James Meadway in Novara Media:

James Meadway in Novara Media:

New research from US business think tank Conference Board shows that the rush into the digital economy is doing nothing for capitalism’s global woes.

Far from spurring the system to greater and greater heights, digital technology seems to be having no impact on the growth in productivity that is crucial to the system’s long-term future. Measured as output per worker, global productivity has risen just 2% a year in the past few years, compared to 2.9% a year in the decade before the 2008 crash. Strikingly, Conference Board reckons almost none of this productivity growth has emerged because new technology has made work more efficient. And with sick man of Europe Britain leading the way, the productivity slowdown here has been worst out of all the so-called ‘advanced economies’.

One traditional culprit for low productivity is low investment, which continues to falter. Business investment in Britain has been falling for some time, but this is about more than just the uncertainty induced by the government’s Brexit failures, since investment is also weak across the advanced economies, including the US and Germany.

As discussed in my previous column, in the place of investment, companies (especially large companies) are hoarding cash at record levels, with British companies holding nearly £700bn unused in their bank accounts, and paying out record amounts to shareholders, often using share buybacks. IMF figures show US corporations making payouts worth 0.9% of their assets to shareholders last year, but making investments worth just 0.7%. At the same time, financial chicanery has become routine for non-financial corporations, with the growth in the use of dubious debt instruments like collateralised loan obligations piggybacking the wider expansion of corporate debt.

More here.

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman in The National Interest:

Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman in The National Interest: Francisco Goldman in the NYT:

Francisco Goldman in the NYT: Nathan Robinson in Current Affairs:

Nathan Robinson in Current Affairs: T

T CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose.

CAN POEMS TEACH US how to live? What does it mean to approach poetry as a source of self-help? It’s not hard to call to mind examples of poetry that rouse or soothe or refocus a reader, lifting or quieting the mind like a deep breath. Yet much of the poetry encountered in literature classrooms and canonical anthologies may not readily reflect the self that is reading it, and therefore may not readily become a tool of self-improvement. The work of many modernist poets in particular is placed under the banner of “art for art’s sake,” a motto meant to explicitly free such poetry from the responsibility of serving a didactic or utilitarian function. The poems of Wallace Stevens, for instance, are frequently taken to epitomize the kind of high modernist difficulty that in its slippery symbology and ambiguous affect would seemingly resist being reliably employed for any useful purpose. W

W There is a scene toward the end of Ian McEwan’s new novel, Machines Like Me, when the narrator, Charlie, is pushing his lifelike prototype robot, Adam, in a wheelchair through a demonstration in Trafalgar Square. The demonstrators are protesting about everything under the sun – “poverty, unemployment, housing, healthcare, education, crime, race, gender, climate, opportunity”. The suggestion being presented by McEwan and his narrator, however, is that here, unnoticed in their midst, is the one thing they should be most concerned about: a man-made intelligence greater than their own. There is a Cassandra tendency in McEwan’s fiction. His domestic dramas routinely play out against a backdrop of threatened doom. Since the portent-laden meditation on war and terrorism,

There is a scene toward the end of Ian McEwan’s new novel, Machines Like Me, when the narrator, Charlie, is pushing his lifelike prototype robot, Adam, in a wheelchair through a demonstration in Trafalgar Square. The demonstrators are protesting about everything under the sun – “poverty, unemployment, housing, healthcare, education, crime, race, gender, climate, opportunity”. The suggestion being presented by McEwan and his narrator, however, is that here, unnoticed in their midst, is the one thing they should be most concerned about: a man-made intelligence greater than their own. There is a Cassandra tendency in McEwan’s fiction. His domestic dramas routinely play out against a backdrop of threatened doom. Since the portent-laden meditation on war and terrorism,  In 1956, Sergio D’Angelo made a journey by train from Moscow southwest to the Soviet-made writers’ colony Peredelkino. He was there to meet the rock-star famous writer Boris Pasternak, whose poetry was so beloved that, if he paused during a reading, audiences would shout the missing words. But Pasternak’s original work hadn’t seen daylight in years; the Soviet government didn’t possess quite the same warm feeling toward Pasternak as his fans, doubting his loyalty to the Communist Party, which controlled the publishing industry. He’d been translating classic works of literature, such as Shakespeare’s plays, into Russian instead since the 1940s.

In 1956, Sergio D’Angelo made a journey by train from Moscow southwest to the Soviet-made writers’ colony Peredelkino. He was there to meet the rock-star famous writer Boris Pasternak, whose poetry was so beloved that, if he paused during a reading, audiences would shout the missing words. But Pasternak’s original work hadn’t seen daylight in years; the Soviet government didn’t possess quite the same warm feeling toward Pasternak as his fans, doubting his loyalty to the Communist Party, which controlled the publishing industry. He’d been translating classic works of literature, such as Shakespeare’s plays, into Russian instead since the 1940s. In just over an hour, a

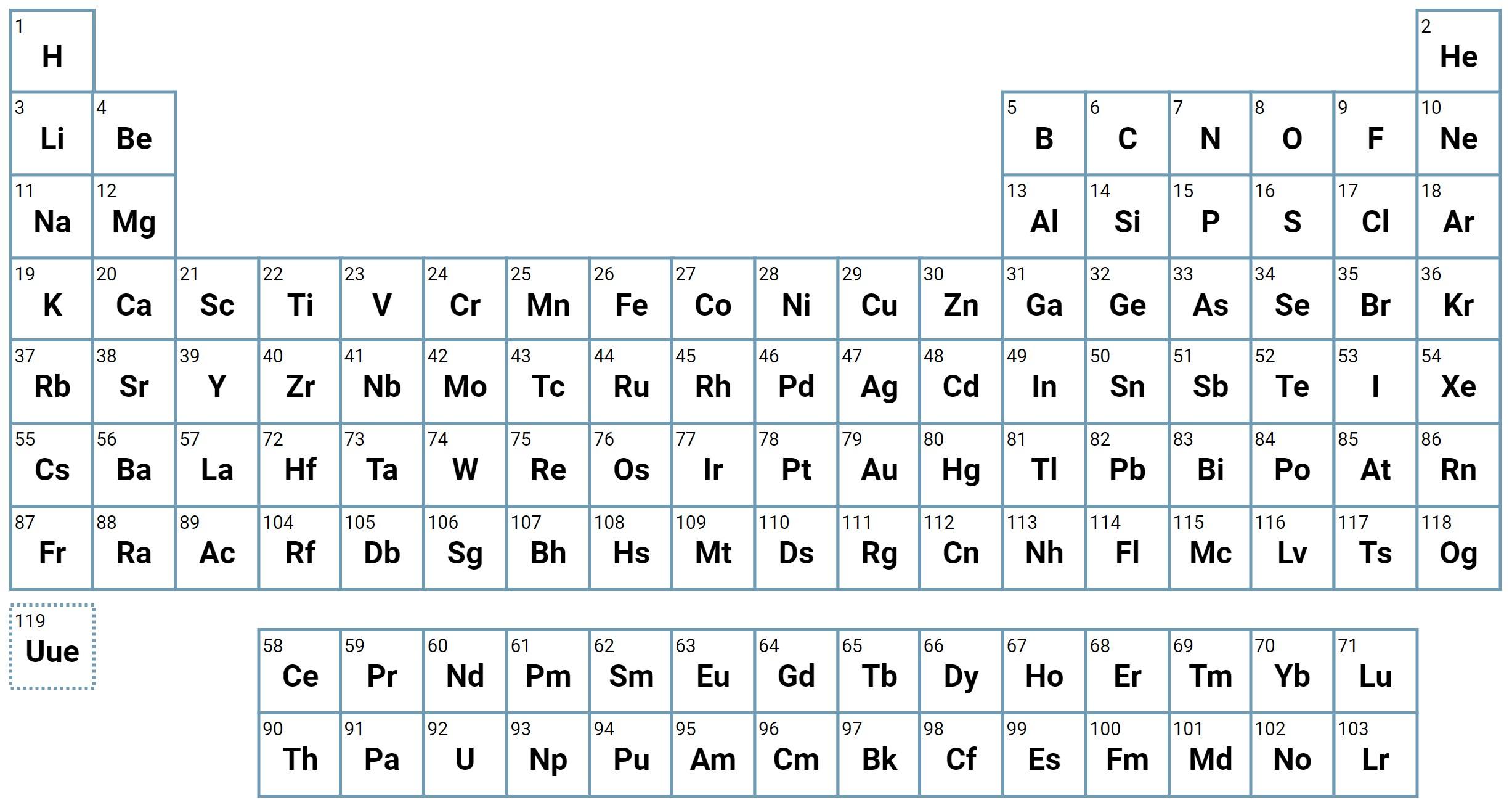

In just over an hour, a  A review of the Periodic Table composed of 119 science haiku, one for each element, plus a closing haiku for element 119 (not yet synthesized). The haiku encompass astronomy, biology, chemistry, history, physics, and a bit of whimsical flair. Click or hover over an element on the Periodic Table to read the haiku.

A review of the Periodic Table composed of 119 science haiku, one for each element, plus a closing haiku for element 119 (not yet synthesized). The haiku encompass astronomy, biology, chemistry, history, physics, and a bit of whimsical flair. Click or hover over an element on the Periodic Table to read the haiku. Israel’s legislative elections on 9 April were a tribute to Binyamin Netanyahu’s transformation of the political landscape. At no point were they discussed in terms of which candidates might be persuaded by (non-existent) American pressure, or the ‘international community’, to end the occupation. This time it was a question of which party leader could be trusted by Israeli Jews – Palestinian citizens of Israel are now officially second-class – to manage the occupation, and to expedite the various tasks that the Jewish state has mastered: killing Gazans, bulldozing homes, combatting the scourge of BDS, and conflating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. With his promise to annex the West Bank, Netanyahu had won even before the election was held. It wasn’t simply Trump’s recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights that sped the incumbent on his way; it was the nature of the conversation – and the fact that the leader of the opposition was Benny Gantz, the IDF commander who presided over the 2014 ‘Operation Protection Edge’, in which more than 2000 Gazans were killed.

Israel’s legislative elections on 9 April were a tribute to Binyamin Netanyahu’s transformation of the political landscape. At no point were they discussed in terms of which candidates might be persuaded by (non-existent) American pressure, or the ‘international community’, to end the occupation. This time it was a question of which party leader could be trusted by Israeli Jews – Palestinian citizens of Israel are now officially second-class – to manage the occupation, and to expedite the various tasks that the Jewish state has mastered: killing Gazans, bulldozing homes, combatting the scourge of BDS, and conflating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism. With his promise to annex the West Bank, Netanyahu had won even before the election was held. It wasn’t simply Trump’s recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights that sped the incumbent on his way; it was the nature of the conversation – and the fact that the leader of the opposition was Benny Gantz, the IDF commander who presided over the 2014 ‘Operation Protection Edge’, in which more than 2000 Gazans were killed. This winter, members of the National Rifle Association—elk hunters in Montana, skeet shooters in upstate New York, concealed-carry enthusiasts in Jacksonville—might have noticed a desperate tone in the organization’s fund-raising efforts. In a letter from early March, Wayne LaPierre, the N.R.A.’s top executive, warned that liberal regulators were threatening to destroy the organization. “We’re facing an attack that’s unprecedented not just in the history of the N.R.A. but in the entire history of our country,” he wrote. “The Second Amendment cannot survive without the N.R.A., and the N.R.A. cannot survive without your help right now.”

This winter, members of the National Rifle Association—elk hunters in Montana, skeet shooters in upstate New York, concealed-carry enthusiasts in Jacksonville—might have noticed a desperate tone in the organization’s fund-raising efforts. In a letter from early March, Wayne LaPierre, the N.R.A.’s top executive, warned that liberal regulators were threatening to destroy the organization. “We’re facing an attack that’s unprecedented not just in the history of the N.R.A. but in the entire history of our country,” he wrote. “The Second Amendment cannot survive without the N.R.A., and the N.R.A. cannot survive without your help right now.” The human gut harbors trillions of invisible microbial inhabitants, referred to as the microbiota, that collectively produce thousands of unique small molecules. The sources and biological functions of the vast majority of these molecules are unknown. Yale researchers recently applied a new technology to uncover microbiota-derived chemicals that affect human physiology, revealing a complex network of interactions with potentially broad-reaching impacts on human health.

The human gut harbors trillions of invisible microbial inhabitants, referred to as the microbiota, that collectively produce thousands of unique small molecules. The sources and biological functions of the vast majority of these molecules are unknown. Yale researchers recently applied a new technology to uncover microbiota-derived chemicals that affect human physiology, revealing a complex network of interactions with potentially broad-reaching impacts on human health. At 3 p.m. on a Monday afternoon, death announced it was coming for him. He was only eight years old; his cancer cells were not responding to treatment anymore. His body’s leukemic blast cell counts were doubling daily. Bone marrow was no longer making red or white blood cells, not even platelets. The marrow was only churning out cancer cells. In a process similar to churning butter, his blood was thickening with homogenous, malicious content: cancer. And like churning butter, it was exhausting work. The battered remnants of his healthy self were beaten down by chemo. And yet, every fiber pressed on.

At 3 p.m. on a Monday afternoon, death announced it was coming for him. He was only eight years old; his cancer cells were not responding to treatment anymore. His body’s leukemic blast cell counts were doubling daily. Bone marrow was no longer making red or white blood cells, not even platelets. The marrow was only churning out cancer cells. In a process similar to churning butter, his blood was thickening with homogenous, malicious content: cancer. And like churning butter, it was exhausting work. The battered remnants of his healthy self were beaten down by chemo. And yet, every fiber pressed on.

As Nicholas Money puts it in Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History, thinking of the mushroom in place of the whole mushroom-forming organism is ‘a bit like using a photograph of a large pair of testicles to represent an elephant’. (The flaw in this memorable comparison is that the spore inside a mushroom is ready to grow into next-generation fungus, so long as it’s launched into congenial conditions, whereas an elephant sperm cell only contains half the chromosomes needed to begin a baby elephant.) Like the testicle, the mushroom is just one component of an organism, relatively peripheral to the organism’s viability, if essential to the continuation of its species. Unlike the elephant testicle (and hence the force of Money’s comparison), it is the part of the organism to which human cultures have in general paid the most attention. It’s this spore-disperser, not the hard-working mycelium, that we might consider dining on, illustrating, ingesting for hallucinatory or medicinal purposes, founding a taxonomic system around, deploying in the assassination of an unlikeable Roman emperor, or photographing on our nature rambles. It’s what appears in the field guides, the cookbooks, and the mythologies.

As Nicholas Money puts it in Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History, thinking of the mushroom in place of the whole mushroom-forming organism is ‘a bit like using a photograph of a large pair of testicles to represent an elephant’. (The flaw in this memorable comparison is that the spore inside a mushroom is ready to grow into next-generation fungus, so long as it’s launched into congenial conditions, whereas an elephant sperm cell only contains half the chromosomes needed to begin a baby elephant.) Like the testicle, the mushroom is just one component of an organism, relatively peripheral to the organism’s viability, if essential to the continuation of its species. Unlike the elephant testicle (and hence the force of Money’s comparison), it is the part of the organism to which human cultures have in general paid the most attention. It’s this spore-disperser, not the hard-working mycelium, that we might consider dining on, illustrating, ingesting for hallucinatory or medicinal purposes, founding a taxonomic system around, deploying in the assassination of an unlikeable Roman emperor, or photographing on our nature rambles. It’s what appears in the field guides, the cookbooks, and the mythologies.