Lisa Allardice in The Guardian:

At a PEN lecture in Manhattan last weekend, the novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie took Hillary Clinton to task for beginning her Twitter biowith “Wife, mom, grandma”. Her husband’s account, it will surprise no one to know, does not begin with the word “husband”. “When you put it like that, I’m going to change it,” promised the 2016 presidential candidate. Adichie is an international bestseller and about as starry as a writer can be (when we meet she chats casually about recently meeting Oprah Winfrey, who made a little bow to her). Her first novel, Purple Hibiscus, published when she was only 26, was longlisted for the 2004 Man Booker; she won the 2006 Orange prize for Half of a Yellow Sun; was awarded a MacArthur fellowship – the so-called genius grant – and her work is now a fixture on American school reading lists. Following her sensational 2013 TED talk, We Should All Be Feminists, (sampled by Beyoncé, used by Dior for a series of slogan T-shirts and distributed in book format to every 16-year-old in Sweden) the 40-year-old has become something of a public feminist: hence scolding the former US secretary of state.

The atmosphere at a recent event with Reni Eddo-Lodge (author of Why I Am No Longer Talking to White People About Race), part of the Southbank’s WOW: Women of the World festival in London, was more like a party than a books evening. The excitement among the audience of largely young women was as striking as the amazing hair and outfits (“That will be the Nigerians,” Adichie says proudly). The two writers received a riotous standing ovation before they had even sat down. As festival founder Jude Kelly said in her whoop-inducing introduction, “The world is changing very fast, and we intend to accelerate it.”

…But now in Dear Ijeawele: A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions (just published in paperback), she writes that she is angrier about sexism than she is about racism. “I don’t think sexism is worse than racism, it’s impossible even to compare,” she clarifies. “It’s that I feel lonely in my fight against sexism, in a way that I don’t feel in my fight against racism. My friends, my family, they get racism, they get it. The people I’m close to who are not black get it. But I find that with sexism you are constantly having to explain, justify, convince, make a case for.” Written just before the birth of her own daughter, the manifesto began as a letter to her friend, who had asked for advice about how she might raise her baby girl as a feminist. “Teach her to love books”; “it is important to be able to fend for herself”.

More here.

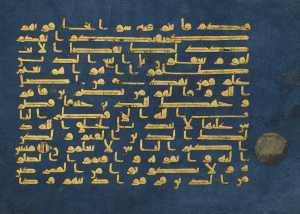

What is shariʿa? It is often translated as “Islamic law,” as if it represented the law in its entirety. It is also commonly thought to be a rigid set of practices and punishments inherited directly from early Islam that are meant to be applied in a single inflexible manner. But none of this is accurate.

What is shariʿa? It is often translated as “Islamic law,” as if it represented the law in its entirety. It is also commonly thought to be a rigid set of practices and punishments inherited directly from early Islam that are meant to be applied in a single inflexible manner. But none of this is accurate.