Sheila Marikar in More Intelligent Life:

On a Monday afternoon in December, Sarah Jones, a Tony award-winning playwright and impressionist, sits at a flimsy metal table in Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, a cavernous food hall hawking a vast array of cuisine: grass-fed lamb, vegan ramen, tacos, acai bowls. Around her, scruffy workers in baseball caps take their lunches next to corporate types in suits. In a city where the car culture promotes a gas-guzzling form of isolation, the market offers an alternative atmosphere: it buzzes with the energy of happenstance meetings.

On a Monday afternoon in December, Sarah Jones, a Tony award-winning playwright and impressionist, sits at a flimsy metal table in Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, a cavernous food hall hawking a vast array of cuisine: grass-fed lamb, vegan ramen, tacos, acai bowls. Around her, scruffy workers in baseball caps take their lunches next to corporate types in suits. In a city where the car culture promotes a gas-guzzling form of isolation, the market offers an alternative atmosphere: it buzzes with the energy of happenstance meetings.

This is why Jones chose it for the first day of shooting “She the People”, her forthcoming television series which will take on topics like gender, race, sex, power and ethnic identity in much the same way that the chef Anthony Bourdain documented global cuisine. In each episode Jones will travel to a different part of the world, from Amsterdam’s red-light district to the US-Mexico border, drawing these subjects out through the lives of ordinary people. “Every episode is going to put Sarah on the front lines of an issue,” says Justin Wilkes, the president of Imagine Documentaries, which is producing the show.

But Jones is no ordinary interviewer: she’s an impressionist, who morphs between characters seamlessly. Watching her is like observing a master magician at close range, as you try and fail to catch the moment when the trick happens. These transformations make the often dry social issues she tackles in her shows relatable, poignant and hilarious, and have turned Jones into one of America’s most subtle examiners of stereotypes and clichés. That art has defined her stage work; this autumn, TV audiences will be able to enjoy it too.

More here.

Argentinian artist Mirtha Dermisache produced “a voluminous body of illegible writings.” This phrase from the editors’ brief afterward is in itself so evocative I can hardly go further, that body light and aloft, setting sail on an invisible current of the thoughts beneath words, the feelings beneath skin.

Argentinian artist Mirtha Dermisache produced “a voluminous body of illegible writings.” This phrase from the editors’ brief afterward is in itself so evocative I can hardly go further, that body light and aloft, setting sail on an invisible current of the thoughts beneath words, the feelings beneath skin. Certainly, even as Cunard’s own work – long overlooked in favour of works about her, including a number of biographies – has recently begun to be recognized and republished, attention has still tended to focus on those of her writings with links to the more outré figures and avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s. Of her poetry, it is the long Parallax (1925), a response to The Waste Land (and, like T. S. Eliot’s poem, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press), that is best known – only partly because it is her best. Meanwhile, her prose, which includes extensive political journalism and several works of memoir, remains largely out of print, and her extensive career as an anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-imperial writer and activist is often characterized as a series of dilettantish enthusiasms.

Certainly, even as Cunard’s own work – long overlooked in favour of works about her, including a number of biographies – has recently begun to be recognized and republished, attention has still tended to focus on those of her writings with links to the more outré figures and avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s. Of her poetry, it is the long Parallax (1925), a response to The Waste Land (and, like T. S. Eliot’s poem, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press), that is best known – only partly because it is her best. Meanwhile, her prose, which includes extensive political journalism and several works of memoir, remains largely out of print, and her extensive career as an anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-imperial writer and activist is often characterized as a series of dilettantish enthusiasms. Jhabvala may have written of Indians, but she wrote largely for the Western Hemisphere. “I have no fans in India,” she

Jhabvala may have written of Indians, but she wrote largely for the Western Hemisphere. “I have no fans in India,” she  The trade in ideas, technologies, art and culture between Africa and her partners flowed both ways, a reality that was accentuated by the slavery trade – something that Green explores in great depth. Not only did African goods and commodities pulse through the arteries of the Atlantic world, cultural knowledge and intellectual capital was taken to the New World in the minds of the millions of human beings who were themselves commodified and exchanged. The Maroons, communities of escaped slaves that emerged in Jamaica, Panama and elsewhere, fought their wars using military theories they had learnt on the continent of their birth. Likewise, the rice plantations of South Carolina were cultivated using not just African labour but also African knowledge. This expertise was intentionally transplanted into American soil by British slave traders who had enslaved thousands of people from the rice-growing regions of Sierra Leone. These Africans were kidnapped to order, their minds as valuable a commodity as their bodies.

The trade in ideas, technologies, art and culture between Africa and her partners flowed both ways, a reality that was accentuated by the slavery trade – something that Green explores in great depth. Not only did African goods and commodities pulse through the arteries of the Atlantic world, cultural knowledge and intellectual capital was taken to the New World in the minds of the millions of human beings who were themselves commodified and exchanged. The Maroons, communities of escaped slaves that emerged in Jamaica, Panama and elsewhere, fought their wars using military theories they had learnt on the continent of their birth. Likewise, the rice plantations of South Carolina were cultivated using not just African labour but also African knowledge. This expertise was intentionally transplanted into American soil by British slave traders who had enslaved thousands of people from the rice-growing regions of Sierra Leone. These Africans were kidnapped to order, their minds as valuable a commodity as their bodies. Edmundson has written an admirably concise yet powerful book. It blends a critical account of Rawls’ work with an original case for democratic socialism hewn from Rawlsian stone. In my opinion, this case has some flaws but it remains a timely contribution to the enduring quest for justice and social stability.

Edmundson has written an admirably concise yet powerful book. It blends a critical account of Rawls’ work with an original case for democratic socialism hewn from Rawlsian stone. In my opinion, this case has some flaws but it remains a timely contribution to the enduring quest for justice and social stability. Take a look at the world poverty clock, which shows in real time the fall in the number of people living in extreme poverty. Or consider two recent bestsellers –

Take a look at the world poverty clock, which shows in real time the fall in the number of people living in extreme poverty. Or consider two recent bestsellers –  ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it.

ON VALENTINE’S DAY 1989, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, declared a death sentence on British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses, along with any who helped its release: “I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.” The Ayatollah accused Rushdie of blasphemy, of sullying Islam and its prophet Muhammad, though many saw it as a desperate cry for popular support after a humiliating decade of war with Iraq. There followed riots, demonstrations, and book burnings across Europe and the Middle East. Death threats poured in. Viking Penguin, Rushdie’s UK publisher, was threatened with bombings. The author himself was forced into hiding under the pseudonym “Joseph Anton,” a mash-up of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov and the title of Rushdie’s 2012 memoir of the controversy. The media and public still remember it as “The Rushdie Affair,” though most people born after the 1980s have never heard of it. Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’

Debates around the politics of Trump and other new-right leaders have led to an explosion of historical analogizing, with the experience of the 1930s looming large. According to much of this commentary, Trump—not to mention Orbán, Kaczynski, Modi, Duterte, Erdoğan—is an authoritarian figure justifiably compared to those of the fascist era. The proponents of this view span the political spectrum, from neoconservative right and liberal mainstream to anarchist insurrectionary. The typical rhetorical device they deploy is to advance and protect the identification of Trump with fascism by way of nominal disclaimers of it. Thus for Timothy Snyder, a Cold War liberal, ‘There are differences’—yet: ‘Trump has made his debt to fascism clear from the beginning. From his initial linkage of immigrants to sexual violence to his continued identification of journalists as “enemies” . . . he has given us every clue we need.’ For Snyder’s Yale colleague, Jason Stanley, ‘I’m not arguing that Trump is a fascist leader, in the sense that he’s ruling as a fascist’—but: ‘as far as his rhetorical strategy goes, it’s very fascist.’ For their fellow liberal Richard Evans, at Cambridge: ‘It’s not the same’—however: ‘Trump is a 21st-century would-be dictator who uses the unprecedented power of social media and the Internet to spread conspiracy theories’—‘worryingly reminiscent of the fascists of the 1920s and 1930s.’ In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “

In 1995, Edward Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., published a short book called “ On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published

On Monday, the Jerusalem Post, a centrist Israeli newspaper, published  “I am not a man, I am dynamite!” Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for this kind of bombast, but most of his works are unassuming in tone, and his sentences are always plain, direct and clear as a bell. Take for instance the celebrated assault on “theorists” in his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872. Theorists, Nietzsche says, know everything there is to know about “world literature”—they can “name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts.” But instead of “plunging into the icy torrent of existence” they merely content themselves with “running nervously up and down the river bank.”

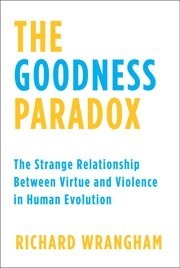

“I am not a man, I am dynamite!” Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for this kind of bombast, but most of his works are unassuming in tone, and his sentences are always plain, direct and clear as a bell. Take for instance the celebrated assault on “theorists” in his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872. Theorists, Nietzsche says, know everything there is to know about “world literature”—they can “name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts.” But instead of “plunging into the icy torrent of existence” they merely content themselves with “running nervously up and down the river bank.” DeVore had hanging in his office an 1838 quote from Darwin’s notebook: “Origin of man now proved … He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” It’s an aphorism that calls to mind one of my favorite characterizations of anthropology—philosophizing with data—and serves as a perfect introduction to the latest work of Richard Wrangham, who has come up with some of the boldest and best new ideas about human evolution.

DeVore had hanging in his office an 1838 quote from Darwin’s notebook: “Origin of man now proved … He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” It’s an aphorism that calls to mind one of my favorite characterizations of anthropology—philosophizing with data—and serves as a perfect introduction to the latest work of Richard Wrangham, who has come up with some of the boldest and best new ideas about human evolution. String theory was originally proposed as a relatively modest attempt to explain some features of strongly-interacting particles, but before too long developed into an ambitious attempt to unite all the forces of nature into a single theory. The great thing about physics is that your theories don’t always go where you want them to, and string theory has had some twists and turns along the way. One major challenge facing the theory is the fact that there are many different ways to connect the deep principles of the theory to the specifics of a four-dimensional world; all of these may actually exist out there in the world, in the form of a cosmological multiverse. Brian Greene is an accomplished string theorist as well as one of the world’s most successful popularizers and advocates for science. We talk about string theory, its cosmological puzzles and promises, and what the future might hold.

String theory was originally proposed as a relatively modest attempt to explain some features of strongly-interacting particles, but before too long developed into an ambitious attempt to unite all the forces of nature into a single theory. The great thing about physics is that your theories don’t always go where you want them to, and string theory has had some twists and turns along the way. One major challenge facing the theory is the fact that there are many different ways to connect the deep principles of the theory to the specifics of a four-dimensional world; all of these may actually exist out there in the world, in the form of a cosmological multiverse. Brian Greene is an accomplished string theorist as well as one of the world’s most successful popularizers and advocates for science. We talk about string theory, its cosmological puzzles and promises, and what the future might hold. NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER

NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER  Neanderthals disappeared from Europe roughly 40,000 years ago, and scientists are still trying to figure out why. Did disease, climate change or competition with modern humans — or maybe a combination of all three — do them in? In a recent

Neanderthals disappeared from Europe roughly 40,000 years ago, and scientists are still trying to figure out why. Did disease, climate change or competition with modern humans — or maybe a combination of all three — do them in? In a recent