Skye C Cleary and Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon:

A strange thing is happening in modern philosophy: many philosophers don’t seem to believe that there is such a thing as human nature. What makes this strange is that, not only does the new attitude run counter to much of the history of philosophy, but – despite loud claims to the contrary – it also goes against the findings of modern science. This has serious consequences, ranging from the way in which we see ourselves and our place in the cosmos to what sort of philosophy of life we might adopt. Our aim here is to discuss the issue of human nature in light of contemporary biology, and then explore how the concept might impact everyday living.

The existence of something like a human nature that separates us from the rest of the animal world has often been implied, and sometimes explicitly stated, throughout the history of philosophy. Aristotle thought that the ‘proper function’ of human beings was to think rationally, from which he derived the idea that the highest life available to us is one of contemplation (ie, philosophising) – hardly unexpected from a philosopher. The Epicureans argued that it is a quintessential aspect of human nature that we are happier when we experience pleasure, and especially when we do not experience pain. Thomas Hobbes believed that we need a strong centralised government to keep us in line because our nature would otherwise lead us to live a life that he memorably characterised as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. Jean-Jacques Rousseau embedded the idea of a human nature in his conception of the ‘noble savage’. Confucius and Mencius thought that human nature is essentially good, while Hsün Tzu considered it essentially evil.

The keyword here is, of course, ‘essentially’. One of the obvious exceptions to this trend was John Locke, who described the human mind as a ‘tabula rasa’ (blank slate), but his take has been rejected by modern science. As one group of cognitive scientists describes it in From Mating to Mentality (2003), our mind is more like a colouring book, or a ‘graffiti-filled wall of a New York subway station’ than a blank slate.

In contrast, many contemporary philosophers, both of the so-called analytic and continental traditions, seem largely to have rejected the very idea of human nature.

More here.

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true.

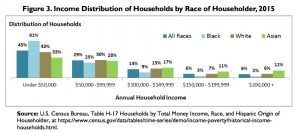

Neuroscientist Michael Heneka knows that radical ideas require convincing data. In 2010, very few colleagues shared his belief that the brain’s immune system has a crucial role in dementia. So in May of that year, when a batch of new results provided the strongest evidence he had yet seen for his theory, he wanted to be excited, but instead felt nervous. He and his team had eliminated a key inflammation gene from a strain of mouse that usually develops symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The modified mice seemed perfectly healthy. They sailed through memory tests and showed barely a sign of the sticky protein plaques that are a hallmark of the disease. Yet Heneka knew that his colleagues would consider the results too good to be true. Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!”

Again, the point is not to highlight the discrepancy between the egalitarian ideals of these students and their class position since, if the equality you’re committed to is between groups, there is no discrepancy. And just as no hypocrisy is required at the elite college where you fight hard against racism, none will be required at the NGO or the job as a consultant or in finance (“Why Goldman Sachs? Diversity!” Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”

Hawkins grew up in a single parent family in Brooklyn and Park Hill on Staten Island. Whenever he inquired about the family patriarch, his mother would reply, “God is your father!” Unlike Mane, who describes being orbited by grandparents, aunts and uncles, Hawkins’s childhood was blighted by black-on-black crime and drugs-related violence. He describes witnessing his first death when he was four years old and watched a woman leap or fall from the roof of an apartment building. “Lovin’ You” by Minnie Riperton was playing on a radio in the street. Hawkins was a member of gangs called Baby Cash Crew, Dick ’Em Down and Wreck Posse. He carried a gun from the ages of 14 to 21 and recalls watching one of his babysitters shooting up heroin on the couch. Years later, Staten Island’s rappers would describe Park Hill as “Killa Hill” in their music. “Dudes would shoot dogs and leave their carcasses behind our building all the time,” writes Hawkins. “It was like a concentration camp for poor black people.”