Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New York Times:

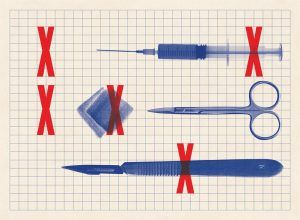

Late last year, I witnessed an extraordinary surgical procedure at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The patient was a middle-aged man who was born with a leaky valve at the root of his aorta, the wide-bored blood vessel that arcs out of the human heart and carries blood to the upper and lower reaches of the body. That faulty valve had been replaced several years ago but wasn’t working properly and was leaking again. To fix the valve, the cardiac surgeon intended to remove the old tissue, resecting the ring-shaped wall of the aorta around it. He would then build a new vessel wall, crafted from the heart-lining of a cow, and stitch a new valve into that freshly built ring of aorta. It was the most exquisite form of human tailoring that I had ever seen. The surgical suite ran with unobstructed, preternatural smoothness. Minutes before the incision was made, the charge nurse called a “time out.” The patient’s identity was confirmed by the name tag on his wrist. The surgeon reviewed the anatomy, while the nurses — six in all — took their positions around the bed and identified themselves by name. A large steel tray, with needles, sponges, gauze and scalpels, was placed in front of the head nurse. Each time a scalpel or sponge was removed from the tray, as I recall, the nurse checked off a box on a list; when it was returned, the box was checked off again. The old tray was not exchanged for a new one, I noted, until every item had been ticked off twice. It was a simple, effective method to stave off a devastating but avoidable human error: leaving a needle or sponge inside a patient’s body.

Late last year, I witnessed an extraordinary surgical procedure at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The patient was a middle-aged man who was born with a leaky valve at the root of his aorta, the wide-bored blood vessel that arcs out of the human heart and carries blood to the upper and lower reaches of the body. That faulty valve had been replaced several years ago but wasn’t working properly and was leaking again. To fix the valve, the cardiac surgeon intended to remove the old tissue, resecting the ring-shaped wall of the aorta around it. He would then build a new vessel wall, crafted from the heart-lining of a cow, and stitch a new valve into that freshly built ring of aorta. It was the most exquisite form of human tailoring that I had ever seen. The surgical suite ran with unobstructed, preternatural smoothness. Minutes before the incision was made, the charge nurse called a “time out.” The patient’s identity was confirmed by the name tag on his wrist. The surgeon reviewed the anatomy, while the nurses — six in all — took their positions around the bed and identified themselves by name. A large steel tray, with needles, sponges, gauze and scalpels, was placed in front of the head nurse. Each time a scalpel or sponge was removed from the tray, as I recall, the nurse checked off a box on a list; when it was returned, the box was checked off again. The old tray was not exchanged for a new one, I noted, until every item had been ticked off twice. It was a simple, effective method to stave off a devastating but avoidable human error: leaving a needle or sponge inside a patient’s body.

In 2007, the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande began a study to determine whether a 19-item “checklist” might reduce human errors during surgery. The items on the list included many of the checks that I had seen in action in the operating room: the verification of a patient’s name and the surgical site before incision; documentation of any previous allergic reactions; confirmation that blood and fluids would be at hand if needed; and, of course, a protocol to account for every needle and tool before and after a surgical procedure. Gawande’s team applied this checklist to eight sites in eight cities across the globe, including hospitals in India, Canada, Tanzania and the United States, and measured the rate of death and complications before and after implementation.

The results were startling: The mortality rate fell to 0.8 percent from 1.5 percent, and surgical complications declined to 7 percent from 11 percent.

More here.

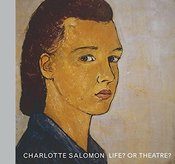

Origin stories are woven with many threads: Some we spin ourselves, while others we inherit. The great German artist Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943) accounted for herself—for who she was, and why she was, and where she came from—not by wondering what of herself was fact and what was fiction. Rather, the real and present question was Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?). In other words, how to distinguish genuine presence and raw experience from the spectacle and folly of human making.

Origin stories are woven with many threads: Some we spin ourselves, while others we inherit. The great German artist Charlotte Salomon (1917–1943) accounted for herself—for who she was, and why she was, and where she came from—not by wondering what of herself was fact and what was fiction. Rather, the real and present question was Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?). In other words, how to distinguish genuine presence and raw experience from the spectacle and folly of human making. There’s

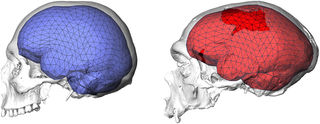

There’s In recent months, there’s been a groundswell of evidence showing that more volume in both the left and right hemispheres of the cerebellum (Latin for “little

In recent months, there’s been a groundswell of evidence showing that more volume in both the left and right hemispheres of the cerebellum (Latin for “little  One hundred and sixty years ago, at a time when the light bulb was not yet invented, Karl Marx predicted that robots would replace humans in the workplace.

One hundred and sixty years ago, at a time when the light bulb was not yet invented, Karl Marx predicted that robots would replace humans in the workplace. Politics on both sides of the Atlantic is being played out in the costumes of dead generations. Trump won the White House with a Reagan campaign slogan, pledging to bring back factory jobs and tariff wars. Democrats believe desperately in the existence of Russian conspiracies. British conservatives yearn for the nineteenth century, while academics at Oxford seek an “intelligent Christian ethic of empire.” Jeremy Corbyn has made postwar socialism popular again, with the help of a line from Shelley. Such retromania might not be so surprising—every age of crisis, as Marx famously argued, conjures up the spirits of the past for guidance and inspiration. But it is harder to account for a ghostly presence that provides neither: the public intellectual who wants to fight about the Enlightenment.

Politics on both sides of the Atlantic is being played out in the costumes of dead generations. Trump won the White House with a Reagan campaign slogan, pledging to bring back factory jobs and tariff wars. Democrats believe desperately in the existence of Russian conspiracies. British conservatives yearn for the nineteenth century, while academics at Oxford seek an “intelligent Christian ethic of empire.” Jeremy Corbyn has made postwar socialism popular again, with the help of a line from Shelley. Such retromania might not be so surprising—every age of crisis, as Marx famously argued, conjures up the spirits of the past for guidance and inspiration. But it is harder to account for a ghostly presence that provides neither: the public intellectual who wants to fight about the Enlightenment.

O

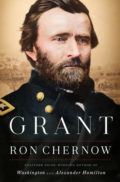

O Grant was thirty-nine years old, apparently a hopeless failure, when Confederate troops fired the first shots on Fort Sumter. In the meantime, his political ideas had been slowly developing. While Jesse Grant was an avid abolitionist, Ulysses was no such thing; he opposed slavery in theory, but also feared, like many Northerners, that “outright abolitionism might lead to bloody sectional conflict.” He had even cast his one vote in a presidential election for James Buchanan, a Democrat—a fact that would embarrass him in later years. His father-in-law Fred Dent (a man as bossy and controlling as his own father) was a Missouri slaveowner of reactionary leanings, and his own wife, Julia, owned slaves while she was married to Grant, not divesting herself of this property until the Emancipation Proclamation. Grant himself quickly freed the slave who was given him by Fred, William Jones, but he was no abolitionist, dismissing John Brown’s raid as the act of a fanatic. But Chernow provides evidence that Grant became increasingly anti-slavery, a Free-Soil Democrat, in the years leading up to the war.

Grant was thirty-nine years old, apparently a hopeless failure, when Confederate troops fired the first shots on Fort Sumter. In the meantime, his political ideas had been slowly developing. While Jesse Grant was an avid abolitionist, Ulysses was no such thing; he opposed slavery in theory, but also feared, like many Northerners, that “outright abolitionism might lead to bloody sectional conflict.” He had even cast his one vote in a presidential election for James Buchanan, a Democrat—a fact that would embarrass him in later years. His father-in-law Fred Dent (a man as bossy and controlling as his own father) was a Missouri slaveowner of reactionary leanings, and his own wife, Julia, owned slaves while she was married to Grant, not divesting herself of this property until the Emancipation Proclamation. Grant himself quickly freed the slave who was given him by Fred, William Jones, but he was no abolitionist, dismissing John Brown’s raid as the act of a fanatic. But Chernow provides evidence that Grant became increasingly anti-slavery, a Free-Soil Democrat, in the years leading up to the war. As humans, we are defined by, among other things, our desire to transcend our humanity. Mythology, religion, fiction and science offer different versions of this dream. Transhumanism – a social movement predicated on the belief that we can and should leave behind our biological condition by merging with technology – is a kind of feverish amalgamation of all four. Though it’s oriented toward the future, and is fuelled by excitable speculation about the implications of the latest science and technology, its roots can be glimpsed in ancient stories like that of the Sumerian king Gilgamesh and his quest for immortality.

As humans, we are defined by, among other things, our desire to transcend our humanity. Mythology, religion, fiction and science offer different versions of this dream. Transhumanism – a social movement predicated on the belief that we can and should leave behind our biological condition by merging with technology – is a kind of feverish amalgamation of all four. Though it’s oriented toward the future, and is fuelled by excitable speculation about the implications of the latest science and technology, its roots can be glimpsed in ancient stories like that of the Sumerian king Gilgamesh and his quest for immortality. According to Akeel Bilgrami, liberalism and liberal politics have their own limitations and cannot save us from the savagery of capital. In this way, he intellectually provokes us to go beyond liberalism and reimagine an alternative political vocabulary. His philosophy rejects the ideology of capitalism and envisions an alternative as the way forward for humanity. This alternative is, of course, Left-centric and socialistic in perspective, and Bilgrami sympathises with the Left politics in his home country and others.

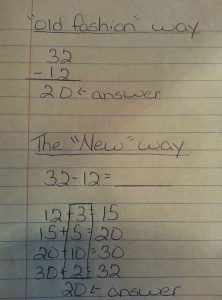

According to Akeel Bilgrami, liberalism and liberal politics have their own limitations and cannot save us from the savagery of capital. In this way, he intellectually provokes us to go beyond liberalism and reimagine an alternative political vocabulary. His philosophy rejects the ideology of capitalism and envisions an alternative as the way forward for humanity. This alternative is, of course, Left-centric and socialistic in perspective, and Bilgrami sympathises with the Left politics in his home country and others. Ever since mathematics got properly underway around 3,000 years ago, there was only one way to achieve access to the field. You had to spend many years developing a fairly extensive calculation skillset. In the first instance, to pass the graduation and entrance examinations to gain initial access to the field. Then, once accepted into the world of mathematics, calculation of one kind or another was what all mathematicians spent the bulk of their mathematical time doing. Arguably, for most of mathematics history, the subject really was, to a large extent, primarily about calculation of one form or another. Newton, Leibniz, Bernoulli (any of them), Fermat, Euler, Riemann, Gauss, and the other greats of times past, were all superb masters of calculation. (We should also include Boole, since his famous Boolean algebra is also a calculation system.)

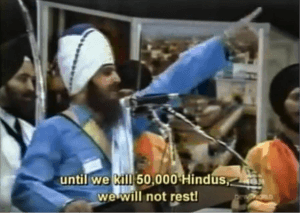

Ever since mathematics got properly underway around 3,000 years ago, there was only one way to achieve access to the field. You had to spend many years developing a fairly extensive calculation skillset. In the first instance, to pass the graduation and entrance examinations to gain initial access to the field. Then, once accepted into the world of mathematics, calculation of one kind or another was what all mathematicians spent the bulk of their mathematical time doing. Arguably, for most of mathematics history, the subject really was, to a large extent, primarily about calculation of one form or another. Newton, Leibniz, Bernoulli (any of them), Fermat, Euler, Riemann, Gauss, and the other greats of times past, were all superb masters of calculation. (We should also include Boole, since his famous Boolean algebra is also a calculation system.) The New York City police officers looked bored, unable to understand a word, as they eyed the angry crowd at Madison Square Garden. A sawmill worker from the Canadian province of British Columbia took the stage with a retinue of robed warriors toting curved swords. He wore an ornate turban and sliced the air with his hand as he promised a massacre of Hindus.

The New York City police officers looked bored, unable to understand a word, as they eyed the angry crowd at Madison Square Garden. A sawmill worker from the Canadian province of British Columbia took the stage with a retinue of robed warriors toting curved swords. He wore an ornate turban and sliced the air with his hand as he promised a massacre of Hindus. It’s 2018 and everybody’s talking about sex robots.

It’s 2018 and everybody’s talking about sex robots. Basingstoke sits roughly equidistant between London, where I’ve lived all my adult life, and Southampton, where I grew up. On the frequent train journey between the two, Southampton would barely ever change, but Basingstoke constantly threw up new office complexes and blocks of luxury flats, seemingly enjoying a permanent boom while Southampton declined. I’d never get off the train to look at the town, having been alarmed by it on a visit as a teenager, by the way there seemed to be “no there there”—just an enclosed mall, ringed by motorways, with Barratt Homes suburbia around it and nothing much more. This, I melodramatically thought to myself, is what they want for all of us, lives lived around shopping, property and nothing else, in towns stripped of anything distinct.

Basingstoke sits roughly equidistant between London, where I’ve lived all my adult life, and Southampton, where I grew up. On the frequent train journey between the two, Southampton would barely ever change, but Basingstoke constantly threw up new office complexes and blocks of luxury flats, seemingly enjoying a permanent boom while Southampton declined. I’d never get off the train to look at the town, having been alarmed by it on a visit as a teenager, by the way there seemed to be “no there there”—just an enclosed mall, ringed by motorways, with Barratt Homes suburbia around it and nothing much more. This, I melodramatically thought to myself, is what they want for all of us, lives lived around shopping, property and nothing else, in towns stripped of anything distinct. Does the lizard brain trick the body into singing its ancient song? Of course, you are more than the parts you recognize as you. Perhaps those other parts were quieter in the past, or did their work without being noticed, while now you can see their elbows, their toes sticking out, pulling on the strings of your life. But those same creatures were always there, pulling on the strings of your life. Will you one day feel about the mothering instinct the same way you now feel about the sex instinct, which also suddenly turned on? Like that other passage, you’ll resist it, but in retrospect, it took you. You didn’t make a choice to go in that direction. Life—nature—pulled your strings. That is why you have no regrets about those years. And where did it land you? In a more interesting place. It resulted in a more interesting time. Is your body now pulling you towards motherhood, in the same way?

Does the lizard brain trick the body into singing its ancient song? Of course, you are more than the parts you recognize as you. Perhaps those other parts were quieter in the past, or did their work without being noticed, while now you can see their elbows, their toes sticking out, pulling on the strings of your life. But those same creatures were always there, pulling on the strings of your life. Will you one day feel about the mothering instinct the same way you now feel about the sex instinct, which also suddenly turned on? Like that other passage, you’ll resist it, but in retrospect, it took you. You didn’t make a choice to go in that direction. Life—nature—pulled your strings. That is why you have no regrets about those years. And where did it land you? In a more interesting place. It resulted in a more interesting time. Is your body now pulling you towards motherhood, in the same way? E

E