Fareed Zakaria in Foreign Policy:

In 1998, as the Asian financial crisis was ravaging what had been some of the fastest-growing economies in the world, the New Yorker ran an article describing the international rescue efforts. It profiled the super-diplomat of the day, a big-idea man the Economist had recently likened to Henry Kissinger. The New Yorker went further, noting that when he arrived in Japan in June, this American official was treated “as if he were General [Douglas] MacArthur.” In retrospect, such reverence seems surprising, given that the man in question, Larry Summers, was a disheveled, somewhat awkward nerd then serving as the U.S. deputy treasury secretary. His extraordinary status owed, in part, to the fact that the United States was then (and still is) the world’s sole superpower and the fact that Summers was (and still is) extremely intelligent. But the biggest reason for Summers’s welcome was the widespread perception that he possessed a special knowledge that would save Asia from collapse. Summers was an economist.

During the Cold War, the tensions that defined the world were ideological and geopolitical. As a result, the superstar experts of that era were those with special expertise in those areas. And policymakers who could combine an understanding of both, such as Kissinger, George Kennan, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, ascended to the top of the heap, winning the admiration of both politicians and the public. Once the Cold War ended, however, geopolitical and ideological issues faded in significance, overshadowed by the rapidly expanding global market as formerly socialist countries joined the Western free trade system. All of a sudden, the most valuable intellectual training and practical experience became economics, which was seen as the secret sauce that could make and unmake nations. In 1999, after the Asian crisis abated, Time magazine ran a cover story with a photograph of Summers, U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, and U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan and the headline “The Committee to Save the World.”

In the three decades since the end of the Cold War, economics has enjoyed a kind of intellectual hegemony.

More here.

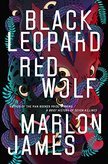

As Zachary Lazar put it in his New York Times review: “It helps that James . . . is a virtuoso at depicting violence, particularly at the beginning of this book, where we witness scene after scene of astonishing sadism, as young men and boys are impelled by savagery toward savagery of their own.” Later he writes, “The novel’s great strength is the way it conveys the degradation of Kingston’s slums.” Lazar’s praise, the elements of the novel he highlighted, would be echoed again and again in each review I read, and I can’t say he’s wrong. James ismasterful with violence and sadism, and Kingston’s slums are vividly portrayed.

As Zachary Lazar put it in his New York Times review: “It helps that James . . . is a virtuoso at depicting violence, particularly at the beginning of this book, where we witness scene after scene of astonishing sadism, as young men and boys are impelled by savagery toward savagery of their own.” Later he writes, “The novel’s great strength is the way it conveys the degradation of Kingston’s slums.” Lazar’s praise, the elements of the novel he highlighted, would be echoed again and again in each review I read, and I can’t say he’s wrong. James ismasterful with violence and sadism, and Kingston’s slums are vividly portrayed. If, as one sometimes hears, people can be divided into two groups—those who run away from violence and danger and those who run toward it—something similar could be said about ones who, like Brassaï and Caravaggio, see themselves as nocturnal beings, as opposed to those who see themselves as creatures of daylight, or even identify with that loaded appellation morning person. Some, like Sancho Panza, wish only to go to bed at twilight and to sleep undisturbed—escaping the real and imagined terrors that they perhaps sense lurk in the dark. Others, like Don Quixote, feel the compulsion to stay awake for at least part of the night, to maintain a vigil.

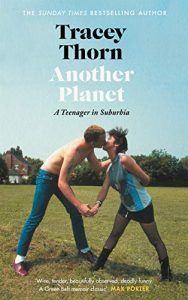

If, as one sometimes hears, people can be divided into two groups—those who run away from violence and danger and those who run toward it—something similar could be said about ones who, like Brassaï and Caravaggio, see themselves as nocturnal beings, as opposed to those who see themselves as creatures of daylight, or even identify with that loaded appellation morning person. Some, like Sancho Panza, wish only to go to bed at twilight and to sleep undisturbed—escaping the real and imagined terrors that they perhaps sense lurk in the dark. Others, like Don Quixote, feel the compulsion to stay awake for at least part of the night, to maintain a vigil. You don’t turn to Thorn’s memoirs (this is her second; she is also a New Statesman columnist) for rock ’n’ roll name-dropping, but for someone who can – to quote her quoting Updike – “give the mundane its beautiful due”. My brother-in-law says of being a fan of the band: “The only difference between them and us was that we were listening to Everything but the Girl, while they were in Everything but the Girl.” The past is another planet and the diary twinkles with the arcane poetry of lost brand names – Aqua Manda, Green Shield Stamps.

You don’t turn to Thorn’s memoirs (this is her second; she is also a New Statesman columnist) for rock ’n’ roll name-dropping, but for someone who can – to quote her quoting Updike – “give the mundane its beautiful due”. My brother-in-law says of being a fan of the band: “The only difference between them and us was that we were listening to Everything but the Girl, while they were in Everything but the Girl.” The past is another planet and the diary twinkles with the arcane poetry of lost brand names – Aqua Manda, Green Shield Stamps. Last fall it was voted America’s best-loved book. This winter it made it to Broadway, grossing more at the box office in its first full week than any other play in history. Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” became a classic the moment it was published in 1960 – a tale of racial injustice set in Depression-era Alabama told through the eyes of 6-year-old Scout. It garnered the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and its movie adaptation won three Oscars in 1963. That it has smashed theater records and risen to the top of

Last fall it was voted America’s best-loved book. This winter it made it to Broadway, grossing more at the box office in its first full week than any other play in history. Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” became a classic the moment it was published in 1960 – a tale of racial injustice set in Depression-era Alabama told through the eyes of 6-year-old Scout. It garnered the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and its movie adaptation won three Oscars in 1963. That it has smashed theater records and risen to the top of  “I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “

“I don’t want to make somebody else,” Toni Morrison’s character Sula declares, when urged to get married and have kids, “I want to make myself.” Morrison herself might have understood this to be a false dichotomy—she was a single mother of two by the time she published “ In Diego Rivera’s La creación, Nahui Olin sits among a gathering of figures that represent “the fable,” draped in gold and blue. She appears as the figure of Erotic Poetry, fitting for what she was known for at the time: her erotic writing and sexual freedom.

In Diego Rivera’s La creación, Nahui Olin sits among a gathering of figures that represent “the fable,” draped in gold and blue. She appears as the figure of Erotic Poetry, fitting for what she was known for at the time: her erotic writing and sexual freedom. A young evolutionary biologist, Barrett had come to Nebraska’s Sand Hills with a grand plan. He would build large outdoor enclosures in areas with light or dark soil, and fill them with captured mice. Over time, he would see how these rodents adapted to the different landscapes—a deliberate, real-world test of natural selection, on a scale that biologists rarely attempt.

A young evolutionary biologist, Barrett had come to Nebraska’s Sand Hills with a grand plan. He would build large outdoor enclosures in areas with light or dark soil, and fill them with captured mice. Over time, he would see how these rodents adapted to the different landscapes—a deliberate, real-world test of natural selection, on a scale that biologists rarely attempt. When

When  And yet the most surprising aspect of the tiny-house phenomenon might be that, while the lifestyle has never been more visible, real-life tiny-house dwellers are hard to find. Fewer than ten thousand of the homes are estimated to exist nationwide. The impracticalities of tiny living—shoebox-sized sinks, closetless rooms—can be daunting, but it’s not only that. There are also legal obstacles. In most states, houses built on a foundation must be at least 400 square feet. To get around that, builders have taken to putting tiny houses on wheels and building them to the less restrictive codes that apply to RVs. But many states and cities bar RVs from being parked in one place year-round. Also, when you buy a tiny house, the house is all you get; you have to either buy the land to put it on, use someone else’s for free, or find a landlord willing to lease land to you.

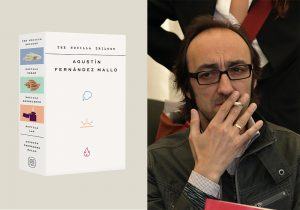

And yet the most surprising aspect of the tiny-house phenomenon might be that, while the lifestyle has never been more visible, real-life tiny-house dwellers are hard to find. Fewer than ten thousand of the homes are estimated to exist nationwide. The impracticalities of tiny living—shoebox-sized sinks, closetless rooms—can be daunting, but it’s not only that. There are also legal obstacles. In most states, houses built on a foundation must be at least 400 square feet. To get around that, builders have taken to putting tiny houses on wheels and building them to the less restrictive codes that apply to RVs. But many states and cities bar RVs from being parked in one place year-round. Also, when you buy a tiny house, the house is all you get; you have to either buy the land to put it on, use someone else’s for free, or find a landlord willing to lease land to you. In June 2007, in Seville, Spain, a conference was held under the banner “New Fictioneers: The Spanish Literary Atlas.” Around forty writers and critics came together at the Andalusian Center for Contemporary Art to discuss the conservatism they felt to be suffocating their national literature. United in their belief that the Spanish novel in particular was in a bad state, they pointed to a disregard for the increasing centrality of digital media in people’s lives and a knee-jerk resistance to anything that smacked of formal experimentation. They were mostly of a similar age, born in the twilight of the Franco regime, committed to the DIY punk ethos of the fledgling blogosphere, and more likely to claim lineage to J. G. Ballard or Jean Baudrillard than any garlanded compatriots of their own. Nonetheless, the only true point of agreement on the day was that they were not part of a unified movement. The conference’s inaugural address itself rejected any suggestion of a coherent generation—a commonplace criticism familiar in Spain ever since the clumping together, at the end of the nineteenth century, of the Generation of ’98. Within a few weeks, however, an article appeared dubbing these writers “The Nocilla Generation”: the most significant literary phenomenon of Spain’s democratic era now had a label, and it stuck.

In June 2007, in Seville, Spain, a conference was held under the banner “New Fictioneers: The Spanish Literary Atlas.” Around forty writers and critics came together at the Andalusian Center for Contemporary Art to discuss the conservatism they felt to be suffocating their national literature. United in their belief that the Spanish novel in particular was in a bad state, they pointed to a disregard for the increasing centrality of digital media in people’s lives and a knee-jerk resistance to anything that smacked of formal experimentation. They were mostly of a similar age, born in the twilight of the Franco regime, committed to the DIY punk ethos of the fledgling blogosphere, and more likely to claim lineage to J. G. Ballard or Jean Baudrillard than any garlanded compatriots of their own. Nonetheless, the only true point of agreement on the day was that they were not part of a unified movement. The conference’s inaugural address itself rejected any suggestion of a coherent generation—a commonplace criticism familiar in Spain ever since the clumping together, at the end of the nineteenth century, of the Generation of ’98. Within a few weeks, however, an article appeared dubbing these writers “The Nocilla Generation”: the most significant literary phenomenon of Spain’s democratic era now had a label, and it stuck. Complexities

Complexities  I promised God and some other responsible characters, including a bench of bishops, that I was not going to part my lips concerning the U.S. Supreme Court decision on ending segregation in the public schools of the South. But since a lot of time has passed and no one seems to touch on what to me appears to be the most important point in the hassle, I break my silence just this once. Consider me as just thinking out loud.

I promised God and some other responsible characters, including a bench of bishops, that I was not going to part my lips concerning the U.S. Supreme Court decision on ending segregation in the public schools of the South. But since a lot of time has passed and no one seems to touch on what to me appears to be the most important point in the hassle, I break my silence just this once. Consider me as just thinking out loud. A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with  In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.  47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1