Career Counseling

You can be whatever you set your mind to,

my teachers were fond of saying.

Sit down, son.

The counselor pointed to a chair,

pulling out brochures like a travel agent.

Where are you headed?

As if no destination were outside the realm of possibility;

we just had to plug it into the computer,

check flights,

book tickets far enough in advance.

You can be whatever you wish,

my father said — meaning, lawyer, teacher, engineer, MD,

RN, CPA — speaking in that voice

parents use, knowing

they’re being more understanding

than their parents were. Tell me,

what do you really want to do?

What could I say? I want to be a boy

adopted by vultures. Or a blind girl

who lives in a cave.

Or a hermit who speaks to lizards.

I wanted to be washed up,

a castaway searching

for the crew I’d been separated from,

shipwrecked on this planet,

marooned in a human body.

Maybe that was why I touched myself so often —

to see if I could feel a fragment

of who I really was, a piece of light

buried in me, broken off from the star

I spent so much energy trying to get back to.

Maybe that’s why I lit matches

and pressed the flames into my palms,

as if pain held the answer

folded up in its petals.

Maybe the only way back

was to hurt, to rub against broken glass.

What’s on your mind?

asked the doctor. Don’t be afraid. You can

tell me anything. I was thinking

of what I’d have to give up,

what every young man or woman

serious about making a living has to give up:

gazing at leaves, those elegant distractions,

or the creek’s long, run-on sentences,

its exclamations, its

parentheses, its tireless questions.

What if we made graduation a little more honest,

held a ceremony

where every eighteen-year-old dragged onto the field

all he’d hidden in his closets,

all that could prove embarrassing,

all she loved but had no excuse to hold on to anymore?

Final exams would require every student

to write down the idle thoughts

she’d promised never

to think again, every word

it excited a boy just to write:

wastrel, changeling, maelstrom, cataclysm, galaxy,

alien, naked, vampire, crucible, relic.

Fire would grade the papers,

and everybody would get the same mark,

flames correcting the notebooks

filled with spaceships

or Greek gods

or the names of sweethearts written over

and over in different scripts

or drawings of horses —

all a girl had to do was look at them, then close her eyes,

to feel the power ripping

under her, carrying her into the sky —

or pictures of dogs too important to die,

of movie stars or rock bands

into whose faces a young man or woman gazes

till afternoons open like doors

they’d thought shut tight.

You can be whatever you set your mind to.

But at what cost?

Sit down, son.

Tell me what you want to do with the rest of your life.

by Chris Bursk

from The Sun Magazine

September 1996

The human gut harbors trillions of invisible microbial inhabitants, referred to as the microbiota, that collectively produce thousands of unique small molecules. The sources and biological functions of the vast majority of these molecules are unknown. Yale researchers recently applied a new technology to uncover microbiota-derived chemicals that affect human physiology, revealing a complex network of interactions with potentially broad-reaching impacts on human health.

The human gut harbors trillions of invisible microbial inhabitants, referred to as the microbiota, that collectively produce thousands of unique small molecules. The sources and biological functions of the vast majority of these molecules are unknown. Yale researchers recently applied a new technology to uncover microbiota-derived chemicals that affect human physiology, revealing a complex network of interactions with potentially broad-reaching impacts on human health.

At 3 p.m. on a Monday afternoon, death announced it was coming for him. He was only eight years old; his cancer cells were not responding to treatment anymore. His body’s leukemic blast cell counts were doubling daily. Bone marrow was no longer making red or white blood cells, not even platelets. The marrow was only churning out cancer cells. In a process similar to churning butter, his blood was thickening with homogenous, malicious content: cancer. And like churning butter, it was exhausting work. The battered remnants of his healthy self were beaten down by chemo. And yet, every fiber pressed on.

At 3 p.m. on a Monday afternoon, death announced it was coming for him. He was only eight years old; his cancer cells were not responding to treatment anymore. His body’s leukemic blast cell counts were doubling daily. Bone marrow was no longer making red or white blood cells, not even platelets. The marrow was only churning out cancer cells. In a process similar to churning butter, his blood was thickening with homogenous, malicious content: cancer. And like churning butter, it was exhausting work. The battered remnants of his healthy self were beaten down by chemo. And yet, every fiber pressed on.

As Nicholas Money puts it in Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History, thinking of the mushroom in place of the whole mushroom-forming organism is ‘a bit like using a photograph of a large pair of testicles to represent an elephant’. (The flaw in this memorable comparison is that the spore inside a mushroom is ready to grow into next-generation fungus, so long as it’s launched into congenial conditions, whereas an elephant sperm cell only contains half the chromosomes needed to begin a baby elephant.) Like the testicle, the mushroom is just one component of an organism, relatively peripheral to the organism’s viability, if essential to the continuation of its species. Unlike the elephant testicle (and hence the force of Money’s comparison), it is the part of the organism to which human cultures have in general paid the most attention. It’s this spore-disperser, not the hard-working mycelium, that we might consider dining on, illustrating, ingesting for hallucinatory or medicinal purposes, founding a taxonomic system around, deploying in the assassination of an unlikeable Roman emperor, or photographing on our nature rambles. It’s what appears in the field guides, the cookbooks, and the mythologies.

As Nicholas Money puts it in Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History, thinking of the mushroom in place of the whole mushroom-forming organism is ‘a bit like using a photograph of a large pair of testicles to represent an elephant’. (The flaw in this memorable comparison is that the spore inside a mushroom is ready to grow into next-generation fungus, so long as it’s launched into congenial conditions, whereas an elephant sperm cell only contains half the chromosomes needed to begin a baby elephant.) Like the testicle, the mushroom is just one component of an organism, relatively peripheral to the organism’s viability, if essential to the continuation of its species. Unlike the elephant testicle (and hence the force of Money’s comparison), it is the part of the organism to which human cultures have in general paid the most attention. It’s this spore-disperser, not the hard-working mycelium, that we might consider dining on, illustrating, ingesting for hallucinatory or medicinal purposes, founding a taxonomic system around, deploying in the assassination of an unlikeable Roman emperor, or photographing on our nature rambles. It’s what appears in the field guides, the cookbooks, and the mythologies. Yet Coltrane’s commercial clout, transient or permanent, should not detract from his huge artistic stature. Next to Miles Davis, he is the post-war jazz musician most likely to be on the radar of those who do not consider themselves jazz fans. His allure as a figure entirely dedicated to, if not consumed by, his work (to the point where he was often seen in public with theory books such as Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus Of Scales And Melodic Patterns), makes him a role model for all students of “serious” music. Coltrane is the archetypal creative obsessive intent on finding unheard approaches to the building blocks of music, from the arc of his melodies to the rhythmic drive of his solos to the harmonic framework for his songs.

Yet Coltrane’s commercial clout, transient or permanent, should not detract from his huge artistic stature. Next to Miles Davis, he is the post-war jazz musician most likely to be on the radar of those who do not consider themselves jazz fans. His allure as a figure entirely dedicated to, if not consumed by, his work (to the point where he was often seen in public with theory books such as Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus Of Scales And Melodic Patterns), makes him a role model for all students of “serious” music. Coltrane is the archetypal creative obsessive intent on finding unheard approaches to the building blocks of music, from the arc of his melodies to the rhythmic drive of his solos to the harmonic framework for his songs. There is something awesomely confounding about the music of Tyshawn Sorey, the thirty-eight-year-old Newark-born composer, percussionist, pianist, and trombonist. As a critic, I feel obliged to describe what I hear, and description usually begins with categorization. Sorey’s work eludes the pinging radar of genre and style. Is it jazz? New classical music? Composition? Improvisation? Tonal? Atonal? Minimal? Maximal? Each term captures a part of what Sorey does, but far from all of it. At the same time, he is not one of those crossover artists who indiscriminately mash genres together. Even as his music shifts shape, it retains an obdurate purity of voice. T. S. Eliot’s advice seems apt: “Oh, do not ask, ‘What is it?’ / Let us go and make our visit.”

There is something awesomely confounding about the music of Tyshawn Sorey, the thirty-eight-year-old Newark-born composer, percussionist, pianist, and trombonist. As a critic, I feel obliged to describe what I hear, and description usually begins with categorization. Sorey’s work eludes the pinging radar of genre and style. Is it jazz? New classical music? Composition? Improvisation? Tonal? Atonal? Minimal? Maximal? Each term captures a part of what Sorey does, but far from all of it. At the same time, he is not one of those crossover artists who indiscriminately mash genres together. Even as his music shifts shape, it retains an obdurate purity of voice. T. S. Eliot’s advice seems apt: “Oh, do not ask, ‘What is it?’ / Let us go and make our visit.” “I’ve never cried for a building, until now,” I wrote to my aunt Lou Ann. Then I had a moment’s hesitation. Did I not cry for the World Trade Center back in 2001? I was living in New York, after all. We watched the Towers fall from a roof in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I know that I shed some tears that day. Tears of shock and grief and loss. But I was not, in truth, crying for the Towers themselves. I don’t think anyone cried for the Towers themselves. Because they were not loved. I remember a Greek friend of mine once commenting that he found the Towers ridiculous in their doubleness. He put it like this: “It is absurd that there are two of them.” One giant monstrous imposing monolith would have been enough. But to make two of them? It is like, my friend said, a couple of guys who are bragging and competing about who has the largest schlong. And then a third guy walks up and says, “I’ve got you both beat. I’ve got two of them.” But has he really won? Did he even understand the game? The Twin Towers were like that. They won the giant building game. But at what cost?

“I’ve never cried for a building, until now,” I wrote to my aunt Lou Ann. Then I had a moment’s hesitation. Did I not cry for the World Trade Center back in 2001? I was living in New York, after all. We watched the Towers fall from a roof in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I know that I shed some tears that day. Tears of shock and grief and loss. But I was not, in truth, crying for the Towers themselves. I don’t think anyone cried for the Towers themselves. Because they were not loved. I remember a Greek friend of mine once commenting that he found the Towers ridiculous in their doubleness. He put it like this: “It is absurd that there are two of them.” One giant monstrous imposing monolith would have been enough. But to make two of them? It is like, my friend said, a couple of guys who are bragging and competing about who has the largest schlong. And then a third guy walks up and says, “I’ve got you both beat. I’ve got two of them.” But has he really won? Did he even understand the game? The Twin Towers were like that. They won the giant building game. But at what cost?

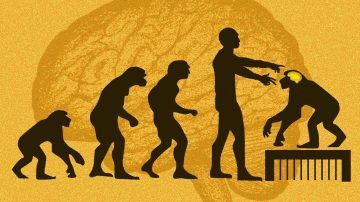

A creature that does perceive the external world to any significant degree can be called a conscious being. Could there be conscious beings other than those of earth’s animal kingdom? Perhaps there are some outside our solar system. Could a robot be a conscious being, just in this modest sense of perceiving its environment? I don’t see why not. Despite appearances, a robot can amass information through its sensors and build a representation of the external world. Granted, there are plenty of arguments purporting to show that no mere robot could be conscious in any much stronger sense.

A creature that does perceive the external world to any significant degree can be called a conscious being. Could there be conscious beings other than those of earth’s animal kingdom? Perhaps there are some outside our solar system. Could a robot be a conscious being, just in this modest sense of perceiving its environment? I don’t see why not. Despite appearances, a robot can amass information through its sensors and build a representation of the external world. Granted, there are plenty of arguments purporting to show that no mere robot could be conscious in any much stronger sense. Now scientists in southern China report that they’ve tried to narrow the evolutionary gap, creating several transgenic macaque monkeys with extra copies of a human gene suspected of playing a role in shaping human intelligence.

Now scientists in southern China report that they’ve tried to narrow the evolutionary gap, creating several transgenic macaque monkeys with extra copies of a human gene suspected of playing a role in shaping human intelligence. The space age officially began in 1957 with the launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite. But recent years have seen the beginning of a boom in the number of objects orbiting Earth, as satellite tracking and communications have assumed enormous importance in the modern world. This raises obvious concerns for the control and eventual fate of these orbiting artifacts. Natalya Bailey is pioneering a novel approach to satellite propulsion, building tiny ion engines at her company Accion Systems. We talk about how satellite technology is rapidly changing, and what that means for the future of space travel inside and outside the Solar System.

The space age officially began in 1957 with the launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite. But recent years have seen the beginning of a boom in the number of objects orbiting Earth, as satellite tracking and communications have assumed enormous importance in the modern world. This raises obvious concerns for the control and eventual fate of these orbiting artifacts. Natalya Bailey is pioneering a novel approach to satellite propulsion, building tiny ion engines at her company Accion Systems. We talk about how satellite technology is rapidly changing, and what that means for the future of space travel inside and outside the Solar System. ‘The problem

‘The problem Bernie is in

Bernie is in When Brenda Hurwood was in her thirties, she had an accident that left her with a partial disability: She worked in home care support with elderly patients, and she injured her shoulder and neck while helping a client get out of a chair. The injury left her with decreased stamina and constant pain, Hurwood says, and she found it difficult to continue working. “It eroded away my self-confidence as a person,” she says. Hurwood, 63, who lives in Nova Scotia, Canada, says she developed generalized anxiety disorder, which persisted for decades. She tried different forms of therapy and various medications, but nothing worked — until 15 years ago, when a therapist introduced her to acceptance and commitment therapy.

When Brenda Hurwood was in her thirties, she had an accident that left her with a partial disability: She worked in home care support with elderly patients, and she injured her shoulder and neck while helping a client get out of a chair. The injury left her with decreased stamina and constant pain, Hurwood says, and she found it difficult to continue working. “It eroded away my self-confidence as a person,” she says. Hurwood, 63, who lives in Nova Scotia, Canada, says she developed generalized anxiety disorder, which persisted for decades. She tried different forms of therapy and various medications, but nothing worked — until 15 years ago, when a therapist introduced her to acceptance and commitment therapy. As the

As the  For many writers, Sam Lipsyte’s readerly eyes are the most coveted. Hordes flock to the Columbia MFA Writing Program for the chance to take his fiction workshop, where he and I first met. On campus, revved up egos struggled under the weight of our grandiose dreams. We students all crossed our fingers in hopes that we’d be one of the lucky ones to gain access to The Great Lipsyte’s secrets.

For many writers, Sam Lipsyte’s readerly eyes are the most coveted. Hordes flock to the Columbia MFA Writing Program for the chance to take his fiction workshop, where he and I first met. On campus, revved up egos struggled under the weight of our grandiose dreams. We students all crossed our fingers in hopes that we’d be one of the lucky ones to gain access to The Great Lipsyte’s secrets.