sixteen when he started “turning tricks” regularly. His mother kicked him out of the house. By the time Wojnarowicz came out to friends in New York, he was in his early twenties. He was on the cusp of finding his voice as a writer and his confidence as an artist. It was the mid-1970s.  When a sentence isn’t right, I feel it immediately in my back. I’ve said this before. Sometimes I can’t type fast enough to keep up with my thoughts and a specific word disappears from my train of thought forever. Sometimes my body has enough energy to take me to a translation workshop at a friend’s home and my translation is changed for it. Sometimes my body is tired from my day job and I work half as quickly as I used to. Sometimes my body catches cold and my brain muddles words on the page. Once I had a translation deadline to meet but I had just had my tonsils removed and could barely make out the page through the muck of medication. I realized shortly after that I had wound up with something that was half truth and half lie.

When a sentence isn’t right, I feel it immediately in my back. I’ve said this before. Sometimes I can’t type fast enough to keep up with my thoughts and a specific word disappears from my train of thought forever. Sometimes my body has enough energy to take me to a translation workshop at a friend’s home and my translation is changed for it. Sometimes my body is tired from my day job and I work half as quickly as I used to. Sometimes my body catches cold and my brain muddles words on the page. Once I had a translation deadline to meet but I had just had my tonsils removed and could barely make out the page through the muck of medication. I realized shortly after that I had wound up with something that was half truth and half lie. By her own account, writing wasn’t easy for Francine du Plessix Gray, who died last Sunday at the age of eighty-eight. As she told Regina Weinreich in her 1987

By her own account, writing wasn’t easy for Francine du Plessix Gray, who died last Sunday at the age of eighty-eight. As she told Regina Weinreich in her 1987  How did I know my anxiety had gotten the better of me? When I found myself taking meticulous notes on a forthcoming book by Erica Feldmann called HAUSMAGICK: Transform Your Home With Witchcraft (HarperOne, $25.99, available in March). The year 2018 hadn’t been so great, what with the death of a husband and, possibly, a republic. Maybe 2019 would be better if I bought certain purifying elements for my home. The right crystals, sage sticks and — salt? Apparently, you can sprinkle salt around the house after a person with “toxic energy” visits. Attention future dates: If you see me reaching for the shaker as you’re leaving, you know things haven’t gone well. If my nerves are frayed, I take cold comfort in knowing I’m not alone. Whether it’s our political situation, the jangling distractions of everyday life or the not-irrational sense that mankind’s need to find another planet isn’t just a sci-fi plotline, we seem to be in the midst of one massive freakout.

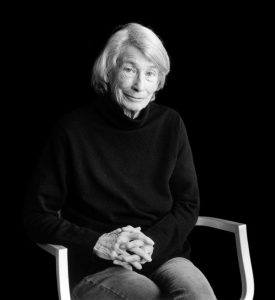

How did I know my anxiety had gotten the better of me? When I found myself taking meticulous notes on a forthcoming book by Erica Feldmann called HAUSMAGICK: Transform Your Home With Witchcraft (HarperOne, $25.99, available in March). The year 2018 hadn’t been so great, what with the death of a husband and, possibly, a republic. Maybe 2019 would be better if I bought certain purifying elements for my home. The right crystals, sage sticks and — salt? Apparently, you can sprinkle salt around the house after a person with “toxic energy” visits. Attention future dates: If you see me reaching for the shaker as you’re leaving, you know things haven’t gone well. If my nerves are frayed, I take cold comfort in knowing I’m not alone. Whether it’s our political situation, the jangling distractions of everyday life or the not-irrational sense that mankind’s need to find another planet isn’t just a sci-fi plotline, we seem to be in the midst of one massive freakout.  “Wild Geese” was trending on Twitter on Thursday, and poetry lovers — not naturalists or ornithologists — were responsible. Mary Oliver, arguably America’s most beloved best-selling poet, had died earlier in the day, at the age of 83. Her poem “Wild Geese,” from her 1986 collection

“Wild Geese” was trending on Twitter on Thursday, and poetry lovers — not naturalists or ornithologists — were responsible. Mary Oliver, arguably America’s most beloved best-selling poet, had died earlier in the day, at the age of 83. Her poem “Wild Geese,” from her 1986 collection

While away on vacation, I heard last week the sad news of the death last week of Michael Atiyah, at the age of 89. Atiyah was both a truly great mathematician and a wonderful human being. In his mathematical work he simultaneously covered a wide range of different fields, often making deep connections between them and providing continual new evidence of the unity of mathematics. This unifying vision also encompassed physics, and the entire field of topological quantum field theory was one result.

While away on vacation, I heard last week the sad news of the death last week of Michael Atiyah, at the age of 89. Atiyah was both a truly great mathematician and a wonderful human being. In his mathematical work he simultaneously covered a wide range of different fields, often making deep connections between them and providing continual new evidence of the unity of mathematics. This unifying vision also encompassed physics, and the entire field of topological quantum field theory was one result. A FEW DAYS before the 2016 election, journalist Andrew Sullivan wrote this about Donald Trump: “He has no concept of a nonzero-sum engagement, in which a deal can be beneficial for both sides. A win-win scenario is intolerable to him, because mastery of others is the only moment when he is psychically at peace.”

A FEW DAYS before the 2016 election, journalist Andrew Sullivan wrote this about Donald Trump: “He has no concept of a nonzero-sum engagement, in which a deal can be beneficial for both sides. A win-win scenario is intolerable to him, because mastery of others is the only moment when he is psychically at peace.” Last Wednesday, the conservative talk show host Tucker Carlson started a fire on the right after airing a prolonged

Last Wednesday, the conservative talk show host Tucker Carlson started a fire on the right after airing a prolonged  The first literary anniversary of 2019 will be one of the biggest: Jan. 1 marks the centenary of J.D. Salinger. (To mark the occasion, his four books are being

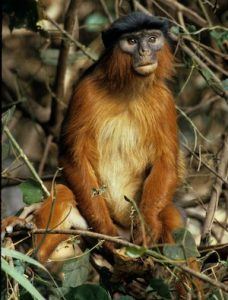

The first literary anniversary of 2019 will be one of the biggest: Jan. 1 marks the centenary of J.D. Salinger. (To mark the occasion, his four books are being  For years I spent my days, from before dawn until after dusk, following a troop of endangered red colobus monkeys around a small West African forest. For the most part the simian soap opera taking place above my head was based around everyday practical domestic themes like gorging; sleeping; snacking; resting; leaping; and forming and maintaining alliances. But, as with many soap operas, from time to time life here became totally unfocused and utterly confusing. The plots—and there were many—often drifted: sometimes boring, sometimes sitcom, sometimes rom-com, sometimes melodrama, sometimes kill-‘em-dead bloody action and sometimes high scary political drama. The characters, with enough variety to delight any casting director, ranged from gentle to not-so-nice, helpful to nasty, benevolent to downright wicked.

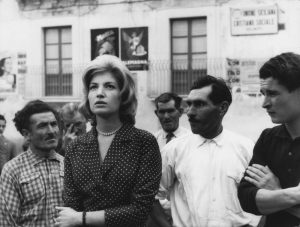

For years I spent my days, from before dawn until after dusk, following a troop of endangered red colobus monkeys around a small West African forest. For the most part the simian soap opera taking place above my head was based around everyday practical domestic themes like gorging; sleeping; snacking; resting; leaping; and forming and maintaining alliances. But, as with many soap operas, from time to time life here became totally unfocused and utterly confusing. The plots—and there were many—often drifted: sometimes boring, sometimes sitcom, sometimes rom-com, sometimes melodrama, sometimes kill-‘em-dead bloody action and sometimes high scary political drama. The characters, with enough variety to delight any casting director, ranged from gentle to not-so-nice, helpful to nasty, benevolent to downright wicked. Antonioni films typically featured jaded lovers in middle-class urban settings, their lives blighted by quiet desperation, joyless sex and existential ennui. His open-ended plots were elliptical, elusive and experimental, providing rich material for both his most ardent admirers and harshest critics. Inevitably, after an almost unblemished run of classic films spanning the 1960s and 70s, shifting fashion and ill health forced him into semi-retirement. It makes perfect sense that he spent his twilight years painting big, bold, colourful abstract art.

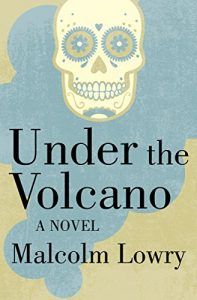

Antonioni films typically featured jaded lovers in middle-class urban settings, their lives blighted by quiet desperation, joyless sex and existential ennui. His open-ended plots were elliptical, elusive and experimental, providing rich material for both his most ardent admirers and harshest critics. Inevitably, after an almost unblemished run of classic films spanning the 1960s and 70s, shifting fashion and ill health forced him into semi-retirement. It makes perfect sense that he spent his twilight years painting big, bold, colourful abstract art. The ultimate tragedy of Under the Volcano is that of humanity’s wasted potential. Can, Lowry pondered, the psyche repair itself? We are capable of such great things, yet we choose mollification and comfort over almost anything—sometimes even over life itself. “I love hell,” Firmin claims. “I can’t wait to get back there. In fact I’m running, I’m almost back there already.” Under the Volcano is Firmin’s attempt to reckon with himself. He is alone, alienated and is finally unable to square himself with the world he has built for himself within the world he has, in many respects, stolen from others. And, in this, he has everything in common with those around him but, from Firmin’s point of view, the other characters are often reduced to minor characters, walk-ons. The only character that truly comforts Firmin is the beverage waiting before him. This minimization is not only Firmin’s: Each of the novel’s characters, in different ways, attempts to reduce the other to satiate the self.

The ultimate tragedy of Under the Volcano is that of humanity’s wasted potential. Can, Lowry pondered, the psyche repair itself? We are capable of such great things, yet we choose mollification and comfort over almost anything—sometimes even over life itself. “I love hell,” Firmin claims. “I can’t wait to get back there. In fact I’m running, I’m almost back there already.” Under the Volcano is Firmin’s attempt to reckon with himself. He is alone, alienated and is finally unable to square himself with the world he has built for himself within the world he has, in many respects, stolen from others. And, in this, he has everything in common with those around him but, from Firmin’s point of view, the other characters are often reduced to minor characters, walk-ons. The only character that truly comforts Firmin is the beverage waiting before him. This minimization is not only Firmin’s: Each of the novel’s characters, in different ways, attempts to reduce the other to satiate the self. People who tweet in their jobs—let’s say 21st century journalists, just for example—might say that writing two million tweets represents a daunting challenge. That’s the rough number,

People who tweet in their jobs—let’s say 21st century journalists, just for example—might say that writing two million tweets represents a daunting challenge. That’s the rough number,  We humans have always experienced an odd — and oddly deep — connection between the mental worlds and physical worlds we inhabit, especially when it comes to memory. We’re good at remembering landmarks and settings, and if we give our memories a location for context, hanging on to them becomes easier. To remember long speeches, ancient Greek and Roman orators imagined wandering through “memory palaces” full of reminders. Modern memory contest champions still use that technique to “place” long lists of numbers, names and other pieces of information.

We humans have always experienced an odd — and oddly deep — connection between the mental worlds and physical worlds we inhabit, especially when it comes to memory. We’re good at remembering landmarks and settings, and if we give our memories a location for context, hanging on to them becomes easier. To remember long speeches, ancient Greek and Roman orators imagined wandering through “memory palaces” full of reminders. Modern memory contest champions still use that technique to “place” long lists of numbers, names and other pieces of information.