Amit Chaudhuri at n+1:

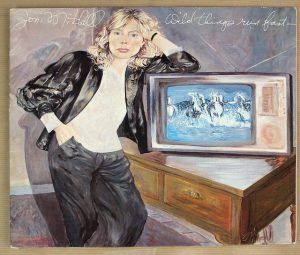

AROUND 2014, I began to talk to friends about Joni and was disappointed—surprised—by how little they knew. These were people who listened to music. I had a conversation about her with a highly accomplished ex-student in New York, a writer who had musical training, who thought I was talking about Janis Joplin. This was related to a problem: the plethora of Js among women musicians of the time, which led to their conflation into a genre. Janis Joplin, Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell: the last three especially were seen as interchangeable. Even if I put down my ex-student’s confusion to uncharacteristic generational ignorance, I found that, on mentioning Joni to a contemporary I had to work hard to distinguish her from Joan Baez. My friend had dismissed—not in the sense of “rejected,” but “taxonomized”—Joni as being part of a miscellany of singers with long, straight hair, high, clear voices, and a sincerity that shone brightly in the mass protests of the late ’60s. Visually, in her early acoustic performances with guitar, and even in her singing, she appropriated the folk singer’s persona to the point of parody, while the songwriting was absolutely unexpected. To prove this to my friend, I played her “Rainy Night House” and “Chinese Café / Unchained Melody.” It became clear in twenty seconds that Mitchell was not Joan Baez.

AROUND 2014, I began to talk to friends about Joni and was disappointed—surprised—by how little they knew. These were people who listened to music. I had a conversation about her with a highly accomplished ex-student in New York, a writer who had musical training, who thought I was talking about Janis Joplin. This was related to a problem: the plethora of Js among women musicians of the time, which led to their conflation into a genre. Janis Joplin, Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell: the last three especially were seen as interchangeable. Even if I put down my ex-student’s confusion to uncharacteristic generational ignorance, I found that, on mentioning Joni to a contemporary I had to work hard to distinguish her from Joan Baez. My friend had dismissed—not in the sense of “rejected,” but “taxonomized”—Joni as being part of a miscellany of singers with long, straight hair, high, clear voices, and a sincerity that shone brightly in the mass protests of the late ’60s. Visually, in her early acoustic performances with guitar, and even in her singing, she appropriated the folk singer’s persona to the point of parody, while the songwriting was absolutely unexpected. To prove this to my friend, I played her “Rainy Night House” and “Chinese Café / Unchained Melody.” It became clear in twenty seconds that Mitchell was not Joan Baez.

more here.

Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some

Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some  Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “

Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “ In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale.

In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale. To those convinced that a secretive cabal controls the world, the usual suspects are Illuminati, Lizard People, or “globalists.” They are wrong, naturally. There is no secret society shaping every major decision and determining the direction of human history. There is, however, McKinsey & Company.

To those convinced that a secretive cabal controls the world, the usual suspects are Illuminati, Lizard People, or “globalists.” They are wrong, naturally. There is no secret society shaping every major decision and determining the direction of human history. There is, however, McKinsey & Company. A couple of months ago, Twitter user @emrazz asked women

A couple of months ago, Twitter user @emrazz asked women  An army unit known as the “Six Triple Eight” had a specific mission in

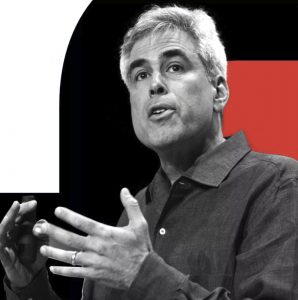

An army unit known as the “Six Triple Eight” had a specific mission in  Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU

Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind and professor at NYU IN A SERIES

IN A SERIES  Grime music is catharsis delivered from a vertiginous height. Born and bred in London’s inner city housing projects in the early 2000’s, among a Black youth subculture that drew more on Jamaican reggae than American rap, grime was a product of confinement. London’s social housing tower blocks, in which many of grime’s pioneers grew up, became synonymous with the genre’s grittiness and hyperlocal roots, but they were also essential to the music’s distribution. Grime was first popularized by pirate radio stations broadcast from illegal transmitters and squatted “studios” erected on the rooftops of 20- and 30-story buildings. Up there, elevated from their impoverished upbringings, grime’s founders found space to breathe. What they created was unapologetically strange and uncompromising: music built from beats too irregular to dance to, rapping too fast to be intelligible on the radio, lyrics full of niche slang and swear words, and songs not geared around hooks and choruses. Moreover, all of this was produced by artists unwilling to play with a British music industry focused on developing homegrown guitar bands and importing rap and R&B from the United States.

Grime music is catharsis delivered from a vertiginous height. Born and bred in London’s inner city housing projects in the early 2000’s, among a Black youth subculture that drew more on Jamaican reggae than American rap, grime was a product of confinement. London’s social housing tower blocks, in which many of grime’s pioneers grew up, became synonymous with the genre’s grittiness and hyperlocal roots, but they were also essential to the music’s distribution. Grime was first popularized by pirate radio stations broadcast from illegal transmitters and squatted “studios” erected on the rooftops of 20- and 30-story buildings. Up there, elevated from their impoverished upbringings, grime’s founders found space to breathe. What they created was unapologetically strange and uncompromising: music built from beats too irregular to dance to, rapping too fast to be intelligible on the radio, lyrics full of niche slang and swear words, and songs not geared around hooks and choruses. Moreover, all of this was produced by artists unwilling to play with a British music industry focused on developing homegrown guitar bands and importing rap and R&B from the United States. A crisis of this magnitude almost invariably reveals wider dysfunctions, and so it has been with Macron’s debacle with the gilets jaunes. The President seemed oblivious to the plight of the provinces, and unable to show any personal empathy with the lives of ordinary citizens. Visiting all corners of the territory and making an emotional connection with the people are key functions of the French republican monarch. De Gaulle managed this with his systematic tournées across small towns and villages: by the end of his first term, he had visited every metropolitan département. The very incarnation of this esprit de proximité was Jacques Chirac, who genuinely delighted in his encounters with the public, especially when they afforded opportunities to sample tasty local victuals. Macron, in contrast, has failed to cultivate these organic (and gastronomical) ties with the citizenry. He has also communicated very patchily, with long periods of Olympian silence combined with clumsy off-the-cuff interventions – as when he grumbled about his compatriots’ “Gaulois tendency to resist change”, or when he told an unemployed man that he could find a job by “just crossing the street”. In his December 10 speech, he expressed his sorrow for having “hurt” the French people by “some of his words”, and for seeming “indifferent” to their everyday concerns. This is one of the areas where his combination of intellectual superiority and political inexperience – he never held elected office before becoming President – have come back to haunt him.

A crisis of this magnitude almost invariably reveals wider dysfunctions, and so it has been with Macron’s debacle with the gilets jaunes. The President seemed oblivious to the plight of the provinces, and unable to show any personal empathy with the lives of ordinary citizens. Visiting all corners of the territory and making an emotional connection with the people are key functions of the French republican monarch. De Gaulle managed this with his systematic tournées across small towns and villages: by the end of his first term, he had visited every metropolitan département. The very incarnation of this esprit de proximité was Jacques Chirac, who genuinely delighted in his encounters with the public, especially when they afforded opportunities to sample tasty local victuals. Macron, in contrast, has failed to cultivate these organic (and gastronomical) ties with the citizenry. He has also communicated very patchily, with long periods of Olympian silence combined with clumsy off-the-cuff interventions – as when he grumbled about his compatriots’ “Gaulois tendency to resist change”, or when he told an unemployed man that he could find a job by “just crossing the street”. In his December 10 speech, he expressed his sorrow for having “hurt” the French people by “some of his words”, and for seeming “indifferent” to their everyday concerns. This is one of the areas where his combination of intellectual superiority and political inexperience – he never held elected office before becoming President – have come back to haunt him. In 724 A.D., the twenty-three-year-old poet Li Bai got on a boat and set out from his home region of Shu, today’s Sichuan province, in search of Daoist learnings and a political career. He wasn’t headed anywhere in particular. Instead, he began a life of roaming—hiking up mountains to Daoist sites, meeting men of letters all over the country, and leaving behind hundreds of poems about his travels, his solitude, his friends, the moon, and the pleasures of drinking wine. In the centuries since, Li’s verse, by turns playful and profound, has made him China’s most beloved poet.

In 724 A.D., the twenty-three-year-old poet Li Bai got on a boat and set out from his home region of Shu, today’s Sichuan province, in search of Daoist learnings and a political career. He wasn’t headed anywhere in particular. Instead, he began a life of roaming—hiking up mountains to Daoist sites, meeting men of letters all over the country, and leaving behind hundreds of poems about his travels, his solitude, his friends, the moon, and the pleasures of drinking wine. In the centuries since, Li’s verse, by turns playful and profound, has made him China’s most beloved poet. During a six-month period in 1889, nearly 900,000 people descended upon the sprawling Universal Exposition in Paris, the fourth world’s fair to be held in the city, this one constructed in the shadows of the new Eiffel Tower. For the average Parisian strolling down the Esplanade des Invalides, the sight of a Tunisian palace, an Algerian bazaar, or a Cambodian pagoda would have meant pure enchantment, and nobody was more enchanted than Claude Debussy. Inside a replica of a Javanese village, the 26-year-old composer encountered the ensemble of bronze metallophones, gongs, and other instruments known as a gamelan, the musicians in the pavilion joined by a male singer and four young female dancers. For an artist recoiling from the rigid orthodoxy of the conservatory, the music’s bright, sensuous timbres, its feeling of spaciousness, and its vaguely pentatonic scales offered Debussy a path toward something new, even if he struggled to make sense of what he heard in the context of western harmony and counterpoint.

During a six-month period in 1889, nearly 900,000 people descended upon the sprawling Universal Exposition in Paris, the fourth world’s fair to be held in the city, this one constructed in the shadows of the new Eiffel Tower. For the average Parisian strolling down the Esplanade des Invalides, the sight of a Tunisian palace, an Algerian bazaar, or a Cambodian pagoda would have meant pure enchantment, and nobody was more enchanted than Claude Debussy. Inside a replica of a Javanese village, the 26-year-old composer encountered the ensemble of bronze metallophones, gongs, and other instruments known as a gamelan, the musicians in the pavilion joined by a male singer and four young female dancers. For an artist recoiling from the rigid orthodoxy of the conservatory, the music’s bright, sensuous timbres, its feeling of spaciousness, and its vaguely pentatonic scales offered Debussy a path toward something new, even if he struggled to make sense of what he heard in the context of western harmony and counterpoint. From where I work at the University of Sydney, you cannot see the ocean. However, in Australia, the ocean is part of our national consciousness. This is perhaps why I think of the research literature as an ocean, linking researchers in disparate yet ultimately connected fields. Just as there is growing alarm about our rising, polluted oceans, scientists are increasingly talking about the swelling research literature and its contamination by incorrect research results.

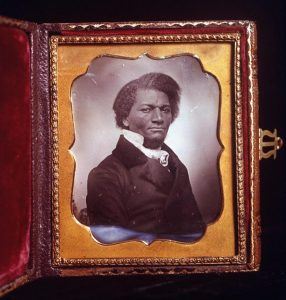

From where I work at the University of Sydney, you cannot see the ocean. However, in Australia, the ocean is part of our national consciousness. This is perhaps why I think of the research literature as an ocean, linking researchers in disparate yet ultimately connected fields. Just as there is growing alarm about our rising, polluted oceans, scientists are increasingly talking about the swelling research literature and its contamination by incorrect research results. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass On Monday, a trail runner in Colorado was attacked by a mountain lion. While fighting to defend his life, the man managed to kill the lion. This is how he did that.

On Monday, a trail runner in Colorado was attacked by a mountain lion. While fighting to defend his life, the man managed to kill the lion. This is how he did that. Researchers in

Researchers in