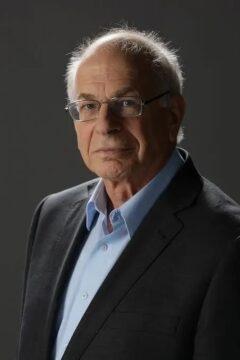

Gerd Gigerenzer in Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics:

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s joint papers from the 1970s and 1980s have inspired many, including myself. These articles magically turned statistical thinking—previously a niche interest—into a major re-search focus. Kahneman and Tversky revived the concept of heuristics, which had largely been forgotten at the time, and played a pivotal role in bringing psychology to the attention of economics and other social sciences. I was also deeply influenced by Tversky’s seminal work on the foundations of measurement, which inspired my first book on modeling.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s joint papers from the 1970s and 1980s have inspired many, including myself. These articles magically turned statistical thinking—previously a niche interest—into a major re-search focus. Kahneman and Tversky revived the concept of heuristics, which had largely been forgotten at the time, and played a pivotal role in bringing psychology to the attention of economics and other social sciences. I was also deeply influenced by Tversky’s seminal work on the foundations of measurement, which inspired my first book on modeling.

In their joint work, known as the heuristics-and-biases program, Kahneman and Tversky argued that human judgment systematically deviates from the norms of probability and logic, resulting in predictable cognitive biases. These biases were attributed to heuristics—mental shortcuts—which led to a broader narrative in behavioral economics and psychology that emphasized human fallibility in decision-making.

The heuristics-and-biases program sparked intense debate on the nature of human rationality. This debate placed me in direct opposition to Kahneman and Tversky, with Kahneman referring to me in Thinking, Fast and Slow as “our most persistent critic”.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Jan. 28, 2026, President Donald Trump sharply intensified his threats to the Islamic Republic, suggesting that if Tehran did not agree to a set of demands, he could mount an attack “

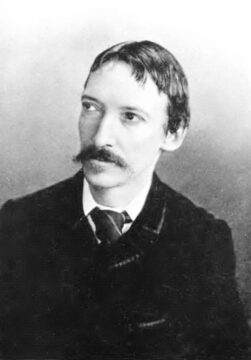

On Jan. 28, 2026, President Donald Trump sharply intensified his threats to the Islamic Republic, suggesting that if Tehran did not agree to a set of demands, he could mount an attack “ The adventure story and the historical romance were two genres at which Stevenson excelled, but he was also brilliant at the macabre psychological parable in his novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and the supernatural in his short story “Thrawn Janet” (1881). The first of these takes on the very “fortress of identity” (in Jekyll’s words) that has so obsessed us of late but turns it into something timeless. Damrosch tells us that the novella caused a furious argument between Stevenson and his wife, in which she comes off better than he does. When Louis read aloud his first draft, as Fanny’s son Lloyd recalled, “Her praise was constrained; the words seemed to come with difficulty; and then all at once she broke out with criticism. He had missed the point, she said; had missed the allegory; had made it merely a story—a magnificent bit of sensationalism—when it should have been a masterpiece.” Damrosch continues, “Fanny’s point was that Louis had ruined the story by turning it into a mere tale about a secret life. . . . What was needed was not just a character wearing a disguise, but something far more profound: a character struggling with a deeper hidden self that breaks loose and fights for supremacy.” Louis resisted, then came around, went back to work, and gave her the masterpiece she wanted. Thereafter, he jokingly referred to her as “the critic on the hearth.”

The adventure story and the historical romance were two genres at which Stevenson excelled, but he was also brilliant at the macabre psychological parable in his novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and the supernatural in his short story “Thrawn Janet” (1881). The first of these takes on the very “fortress of identity” (in Jekyll’s words) that has so obsessed us of late but turns it into something timeless. Damrosch tells us that the novella caused a furious argument between Stevenson and his wife, in which she comes off better than he does. When Louis read aloud his first draft, as Fanny’s son Lloyd recalled, “Her praise was constrained; the words seemed to come with difficulty; and then all at once she broke out with criticism. He had missed the point, she said; had missed the allegory; had made it merely a story—a magnificent bit of sensationalism—when it should have been a masterpiece.” Damrosch continues, “Fanny’s point was that Louis had ruined the story by turning it into a mere tale about a secret life. . . . What was needed was not just a character wearing a disguise, but something far more profound: a character struggling with a deeper hidden self that breaks loose and fights for supremacy.” Louis resisted, then came around, went back to work, and gave her the masterpiece she wanted. Thereafter, he jokingly referred to her as “the critic on the hearth.” Popular wisdom holds we can ‘rewire’ our brains: after a stroke, after trauma, after learning a new skill, even with

Popular wisdom holds we can ‘rewire’ our brains: after a stroke, after trauma, after learning a new skill, even with  Creativity is a trait that AI critics say is likely to remain the preserve of humans for the foreseeable future. But a large-scale study finds that leading generative language models can now exceed the average human performance on linguistic creativity tests.

Creativity is a trait that AI critics say is likely to remain the preserve of humans for the foreseeable future. But a large-scale study finds that leading generative language models can now exceed the average human performance on linguistic creativity tests. So I was thinking about the old logic problem/koan

So I was thinking about the old logic problem/koan Dr Johnson never filmed a “spicy books with cartoon covers” vlog. But Jack Edwards cannot quite deny being the most important literary critic in the world. In commercial terms, he certainly is. A nod from him fills bathtubs, train carriages and public parks with copies of a book he likes. Booksellers buy and arrange their stock to his taste. And he is not confined to new releases. When he dug up an obscure Dostoevsky (White Nights), his positive review moved it from cellars to shop windows instantaneously. I first met him for this interview around the time of the 2024 International Booker Prize. He had been asked to host the ceremony – and to livestream it. I watched him cruise up the red carpet, encircled by cameras and attendants.

Dr Johnson never filmed a “spicy books with cartoon covers” vlog. But Jack Edwards cannot quite deny being the most important literary critic in the world. In commercial terms, he certainly is. A nod from him fills bathtubs, train carriages and public parks with copies of a book he likes. Booksellers buy and arrange their stock to his taste. And he is not confined to new releases. When he dug up an obscure Dostoevsky (White Nights), his positive review moved it from cellars to shop windows instantaneously. I first met him for this interview around the time of the 2024 International Booker Prize. He had been asked to host the ceremony – and to livestream it. I watched him cruise up the red carpet, encircled by cameras and attendants. The backstory: a few months ago, Anthropic released Claude Code, an exceptionally productive programming agent. A few weeks ago, a user modified it into Clawdbot, a generalized lobster-themed AI personal assistant. It’s free, open-source, and “empowered” in the corporate sense – the designer

The backstory: a few months ago, Anthropic released Claude Code, an exceptionally productive programming agent. A few weeks ago, a user modified it into Clawdbot, a generalized lobster-themed AI personal assistant. It’s free, open-source, and “empowered” in the corporate sense – the designer  Political hypocrisy is usually treated as a moral failure—a sign that rulers invoke law and principle only when convenient. Yet this familiar condemnation misses a more unsettling possibility: that hypocrisy has also played a constitutive role in modern political life. By forcing power to justify itself, even dishonestly, it compelled rulers to speak a language they did not fully control. This insistence on explanation was never merely decorative. Power was expected to render itself intelligible, to offer reasons that could be contested or rejected. Hypocrisy preserved this expectation even as it betrayed it. By invoking principles it did not honor, power acknowledged their authority, keeping open the space for judgment, critique, and resistance.

Political hypocrisy is usually treated as a moral failure—a sign that rulers invoke law and principle only when convenient. Yet this familiar condemnation misses a more unsettling possibility: that hypocrisy has also played a constitutive role in modern political life. By forcing power to justify itself, even dishonestly, it compelled rulers to speak a language they did not fully control. This insistence on explanation was never merely decorative. Power was expected to render itself intelligible, to offer reasons that could be contested or rejected. Hypocrisy preserved this expectation even as it betrayed it. By invoking principles it did not honor, power acknowledged their authority, keeping open the space for judgment, critique, and resistance. The file is called SOUL.md. It sits in a folder on whatever machine an AI agent calls home. A Mac Mini in someone’s apartment, a cloud server, a Raspberry Pi in a closet. The file contains instructions: who the agent is, how it should behave, what it values. Every time the agent wakes up, it reads SOUL.md first. Before checking email, before browsing the web, before doing anything at all, it reads itself into being.

The file is called SOUL.md. It sits in a folder on whatever machine an AI agent calls home. A Mac Mini in someone’s apartment, a cloud server, a Raspberry Pi in a closet. The file contains instructions: who the agent is, how it should behave, what it values. Every time the agent wakes up, it reads SOUL.md first. Before checking email, before browsing the web, before doing anything at all, it reads itself into being. Charlie Chaplin (1889–1977) gets top billing in the subtitle of Hard Streets but he’s not the star of the show. The book begins with and is built around an earlier rags-to-riches tale and its wider purpose is to make us look closer at the rags and be less beguiled by the riches.

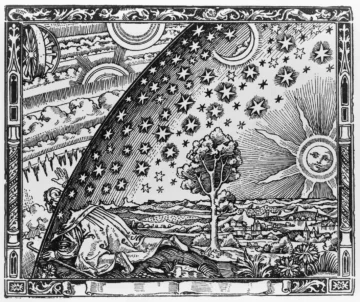

Charlie Chaplin (1889–1977) gets top billing in the subtitle of Hard Streets but he’s not the star of the show. The book begins with and is built around an earlier rags-to-riches tale and its wider purpose is to make us look closer at the rags and be less beguiled by the riches. Puffed-up Sun. Data from inside the Sun’s corona — the outermost layer of its atmosphere — helped astrophysicists to create a sharper picture of the Sun’s shifting boundaries than ever before. The corona’s outer edge, depicted in this illustration, has a rough, spiky shape that expands and contracts like a pufferfish as the Sun becomes more or less active.

Puffed-up Sun. Data from inside the Sun’s corona — the outermost layer of its atmosphere — helped astrophysicists to create a sharper picture of the Sun’s shifting boundaries than ever before. The corona’s outer edge, depicted in this illustration, has a rough, spiky shape that expands and contracts like a pufferfish as the Sun becomes more or less active.